What is the Third Estate?, 1789

A meandering pamphlet that suggested 95 percent of the population was doing all the work and getting no representation. Sound familiar?

Transcript

You’ve heard the expression lightning never strikes twice, right? Demonstrably untrue, as anybody who lives in a skyscraper can attest. It’s not metaphorically valid, either—ask those authors whose works line entire shelves, like Stephen King or Sue Grafton or James Patterson.

Sometimes, though, the flash only happens once. While it seems unfair to think of Harper Lee or Margaret Mitchell as “one-hit wonders,” it wouldn’t be all that bad to be known for only one book if that book was sufficiently captivating, powerful, or memorable.

Such was the case for a little-known and less-regarded provincial French priest, the 18th century political equivalent of Dexy’s Midnight Runners, whose ideas had more spark than he did, and whose one well-known work caught lightning in a bottle, captured imaginations and set his tempestuous nation on the path to democratic institutions.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School and given that place and date, you know where we’re headed, right into the teeth of the French Revolution. You might well know the story of the Estates-General and the Tennis Court Oath, though I bet you don’t know what led them there. In the months leading up to early 1789, the temperature was rising, at least politically, and while the writing wasn’t quite yet on the wall, the pens were ready.

The Estates-General were the traditional advisory body to the French king, made of three parts: the clergy of the First Estate, the nobility of the Second Estate, and the Third Estate, everybody else. Things had gotten bad enough that Louis XVI called them into session for the first time in over a century and a half and then started fishing around for ideas of what to do with them. A request to that effect by the king’s minister Necker started those pens churning out pamphlets, generating first a trickle, then a flood, amounting to many thousands by the spring. The “pamphlet” form was of particular moment at the time, since newspapers were uncommon and little attended to. Most of these, though, were densely argued, contradictory, and frankly, confusing. It took a writer of clarity and the gift of a turn of phrase to coalesce those ideas into a simple--one might even say catechistical—refrain. He begins with:

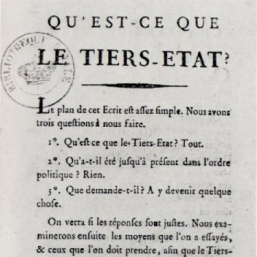

What is the Third Estate? Everything. What has it been until now in the political order? Nothing. What does it ask? To become something.

Catchy, though one must also say, not terribly original. The author in question was Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes, the son of a lesser royal official, who drifted into the church and, after some struggle, found a position as an episcopal assistant, rising through the ranks and eventually moving into the salon culture of the time and the emerging political discussions to be found there.

The pamphlet laid out commonly discussed ideas, though presented in a clear, compelling and understandable way, and importantly in the right place at the right time. His central argument was that sovereignty should come from those who produce, who generate services and goods for the benefit of society. The nobility, on the other hand, were fraudulent, parasitic, and unnecessary. He said the Third Estate can sustain itself and has a right to complain: the nation can’t be free if the Third Estate isn’t. He even undertakes a thorough calculation of what proportion of the population comprises the Third Estate and comes up with 19 out of 20—95%.

The rallying cry of the day was “vote by heads, not by orders.” The traditional structure of the Estates-General called for them to vote as orders, meaning, transparently, that normal people would be continually outvoted 2 to 1. Allow them to vote by person, and make sure their numbers were as large as the others combined, and all sort of interesting things might happen, which wasn’t necessarily what Louis had in mind.

As for the document, “pamphlet” doesn’t really convey the right image; this isn’t the trifold brochure you pick up at an information booth; it came out in three increasingly compendious versions, starting at 86 pages and heading to 180, which apparently Sieyes self-published; the title page and verso of the third edition bear no printer’s name or mark. It was, though, translated quickly into German and English, and had a print run of at least tens of thousands.

His work got Sieyes elected to the last available seat in the Third Estate. However, once his ideas struck fire and galvanized the political mood of the time, he could no longer control them. His positions were shot down numerous times in multiple venues and he left behind a string of defeats and missed opportunities. He was, for example, on the wrong side of the question of confiscation of church lands (which he opposed), and apparently was a poor speaker, so his influence waxes and wanes over the next several decades. He didn’t even prevail during the dramatic Tennis Court episode; it was he who moved that the Third Estate break away and invite the others to join them. That worked, and they swore to stay together until the other two saw the light. Then, though, he suggested they decamp for Paris where they might be safer, but they voted instead to stay put. Awkward.

After the fall of the Bastille, the abbe wafted in and out of a number of positions, including 2 separate constitutional committees, the Convention, the Committee on Public Safety, the Committee of Five Hundred and the Senate, and also participated in an attempt to overthrow the Directory. He wrote quite a bit, though no other of his works had nearly such an effect. In fact, his sputtering career might have saved his life; it’s possible his profile was low enough that he didn’t catch enough attention during the Terror to be bothered with. When asked later what happened during those dark days, he said simply “J’ai veçu.” I survived. Which is more than many could say.

It’s hard, in hearing all of this, not to think of the Occupy movement and their rallying cry of the 99%, almost exactly what Sieyes calculated for the Third Estate. And yet they have lacked what he provided, a central, unifying manifesto and program with goals. So much of the modern movement is driven by social media, which wins easily for speed and reach but maybe falls shorter on depth and texture of ideas. A hashtag, perhaps, can’t do quite the same thing as an extended political argument.

Actually, I’ve struggled to find a recent political manifesto that had substantial impact. The best I can manage is the Republican Party’s Contract With America, which formed the basis of their stunning 1994 Congressional election victory. Right place, right time, right words... a combination that’s hard to come up with, and when the lightning strikes, hard to beat.

References

Scott, S. F., & Rothaus, B. (Eds.). (2004). Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution, 1789-1799. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Sewell Jr, William H. (1994). A Rhetoric of Bourgeois Revolution. Durham: Duke University Press. van Deusen, G. (1932). Sieyes: His Life and Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press.