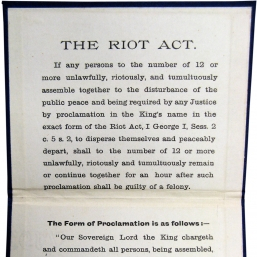

Riot Act, 1714

When does a gathering of people become a riot? Literally, when someone reads The Riot Act and closes with “God Save the King!”

Transcript

You know the expression “just say the word,” right? It’s a common phrase used to indicate you’re waiting for or expecting an instruction or permission—just say the word and I’ll help out, or pick up dinner, or hire that hit man for you. Those instructions can be trivial or profound, depending on the circumstances, and even when there’s more than just one word involved, the meaning remains clear—merely speaking, and hearing, the words is all that’s needed to carry out somebody’s wishes.

About three centuries ago, in a time and place of turmoil and upheaval, a law was passed, now largely forgotten except in the common expression it gave rise to, where saying the right words at the right time were meant to bring order, on pain of death for those who chose to ignore them.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. The early 18th century was not an easy time in a Britain newly united. By the time the Hanoverian George I ascended to the joint throne of England and Scotland in 1714 after the death of the childless Queen Anne, there had been over a century and half of squabbling over succession all the way back to Mary and Elizabeth, a Civil War, a republic, the restoration of the monarchy, and the seemingly never-ending struggle for supremacy between Catholicism and Anglicanism. The Glorious Revolution in 1688 firmed up the Protestant character of the throne, and then the supporters of Catholic claimant James II rose up in what is now called the Jacobite Rebellion.

A series of riots starting in 1710 between competing groups of Tories and Whigs were the last straw, and in 1714, the same year Parliament created a prize for the first person to figure out longitude and thus make ship navigation safer, they passed an act to put a stop the disorder in the country once and for all, to take effect the following year: the Riot Act. The act itself allowed local officials, including sheriffs, mayors, and justices of the peace, to decide that any gathering of more than 12 people was “unlawfully, riotously, and tumultuously assembled together,” and thus to proclaim them as a “riot.” This distinguishes them from a “rout” which is an attempt to commit a riot, or “unlawful assembly,” which common law helpfully defined as...an assembly of people to do something unlawful.

In any event, once that decision and declaration is made, the rioters would have an hour to disperse or face being charged with a felony, punishable by death. A tool as powerful as that is oh so tempting, so its eventual use for political purposes comes as no surprise. In addition, the Act allowed authorities to use force in dispersing a riotous crowd, and for good measure bystanders who helped out in the process and maybe, um, hurt or killed anybody would face no charges of their own.

Here’s the thing, though. The sheriff or mayor can’t just make this decision and rely on people knowing about the law, or wave a copy of it at them. He has to say it. Out loud. “[A]mong the said rioters, or as near to them as he can safely come, with a loud voice.” There’s an obvious hitch here; your average rioter, even in genteel, pinky-raising Britain, is not exactly amenable to being stopped mid-rumpus to be told to knock it off. And, as later court decisions would declare, the entire operative paragraph in the Act, consisting of all of some 53 words, had to be read, and heard, including the closing “God Save the King!,” for it be valid.

By 1837, the penalty was reduced to transportation for life (to Australia, mostly); the last time it was used was apparently in Glasgow in 1919, before being repealed in 1973. Versions continue to be active in other places, including several Australian states, Canada (where it was read out following the Vancouver Stanley Cup riots in 2011) and the US, starting in 1792 and persisting to this day. We, though, only require 3 people to make up a riot. I guess cause we’re just better at it.

It’s tempting to think of this as an oral document—but it’s not; it’s written down and everything. It’s more correct to say that this is a document that has to be oral to work. It share more in common with things like oaths, which we still make people recite and swear out loud. For that matter, it feels as though it most closely resembles an incantation or magic spell, whose mere presence doesn’t work until read out loud, or a religious service such as the Mass. All of those have a ceremonial or ritual aspect, a time, place, circumstance; without the ceremony, without the spoken words, it’s an unleavened wafer—with it, it’s the literal and physical body of Christ. These are all examples of what linguists call “speech acts”, things we say that cause something to happen, or to change, or to be. Think of a promise, an excuse, an invitation, thanks, apologies, congratulations. Several categories of these have been identified; the Riot Act seems to be an example of both a “directive” act like “Come here” which cause the hearer to do—or stop doing— something, and a “declaration” which changes the state of the world. As when a judge “pronounces” sentence or a that a couple is married. A group isn’t a “riot” until the sheriff says so, and they hear him—this had to be heard to take effect as well—and then they are. Because...he said so, and the law says he can. If anybody else did, it wouldn’t work.

Times and circumstances now are different, as are tactics for quelling riots—water cannons and pepper spray seem to be more in vogue than a good stern talking to. “Reading the riot act” persists now almost entirely rhetorically, meaning a scolding. But of course, rhetoric is all it ever was— words written to be spoken and heard, taking on the power they were given until no longer needed, and then eventually taking on a new meaning of their own.

References

10 USC Chapter 15 - INSURRECTION | Title 10 - Armed Forces | U.S. Code | LII / Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Retrieved June 10, 2013, from http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/subtitle-A/part-I/chapter-15

Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. (2006) (2nd ed.). Amsterdam ; London: Elsevier. Full text of the Riot Act (c. 1714 - 1715). (n.d.). Retrieved June 10, 2013, from

http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext05/rtact10h.htm International encyclopedia of the social sciences. (2008) (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference

USA/Thomson Gale. Riot Act - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. (n.d.). Retrieved June 10, 2013, from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riot_Act Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: an essay in the philosophy of language. London: Cambridge U.P. Searle, J. R. (1979). Expression and meaning: studies in the theory of speech acts. Cambridge, Eng. ;

New York: Cambridge University Press. The last reading of the Riot Act. (2009, January 30). BBC. Retrieved from

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/scotland/glasgow_and_west/7859192.stm