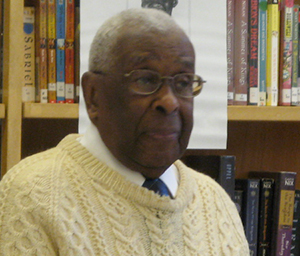

In the Fall 2005 issue of iNews, the iSchool profiled Spencer G. Shaw. This article has been adapted below:

Spencer Shaw picked his profession by the time he reached high school. Books and reading were important parts of his family life, and so was the Northwest Branch of the Hartford, Connecticut, Public Library.

Spencer Shaw picked his profession by the time he reached high school. Books and reading were important parts of his family life, and so was the Northwest Branch of the Hartford, Connecticut, Public Library.

“I was impressed with the work of the librarians and the services they rendered to the public,” he remembers. “Librarian Desier Moulton made it a welcomed place for the whole neighborhood. On Saturday mornings we gathered for the weekly story hours, where we were introduced to rich sources of folk literature from around the world. That’s what I admired.”

Information School Emeritus Professor Shaw carried on that tradition during a nearly seven-decade career as a public librarian, educator and world-renowned expert on storytelling and library service to children. The American Library Association called him an “authentic and forthright spokesperson for children and youth librarians, contributing enormously in motivating and guiding the nation’s youth.”

When Shaw retired in 1986 after 17 years on the UW faculty, the Information School (then the Graduate School of Library and Information Science) established the Spencer G. Shaw Lecture Series. Every November, a leading figure in children's literature comes to the UW campus to speak to students, librarians, teachers and parents. Famed authors and illustrators such as Tom Feelings, Maurice Sendak, Ashley Bryan, Margaret Mahy, Gary Soto, Laurence Yep, Theodore Taylor, Susan Cooper, Katherine Paterson, Milton Meltzer, Jerry Pinkney, Grace Lin, Sharon Draper, and Ryan Reynolds have participated.

Growing up during the Depression in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood in Hartford, Connecticut, Shaw was the only African American student in his grammar and high school classes. His father, who worked in the Hartford National Bank & Trust Company, took an active role in community affairs. In the 1950s, the chief executive officer of Hartford’s G. Fox and Company department store approached Shaw’s mother, a homemaker, to serve as a consultant to the personnel department in training its minority employees for better positions as salespersons, section managers and buyers.

“My parents were not only mentors but role models,” Shaw says. “They encouraged all of us (two brothers and four sisters) to go into whatever field we wanted. They stressed a college education, and that we were to be prepared when the moment came that the doors that were closed to us because of race would be opened. They told us that it was our duty and responsibility to remember that we are members of the Shaw-Taylor families. Our roots were deep. We were to accept challenges and not to compromise our principles.”

As president of the senior class at Hampton University, an HBCU (Historically Black College or University) in Virginia, Shaw was invited to meet with school President Arthur Howe to discuss matters related to commencement. When asked what he wanted to do next, Shaw answered librarianship. Six weeks later, he received a Carnegie Corporation Fellowship specifically earmarked for African-Americans going into that field. Upon the advice of his sponsor, he chose the University of Wisconsin.

During the summer of 1940, Shaw worked at the Keney branch of the Hartford Public Library as a prerequisite for his degree, and after he graduated in 1941, the library director invited him to become manager of that branch. “My appointment earned him an epithet from a colleague of a neighboring city, but he didn’t care,” Shaw recalls. “He wanted to break the color line.”

In his work, Shaw never encountered resistance from colleagues or patrons to his race or his gender. (When he started, he was one of just three male public librarians in Hartford.) “No one cared,” he explains. “I was getting so much done!”

"Anything to get people to read and use the library."

From the outset, Shaw’s goal was to make the library a major part of its neighborhood, a lower-income area. After completing a demographic profile of the community, Shaw served both children and adults through Saturday-morning storytelling, visits to school classes and assemblies, programs at social service agencies and parks, evening programs for adults and young adults, music programs, a radio program called The Library Has an Answer, and outreach service to homebound students and seniors. “Anything to get people to read and use the library,” he says.

But Shaw still had to prove himself to the old guard on the board of trustees who ran the Hartford Public Library. In his annual report, the board president stated, “Spencer Shaw’s work has been convincing proof that men of his race, high character, ability and good judgment have much to offer and are of great good in combined work with our own. There has never been any question of discipline or race disturbance. It is doubtful that any other library in the country has been more successful in this aspect of library service.”

In response to the board president, Shaw hoped that all future applicants would be considered on merit and not on the basis of race or creed. His response was sent to other board members, one of whom referred to Shaw’s concern about being considered “an experiment”: “He was quite right, for I was of the number who thought the set-up experimental--and I am happy to be convinced of its success.”

From his work in the Brooklyn, New York, Public Library (1949-1959) and the Nassau County, New York, Library System (1959-1970), Shaw gained a reputation in library service for children and in storytelling, which led to workshop engagements, lectures and visiting professorships at colleges and universities: Queens College, Syracuse, Drexel, Kent State, Illinois, Wisconsin, Washington, Hawaii, North Carolina-Greensboro, North Texas and Pratt Institute. In addition to administrative and management responsibilities related to children’s services during this period, he also presented book talks and storytelling in schools, conducted in-service courses for educators (with an emphasis on “Enriching the Curriculum with Library Resources”) and parents (“Family Enjoyment with Children’s Literature”). He made guest appearances on radio and television, worked in programs for the immigrants to learn English, visited hospital wards, conducted summer programs in city parks, and organized and directed storytelling institutes. While in the New York Nassau system, for eight years he also hosted a weekly radio program, "Story Hour on the Air — Let’s Go to the Library."

In 1958, Dr. Irving Lieberman, then director of the University of Washington School of Library Science and formerly Shaw’s colleague in the Brooklyn Public Library, invited him to be a keynote speaker at a children’s literature conference in Seattle. He invited Shaw back to teach in the summers of 1961, 1963 and 1966. “He kept urging me to teach full-time at the University of Washington,” Shaw recalls, “but my family and friends were back East.”

"We have to develop cultural understanding and acceptance of others. One channel to use to accomplish this is through storytelling."

By 1970, however, Shaw was ready to move. “I also was invited to teach full-time at the University of Illinois and Syracuse University,” he says, “but I had been to the UW three times and had friends there. In a family conference, my mother asked, ‘Seattle?’ ‘Yes, Mother,’ I replied. ‘But what if you got sick?’ ‘They have hospitals in Seattle, Mother!’” Shaw’s first Seattle apartment overlooked Lake Union, and he immediately fell in love with his view of the city’s skyline and the Aurora Bridge, watching the Husky crew teams practicing and the holiday parade of boats float by.

International commitments in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, Hong Kong, England, the Netherlands, Cyprus, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Brazil strengthened Shaw’s advocacy of multiculturalism in children’s literature. “We are living in a pluralistic society,” he says. “New populations arrive from the Far East and the Caribbean, and Muslims from many parts of the world. None of them has come empty-handed. They all have a heritage, a culture, customs, moral codes of behavior and something to contribute to our cultural tapestry. Diversity should be recognized as a positive thing. We have to develop cultural understanding and acceptance of others. One channel to use to accomplish this is through storytelling.”

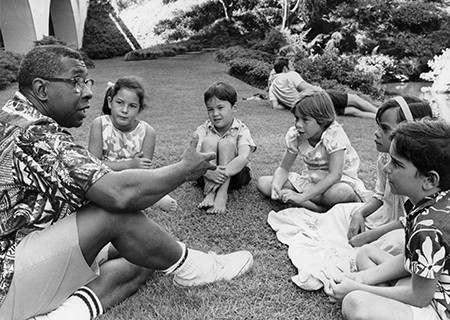

Storytelling perpetuates a folk art tradition that has gone on for ages and ages, Shaw explains. “It presents many genres of literature: myths, fables, epics, sagas, hero tales, legends, folk tales, fiction and poetry,” he says. “It provides entertainment and motivation, builds a bridge to literature, provides a means for personal, social and intellectual growth, and develops a feeling of sensitivity to life and people of the past and present. Without moralizing, it embodies positive ethical, moral and spiritual values.”

Shaw’s skills as a storyteller evolved through many presentations to varied audiences. “The most important thing I learned was to never take the audience for granted,” he says. “Consider not only the ages of the listeners, but many other things--their backgrounds and experience, personality traits, physical and emotional status, language limitations, intellectual and educational levels of the group, general interest and attention span. Facing a school audience, I ask myself, ‘How many have arrived without a proper breakfast or a good night’s sleep? Was the last thing they received at home a yelling in their ears or hug or loving pat on the head? The more you know about your audience, the easier it is to plan your program.”

Still, it’s the story that is most important. “Let the story come through you, and don’t draw attention away from it,” Shaw says. “Thus, inappropriate costumes, props or stage antics should be used in moderation, if at all. Does it fit in with the mood or atmosphere of the story? Does it enhance the telling?

“Through storytelling, one may achieve different ends,” he continues. “A storyteller can kindle emotions or dull the intellect, reveal universal truths or destroy the will to search. A good storyteller can stimulate dormant imaginations and fire the creative spark within all of us.”

UW Libraries Special Collections maintains a collection of Dr. Shaw's storytelling programs, course materials, lecture notes, correspondence, articles, awards, and other materials from the years 1949-2001. You can find a description of the collection here.