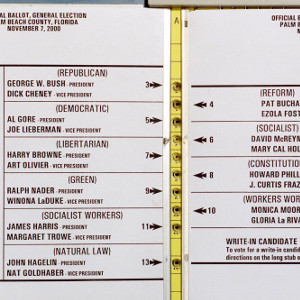

Palm Beach County 'Butterfly' Ballot, 2000

Electorally, the only poll that matters is the last one – actually casting a vote, which seems comparatively straightforward. You vote for the person you want, somebody in charge counts ‘em up and then we find out the winner. As if.

Transcript

What did you mean by that? For years, I’ve taught courses in quantitative research methods, which includes how to construct and administer surveys. You hear these all the time, including the ubiquitous polls that build to a fever pitch with the approach of any election, and the techniques involved have become increasingly complicated and sophisticated over the last several decades.

However, as I always tell my students, when you’re doing this sort of work, people are a problem. It’s very easy for somebody to answer a telephone poll or check a box on a survey form that says they’re going to vote for X or believe Y or think we ought to do Z, but it’s quite another to know, really know, really really know, what’s going on in somebody’s head. It takes hard work to put together instruments and instructions to do the best possible job of discerning just that.

Electorally, the only poll that matters is the last one – actually casting a vote, which seems comparatively straightforward. You vote for the person you want, somebody in charge counts ‘em up and then we find out the winner. As if. This is a story we all know the end of, and kinda know how we got to the end of, like it or not, but here we’ll focus on how we got to having to get to that end, an end that reverberates several elections on.

A document that changed the world: a ballot, used in the presidential election in Palm Beach County, Florida, now known as the “Butterfly Ballot,” 2000.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. There are lots of stories to be told about the 2000 election, legal, constitutional, moral, judicial, social, political, probably a marine biology or art history angle I haven’t run across – but I’ll let other people tell those. Here we are concerned with a document, actually two working together, which had intent and purpose and function and how that worked, or didn’t. A “ballot,” which we borrowed from the Italian for the “little balls” used in elections in the Venetian Republic, is intended to allow someone to cast a vote, so that those votes can be counted and a democratic decision made. So like any document, it must be designed to appropriately fulfill those functions.

This brings us to Theresa LaPore, who began as a file clerk in the Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections office in 1971, age 16. By 2000 she had been elected Supervisor and thus it fell to her, as it did in every other county in Florida, to decide on the design for the ballot for the upcoming election. About a quarter of Palm Beach County residents then were over 65, and she had been involved with a federal task force on voters with visual impairments and disabilities, so she felt it was important to be sure candidates’ names would be clearly visible. Since there were so many (10) candidates for president and vice-president, listing them on only one side of their Votomatic punch-card ballot instructions would make the print really small. (Imagine these instructions like the pages of an open book.) So she decides to use larger print and both pages astride the narrow exposed column of the actual voting card, with numbered arrows pointing from candidates names to the appropriate holes to punch to vote for them. To be clear, the punch card was the actual ballot; she designed the instructions, and the combination had to work together to work.

In a 2001 interview, she describes her hazy memories of that election day, arriving at the office at 4 a.m. to deal with the usual hectic pace. A couple of elderly gentlemen come by the elections office mid-morning to complain that they had been confused, but it’s only as the day progresses and more calls come in, followed by agitated visits from elected officials, particularly Democratic ones, that she starts to realize there’s a substantial problem. In her desire for readability, she sacrificed – almost everybody believes inadvertently – another key design principle: usability. It’s not hard to see the word “Democratic,” listed second on the left (because the Democratic candidate had placed second in the most recent gubernatorial election, to Jeb Bush) and then follow along to punch the hole immediately to the right, the second in the column, which is really for Pat Buchanan, listed and with an arrow on the other side, who ran on the Reform Party line. Whoops.

Later analysis would suggest that between 2,000 and 3,000 people in Palm Beach County voted for Buchanan by making that mistake, along with uncommonly large numbers, thousands, of other problems: overvotes (people voting for more than one candidate for the same office, such as both Buchanan and Gore), undervotes (people who voted for other offices but not for president) or what we all later learned way too much about, problems with chads.

Remember chads? The word itself, of uncertain origin, traces back to the late 1950s and refers to the little bits that get punched out of early computer storage technologies like cards and paper tape. Basically confetti. A good solid punch hole is made, chad falls away, everybody’s happy. But a half-hearted, uncertain, hurried, indifferent punch, and you can get one of (not kidding here) 6 different kinds of problematic chad: dangling, dimpled, hanging, pierced, pregnant and swinging. If this weren’t so serious, those would sound like outcomes of some late-1960s suburban pool party.

People make mistakes when they vote all the time, and not just of the buyers’ remorse variety. With any system, whether you touch a screen, pull a lever, fill in a bubble, whatever, you can get it wrong. But here’s the thing – how would anybody else know? Buchanan got way more votes than anybody would have expected. Let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that a confusing ballot caused that. How many? Which ones? How do you really know what’s in somebody’s mind at the fateful moment? The endless discussion in the weeks of haggling over all this afterwards focused in no small part on “voter intent,” which is next to impossible to discern, even when trying to examine hanging chads, by hand, one by one, using magnifying glasses, one of which is now in the Smithsonian, as eventually happened..

The chad deal is largely separate, an artifact of using a punch card system. It underscores, though, the difficulties inherent in the simple counting of large numbers of things. Ask 10 people each to count a stack of a few dozen pieces of paper, and they’ll likely all come up with the same number, maybe a stray one or two here or there. Make it a few million, and watch the fun. Machines are better, though issues of maintenance, manufacture, programming, improper feeding or training can intrude here as well. As a county judge on the canvassing board said, when tested seven times on pre-programmed ballots, the machines had 100 percent accuracy every time; in a manual recount “no two people get the same results.” For that matter, it appears that most of the increase Gore saw in a machine recount was because some chads were knocked loose by being fed through a second time.

In a not-close election, these kinds of issues about design, error, inattention and lots of others have marginal impacts. Decidedly not the case in 2000, hence all the legal and political wrangling that went on all the way to the doors of the U.S. Supreme Court weeks later as the world waited. In the larger context, this is all complicated by the highly decentralized patchwork American electoral system, where critical decisions are made at the state and county level, to which almost nobody pays any attention unless something goes terrifyingly astray and then people freak out until they forget all about it again. At least we can rest easy knowing that nobody is actively trying to distort the electoral system for their own purposes. Imagine how much worse that would make things.

The butterfly ballot has taken its place in the Awful Design Hall of Fame, along with the Three Mile Island control system and the O-rings on the Challenger space shuttle. The National Institute of Standards strongly recommended the elimination of Votomatic systems as far back as 1988. “Design” is something lots of people do, and digital tools have made it more commonplace, think of all the miserable PowerPoint slides and resumes and invitations you’ve ever seen. It’s a common activity, and like many common activities, to do it well takes time, experience, training, talent – and, critical testing and iteration to make sure the end product does what you want it to do and not something else. The sample ballot had been sent to the candidates, party chairs and all 655,000 registered voters and no complaints were raised. It wasn’t until people tried to actually vote, to actually punch holes, that it all started to go wrong.

It seems only fair to give the last word to Theresa LaPore, who left the elections office in 2005, followed by many years of service to a number of volunteer and community organizations. When asked in 2001, “Who do you believe won Florida?” she said, “I don’t know. Too many variables. Too many factors.” Couldn’t have said it any better myself.