Voyager 'Golden Records', 1977

Would you want to live forever? Lots of stories warn against the perils of immortality from the Greek myth of Tithonus who was given eternal life but not eternal youth, to innumerable vampire stories and even Doctor Who, and yet the idea still fascinates; what if we could somehow go on? In a sense, we can. In one of the oldest stories known, Gilgamesh tries in vain to become immortal only to discover the only way he can is through his works, and his name lives on thousands of years later. So maybe, just maybe, there’s a chance for us all.

Transcript

Would you want to live forever? Lots of stories warn against the perils of immortality from the Greek myth of Tithonus who was given eternal life but not eternal youth, to innumerable vampire stories and even Doctor Who, and yet the idea still fascinates; what if we could somehow go on? In a sense, we can. In one of the oldest stories known, Gilgamesh tries in vain to become immortal only to discover the only way he can is through his works, and his name lives on thousands of years later. So maybe, just maybe, there’s a chance for us all.

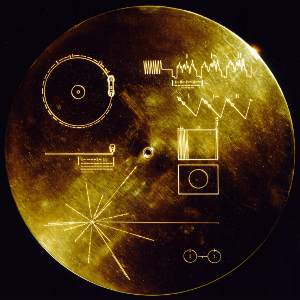

A document that changed the world: Long-playing discs containing recorded sounds and images, attached to the Voyager 1 and 2 Probes and launched into outer space, known as the “Golden Records,” 1977.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. Gary Flandro is a graduate student working part time at the Jet Propulsion Lab in 1965, and runs across a curiosity: for a few months in the late 1970s, the major planets would be aligned in such a way that a spacecraft could use their gravity one after the other to slingshot around the solar system much faster than would otherwise be possible. He plots the course – with paper and pencil – and the Voyager missions are inadvertently born. It takes a bit of subterfuge – JPL initially got Congressional approval for a mission just to Saturn, smiled pleasantly, and then went right on building something more ambitious, certain that nobody in Washington was smart enough to notice. They were right.

The Voyager probes themselves, marvels of technology in their time, are quite modest. Each is the size of a small car, five years and $200 million in the building, boasting onboard computers with an impressive 4K of memory using 8-track tapes. They included instruments to measure mass, gravitation, magnetic fields, radiation and temperature as well as images, and discovered wonders not yet imagined, like volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io and water ice on Europa. They were launched within about 2 weeks of each other in the late summer of 1977, not long after the introduction of the Apple II and TRS-80 microcomputers, the New York City blackout, the first test flight of the space shuttle Enterprise, and mere days after Elvis Presley dies. Or does he…?

They also carry a special cargo. Attached to each probe is a 2-sided long-playing disc of gold-plated copper, 12” in diameter, with a stylus and directions on how to play the record, etched on an aluminum protective cover electroplated with uranium 238 to aid in dating them. These were the brainchild of the extraordinary physicist and public intellectual Carl Sagan, who led the group responsible for the construction and contents of a message from Earth to the universe.

OK great – now – what do you say? And how? It’s hard enough some days to tell your spouse or your kids what’s on your mind, let along beings who might have an entirely different sensorium.

Sagan recalled a childhood visit to the 1939 World’s Fair in New York and the time capsule buried there to be opened in 5,000 years. His group quickly decided the only guaranteed common means of communication with an alien species would be scientific, so the 116 images encoded start with scientific concepts and symbols to establish mathematical and physical bases, then the sun and solar system. Chemistry, biology, human anatomy and, ahem, reproduction (the silhouette of a man and pregnant woman showing the fetus inside is just weird), pictures of Earth, nature, animals and plants. Then, us: culture, dance, sport, school, farming and fishing, eating (including one poor guy munching on what appears to be a grilled cheese sandwich for all eternity), houses, transportation, ending with a sunset and a violin. The first image, meant to help in the decoding process, is a circle, which I don’t think the designers ever fully appreciated for its beauty, simplicity, and unity. Predictably, there was criticism, of the whole thing, of the fact that no negative images were included, even of the idea that we might give away our position completely missing the point that the most important, if not the only, audience is we ourselves.

Many people know the discs contain music – but which music to include? Whole pieces? Snippets? Of what? How do you pick, to represent an entire species and its entire musical history? (Hint: You can’t.) They chose very fine grooves and a playing speed of 16 2/3 rpm rather than 33 1/3 to double the time available, none of which will make any sense to you if you’re under 40, sorry, so there’s about 90 minutes available for everything. We start with a Bach Brandenberg concerto, then gamelan music, Senegalese percussion, a Pygmy girl’s initiation song, Australian Aboriginal songs, and so on. Much attention was paid to the inclusion of “Johnny B. Goode” including a Saturday Night Live sketch predicting the answer we might someday get back would be “Send more Chuck Berry.” The Beatles agreed to include “Here Comes the Sun” but their record company didn’t. Anybody could quibble with their choices; I concede the appropriateness of the “Queen of the Night” aria from The Magic Flute, but seriously, why nothing from The Planets? Too on the nose?

The spoken greetings are less discussed. An initial notion to record each head of delegation to the UN saying howdy failed for a variety of reasons, not least a desire to represent both male and female voices equally; instead people from the foreign language departments at Cornell recorded in 55 languages, allowed to say whatever they liked. In Cantonese: “How’s everyone?”, in Arabic, “Greetings to our friends in the stars”, in Latin, “Salvete quicumque estis = Greetings to you, whoever you are”. We also have “Dear Turkish-speaking friends, may the honors of the morning be on your heads”, and in the Amoy dialect, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” The UN attempt, however, triggered the political necessity to include a message from the Secretary-General, then Kurt Waldheim, who only a few years later was discovered to have had a Nazi past, which is not at all embarrassing in front of the entire cosmos. That in turn meant that President Carter had to have his say, which along with the song of the humpback whale might make up for Waldheim. They also squeezed in a few sounds, of weather, of footsteps, heartbeats and what one journalist believes is Sagan laughing. An hour of his future wife Ann Druyan’s brainwaves. And a kiss.

Naturally, Congress had to horn in with 2 very poor quality images of typewritten lists of space and science committee members, including Barry Goldwater and a bright 29-year-old Al Gore, and out of dozens of names precisely 2 women.

This all illustrates the unavoidably political, fraught, incomplete choices that were made, by a relatively small group largely composed of well-intentioned, Western, Caucasian men, impatient with bureaucratic cupidity and small-mindedness, with limited time and resources, a grandiose vision and their own sets of preferences, lenses and blinders, which could be said of us all. Were this project to be replicated today, no doubt the process and choices would be far different, though you have to give them credit for a sincere and earnest attempt to do the best they could.

So, you might be asking, what kind of “document” is this? Manifestly and literally, it’s a “record,” in both senses of the word. Sagan was originally inspired by a time capsule, that’s another possibility, it’s also been referred to as a mixtape or a love letter, though to my mind it shares characteristics with lots of other documentary forms too: it’s a letter of introduction, it’s a scrapbook or family album, an invitation, a map, an instruction manual, a primer, a work of art, an intelligence test, both for “them” and for us I think. It may also be the last surviving human artifact and thus perhaps an ark. It’s all these things and more, though for me the best metaphor is a message in a bottle, likely the ultimate message in the ultimate bottle.

The Voyagers still go on, still sending back data that takes nearly 20 hours to reach Earth. Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause, the outermost fringes of the solar system, in 2012, and is over 20 billion km from Earth, the furthest object of human construction, traveling nearly 40,000 miles per hour. The first exoplanet wasn’t discovered until a decade later, so it’s not aimed in any particular direction, and in around 100 million years (assuming the first Star Trek movie is wrong), it will have traveled 5,000 light years, about 1/6 the distance to the center of the galaxy.

One day, by about 2025, the power sources will give out, the signals will stop, and the probes will go silent, likely without the chance for a final farewell or bon voyage. However - barring an unlikely collision or even less likely interception, the discs will go on, more or less forever, bearing our messages, our songs, ourselves. I can’t imagine Sagan and his colleagues truly believed either of these would ever be found, let alone decoded and if so, we’ll never know it. But - bound up in the attempt is one of the most basic of human desires, to be remembered and understood. We were here, we mattered, and we have stories to tell.

A message in a bottle is typically an act of desperation, the only way you can conceive of to get a message out. Here, however, it’s an act of hope – and as we learned from another Greek myth, of Pandora, when all else is gone, hope remains.

Sources:

“Contents of the Voyager Golden Record - Wikipedia.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contents_of_the_Voyager_Golden_Record.

Sagan, Carl. Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium. New York: Random House, 1998.

———. Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record. New York: Ballantine Books, 1979.

“The Loyal Engineers Steering NASA’s Voyager Probes Across the Universe - The New York Times.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/03/magazine/the-loyal-engineers-steering-nasas-voyager-probes-across-the-universe.html?_r=0.

“The Mix Tape of the Gods - The New York Times.” Accessed August 20, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/05/opinion/05ferris.html.

“Voyager - Making of the Golden Record.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/voyager/golden-record/making-of-the-golden-record/.

“Voyager - The Golden Record.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/voyager/golden-record/.

“Voyager - The Interstellar Mission.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/voyager/.

“Voyager Golden Record - Wikipedia.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_Golden_Record.

“Voyager Golden Record: 40th Anniversary Edition by Ozma Records — Kickstarter.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/ozmarecords/voyager-golden-record-40th-anniversary-edition.

“Who Is Laughing on the Golden Record? - The Atlantic.” Accessed August 20, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/06/solving-the-mystery-of-whose-laughter-is-on-the-golden-record/532197/.

“Why NASA’s Interstellar Mission Almost Didn’t Happen.” Accessed August 20, 2017. http://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/08/explore-space-voyager-spacecraft-turns-40/.