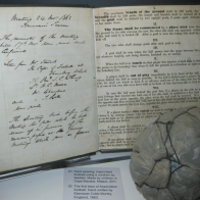

Rules of Association Football (Soccer), 1863

Joe Janes looks into the game’s history and rules and finds nothing simple about them, thanks in part to the English.

Transcript

Doesn’t this just bug you? The game is starting to get exciting. Your team is driving, picking up yards in chunks, and a nice little run ends right about at the down market. Maybe it’s a first down, but it’s close. So close in fact that they have to measure, and in come the chains and the game comes to a screeching halt. OK, I totally get that there has to be a point at which it’s a first down, and short of that point, it’s not. But a system where one guy plops the ball down where he thinks it was when the running back’s knee was down, and then another few guys come in to measure with chains based on where they thought it was before, to see if any tiny little part of the ball extends beyond the stick? Downright medieval. And people who have no idea how, say, the electoral college works on how a bill becomes law, can spout chapter and verse about what constitutes a touchdown or a legal reception. Remember: one knee equals two feet, and part of the ball that breaks the imaginary plane counts, and the goal line goes around the world. Sheesh.

Rules are rules, though, and nobody knew that as well as the people who tried to bring some order and coherence to an ancient and sometimes dangerous game, now generally regarded as the most popular sport in the world, and in the process tells us something about what makes creativity possible.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. People have been kicking and throwing balls since there have been people and balls, or even things that act like balls. The Chinese game of cuju arose in the second century BCE and lasted until the Ming Dynasty; the 12th century Japanese game of kemari involved kicking a ball to keep it in the air as long as possible, and look good doing it; the most desirable end was to catch it in the folds of one’s kimono. The indigenous peoples of Australia and North America had games not unlike soccer, but it’s in Mesoamerica where sports history is the strongest; at least 3000 years ago there was a ball game, so deeply ingrained in the culture that it’s described in the Popul Vuh and its rituals bound up in their creation story and belief structure. These people also had the advantage of plants that could produce a form of rubber, so their balls could bounce, a source of amazement and even concern to the Europeans who, shall we say, largely put an end to the fun.

It falls, of course, to 19th century England to codify and regulate all this, as they did with other sports such as boxing as early as 1743, rowing, horse racing, and cricket. A game called “football” is the subject of a proclamation by Edward II in 1314 forbidding its play as a breach of the peace; it must have been a rough game without rules, causing property damage, riots and even death at times, with an unlimited number of players, in the streets, using bushes and houses as goals. Shakespeare refers to “football players” as an insult in King Lear, but slowly over the decades and centuries standards started to form.

It was the English public schools that serves as the incubators and crucible for football, each developing their own slightly different in-house version of the game, leading to the inevitable confusion when they wanted to play each other. Compromise rules were compiled in Cambridge in 1846, though they didn’t get wide acceptance. A collected set was published in 1861, revealing the depth of the differences, and this led to a series of meetings in 1863 to sort this out once and for all.

These meetings were held in November in taverns across London, with people from a number of the important clubs in the area, to try to craft a set of rules that everybody could agree on. Not an easy task; they got stuck on whether the game should involve catching or not, and whether “hacking”—which we would call “kicking in the shins”—should be allowed. The gentleman from the Blackheath Club opined that eliminating hacking would “do away with the courage and pluck of the game, and I will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you with a week’s practice.” His intellectual inheritors can be heard today in rueful debates about outlawing helmet-to-helmet tackling in the NFL and fighting in the NHL.

That is also, though, an acknowledgement of the importance and centrality of rules to soccer and indeed to any sport. A sport, or a game, or a society for that matter, without rules, isn’t worthy of the name. The rules are the game, and the game is the rules, no matter how ludicrous or overspecified they might be. All baseball fans, not to mention pitchers and batters, know that the strike zone is different, umpire by umpire, even pitch by pitch, but there has to be a strike zone. The debate over the charge vs. block in basketball will never end, nor over judging in sports like gymnastics or figure skating.

Increasingly, these rules extend beyond the field of play; consider the torturous NCAA compliance guidelines which require entire staffs to understand and work with, salary caps and more recently doping rules; internationally there is now even a parallel legal structure in the form of the Court of Arbitration for Sport to sort out disputes.

All of which is part of a desire to get it right. That’s why fencing uses automated systems to detect touches, and why tennis adopted the challenge system which (in theory) can see where a ball strikes the court within a 1mm margin of error. It’s also why instant replay is so seductive no matter how long it takes or how counterintuitive the results are. And yet judgment, and necessarily error or least subjectivity, is part of the quintessentially human nature of sport.

Sports rules, like any rules, provide structure. As one author has said, a sport without rules is just play. They create standards, limitations, boundaries, which is why most sports have lines of some sort. Mainly they provide constraints, and constraints promote creativity. Without those kind of constraints would we have the desperate Hail Mary pass, the stunning alley oop, the gracefully placed drop shot or the beautiful bending shot of David Beckham? Unlikely, which is why they play, and why we watch.

References:

Football. History. (1899) (New ed.). London [etc.]: Longmans, Green and co.

Football’s Historic first Rule Book arrives in Manchester :: Latest news :: About us :: National Football Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved February 5, 2013, from http://www.nationalfootballmuseum.com/about- us/latest-news/2012/05/soccers-historic-first-rule-book-arrives-in-manchester/

Goldblatt, D. (2008). The ball is round: a global history of soccer (1st Riverhead trade pbk. ed.). New York: Riverhead Books.

Laws of the Game - FIFA.com. (n.d.). FIFA.com. Retrieved February 5, 2013, from http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/footballdevelopment/technicalsupport/refereeing/laws-of-the- game/index.html