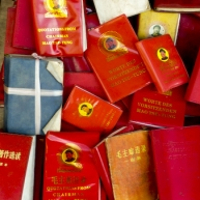

Mao’s Little Red Book, 1964

Mandatory reading for 99% of the population of China and a lesson on how controlling the information can control a whole culture.

Transcript

Who said “there’s nothing certain in life but death and taxes”? You can find that sardonic quote easily, in lots of writings and speeches; there’s also a movie with that title, an LA rock band, even a brand of black beer. Chief Justice Roberts used it in his noteworthy majority decision upholding the health care reform act, citing, as most people do, Benjamin Franklin as the author, in a 1789 letter to Jean-Baptiste Leroy. Dig a little deeper, though, you find that the first known use of that aphorism is in a play by Christopher Bullock called Cobler of Preston from 1716, almost 75 years before Franklin. This sort of thing happens all the time—if you’re stuck, cite Mark Twain, Shakespeare, the Bible, Oscar Wilde, or Casablanca; they’re always likely contenders.

Quotations are often used in wedding toasts, graduation speeches, epigraphs; they seem to be designed to add a bit of panache, or oomph—if Dorothy Parker said this, it must be right, so there. And there are lots of sources, good, bad, and indifferent, that are designed to help find just the right one for just the right occasion. For about a generation, though, in the most populous nation on Earth, there was only one source of quotations that mattered, because the words of only one person mattered—until they didn’t.

It is indeed a little red book, an unimposing little thing, barely 5” high, bound in red vinyl; it sits very comfortably in your hand. What it lacks in size it more than made up for in sheer numbers. There’s no way to know how many copies were printed, since the work was done in multiple places; a more or less official count puts the total number at just over a billion, including multiple editions in Chinese, in dozens of other languages, in recordings, even in Braille. It is undoubtedly one of the most printed and widely distributed books of all time. It contains 427 quotations in 33 chapters, covering such broad topics such as “War and Peace,” “Unity,” “Discipline,” “Criticism and Self-Criticism,” along with old favorites like “Imperialism and All Reactionaries are Paper Tigers,” and “Correcting Mistaken Ideas.”

Mao didn’t write this book; it’s a compilation of quotations drawn from his writings and speeches over almost 40 years, reaching back to 1926, conceived by Defense Minister General Lin Biao and emerging from a daily feature in the People’s Liberation Army newspaper.

Lin Biao wrote an endorsement, in calligraphy, exhorting the people to “study Chairman Mao’s writings, follow his teachings and act according to his instructions.” Promoting the Little Red Book added to his luster and prestige, and by 1969 he was named Mao’s successor. Then the rumors and character assassination started, and by 1971 he was dead in a mysterious plane crash, disgraced, and the people were instructed to tear out his endorsement page from all copies. Today, in an odd twist of fate, intact and undefaced copies can fetch many thousands of dollars on the collectibles market.

The goal was for 99% of the population of China to read it; it was an unofficial requirement to own, read, and carry it at all times during the Cultural Revolution. It was often given as gift on auspicious occasions. Studying the Quotations was required in schools and workplaces; it was also used as reading tool in the army, and a simpler, primer form was also printed.

The production of this work on such a massive scale was an enormous undertaking; hundreds of new printing houses had to be built specifically for this purpose and sufficient resources and printing presses had to be procured. This pushed the limits of the Chinese printing industry, disrupting plans for other ideological works. By one estimate, over 650,000 tons of paper was used to print this one work over a 5-year period.

The quotation that’s likely the most widely known and cited, “let a hundred flowers bloom” is, as is so often the case with quotations, incorrect. In a 1957 speech, Mao said “Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting progress in the arts and the sciences and a flourishing socialist culture in our land.” Whether or not that was intended to encourage dissenting heads to pop up, so they could be more easily lopped off, isn’t clear, but the strategy did work.

Mao dies in September of 1976, and by the late ‘70s the Cultural Revolution is ending. The Little Red Book falls out of favor; the government discourages it, ceasing printing in 1979, and millions are later destroyed, though printing does resume in 1993 for the centennial of Mao’s birth. Today, it’s more of an object of nostalgia and mild curiosity, certainly no longer the force it once was.

The point of all of this, it seems obvious, was indoctrination and control. If everybody in your country is, literally, reading from the same page, then managing what and how they think is made considerably easier, and for about a decade or so, that worked. Although this is one of the clearest examples of the use of a text to reinforce an authoritarian regime, it’s by no means the only one; Mein Kampf was distributed free to all newlywed couples and soldiers on the front during the Nazi government years.

Now, of course, things are more complicated. What’s a tyrannical government to do if they want to control what their people read and think? Would Mao have a Twitter feed? There are parts of the Quotations that read that way, though many go on at considerably greater length, and hashtags like #dowhatisay would quickly grow tiresome, I’d imagine. The one- way world of publication and distribution has yielded to a more complicated, two-way world of social networking, which fosters and prizes participation, discussion, engagement, and sharing rather than consistency, enforcement, and control.

Unless, that is, you control the pipelines. Social networking only works if you’ve got access to a network to be social on, and are free to use it as you want. A number of governments have decided their best option is to keep a firm hand on the tap, and restrict what the Internet is within their borders. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Cuba, Belarus, and Burma are among the countries with such policies, along with, of course, China. While it’s understandably difficult to know the exact extent of their grip on Internet use, it’s likely there are many thousands of people employing techniques such as blocking specific Internet addresses or web pages, scanning discussion groups, blogs, email and Twitter feeds for forbidden topics, and filtering results on search engines in response to certain query words. A robust and innovative set of tactics to circumvent these measures goes on, leading to a cat-and-mouse game of intellectual freedom and repression.

Compared to this Great Firewall of China, as it’s popularly known, the Little Red Book seems somehow quaint and toothless. The resolute and forthright people clutching and brandishing them proudly in propaganda posters of the time would have had no idea that within 50 years their revolutionary handiwork would evolve from turning the pages of a book to tapping on a computer mouse, clicking away freedom of expression for over a billion people.

References:

Oliver Lei Han. Sources and Early Printing History of Chairman Mao’s “Quotations.” (2004). www.bibsocamer.org/bibsite/han/index.html Quotations from Chairman Mao - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quotations_from_Chairman_Mao

“Quotations from Chairman Mao” has become a hot collectibles. (July 13, 2004). news.xinhuanet.com/collection/2004-07/13/content_1595108.htm

Quote...Misquote—A Commentary by Fred R. Shapiro | Yale Law School. (July 21, 2008). www.law.yale.edu/news/7399.htm