As an embedded researcher in the Zaatari Syrian refugee camp in Jordan, Karen Fisher wanted to know about the effects of domicide and the invisible lives of women.

Those living in the camp are conservative Sunni Muslim, and it’s rare to see women working in public, said Fisher, a professor at the University of Washington Information School. To learn about women’s daily lives in the camp, she asked many of them to keep and share diaries. When one 15-year-old girl included her favorite cake recipe in hers, it sparked an idea for a way to document women’s knowledge and preserve an important part of Syrian culture.

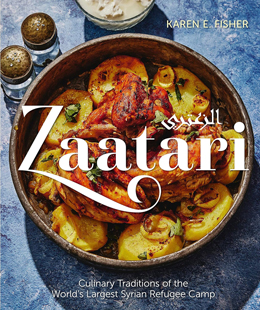

The result, several years in the making, is the book “Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the World's Largest Syrian Refugee Camp,” filled with 130 recipes, along with stories and photos that document the experiences of people living in the camp — home to more than 80,000 people who escaped Syria’s ongoing civil war.

Fisher has worked at Zaatari camp since 2015, three years after the war began. UNHCR (The UN Refugee Agency) provided her the rare opportunity to engage with the Syrians living in the high-security camp. Fisher’s mission there is to preserve Indigenous knowledge, increase global awareness of refugees, facilitate women’s agency, and provide their families with new revenue streams.

When Fisher brought the idea of a cookbook to the UNHCR camp manager, she was surprised to hear an immediate yes. Women in the camp were highly enthusiastic about it too.

“Then they asked, ‘What is a cookbook? What is a recipe?’” Fisher said. “The women had learned to cook from their mothers. Nothing was recorded, and many people have low literacy. If they had a book, it was the family Quran.

“This was very freeing for us, because it left it wide open to think about what comprises a recipe and what a camp book would look like,” Fisher said. It also presented many challenges at every juncture. The women, for example, handwrote their recipes and stories with many omissions, did not use measuring spoons or cups, and had adapted their recipes to the camp environment.

“So much of their cooking knowledge was tacitly known and learned through corporeal, embodied practices,” Fisher said. Working with Hourani Arabic and the Quran was also highly challenging, she said. Women in the camp use village terms not found in standard Arabic, and all excerpts from the Quran had to be correct, without a word misspelled or omitted.

To produce the book, Fisher connected with a literary agent and a publisher, Goose Lane Editions in her native Canada. Photographer Alex Lau, who had recently left Bon Appétit magazine, signed on to do the photography pro bono, with his expenses paid by the Canadian and Irish embassies. Lau photographed 90 dishes prepared by the women in their homes and more in the camp bazaar. The embassies also helped pay for ingredients and for the women’s time preparing the food.

To gather recipes, Fisher worked with more than 2,000 people over the course of six years — “old people, women, men, people with disabilities, boys and girls, everyone,” she said. Because the recipes are passed down orally, she worked with cooks to create written instructions. She also included Western alternatives for Syrian ingredients and explained the cultural origins of each dish.

Syrian food is widely considered the best in the Arab world, Fisher said. To really capture its essence, she said, “I had to completely change my writing style. I had to write it so somebody would want to eat the page.”

The women shared lore from Arab medicine, such as what time of year to make a dish and what makes it healthy to eat. Fisher captured how the dishes and ingredients draw upon the Quran and Syrian culture and tradition, in which women engage in social cooking, gathering in groups to prepare food for their typically large families. The work is part of Fisher’s larger goal of preserving the culture of the camp and its residents, most of whom come from the southern part of Syria where the revolution originated as part of the Arab Spring of 2011-12.

To tell the story of Zaatari and its culinary traditions, Fisher needed to organize a large number of contributors with generations-old recipes handed down by word-of-mouth, and she also needed to get photo consent from hundreds of people living across the camp and world. It presented a daunting information challenge.

“It took all of my LIS and iSchool expertise to do this book,” Fisher said. “I couldn’t have done what I’ve done if I wasn’t a professor at the UW iSchool.”

“Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the World’s Largest Refugee Camp” is available from major online retailers, and all its royalties will go to the people of Zaatari. Listen to a recent CBC Radio podcast featuring Fisher or contact her at fisher@uw.edu.

“Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the World’s Largest Refugee Camp” is available from major online retailers, and all its royalties will go to the people of Zaatari. Listen to a recent CBC Radio podcast featuring Fisher or contact her at fisher@uw.edu.

Pictured at top: Kibbeh Mohabala, a steam-fried dish special to the Houran region.