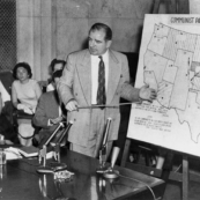

Joseph McCarthy’s List, 1950

Sometimes a document can be devastating — can ruin lives and change history — even if it doesn’t really exist.

Transcript

Has anybody seen my list? Just like my mom, I’m a list maker, things to do, errands to run, groceries to buy, people to invite to a party. None of which guarantees that any of it will get done, mind you, but there’s comfort in the making and even more satisfaction in eventually crossing something off. I know I had it here a minute ago.

Lists are a tool for reminding, and for memorializing, ranking, or enumerating. It’s also a way to categorize or group things or people; you’re either on the list, or you’re not.

Naturally, a list helps mostly if you can lay your hands on it. Although perhaps...not always. Maybe the idea of a list, the paper, it’s supposed to be written on, and how widely you wave it and how loud and often you yell about it is all that really matters. Sometimes, when the circumstances are right, what isn’t there can be more formidable, and more believed, than what is.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. No recording was made of McCarthy’s speech to about 275 people on the night of February 9 for Lincoln Day at the Ohio County Republican Women’s Club in the Colonnade Room of the McClure Hotel, so reports differ on exactly what he said.

There was a prepared text, though at least some people said he spoke largely extemporaneously. Though news reports and personal accounts varied, the version he later entered into the Congressional Record contained lines that have rung down the years: “In my opinion the State Department, which is one of the most important government departments, is thoroughly infested with Communists. I have in my hand fifty-seven cases of individuals who would appear to be either card carrying members or certainly loyal to the Communist Party, but who nevertheless are still helping to shape our foreign policy.”

Well. First of all, that number. This version of the speech says 57, which he repeated in later interviews. It appears to have come from a report by staff of a Congressional subcommittee, who found 108 “incidents of inefficiencies”—but no Communists—in State Department loyalty files. Only 57 were still employed, of whom more than half had already been cleared by the FBI. Multiple reports from the speech, however, reported he actually said he had 205 names, which he continually later denied. That number sprouted from a 1946 letter from then Secretary of State Byrnes, replying to an inquiry about 4000 or so employees who had been transferred to State from other agencies. 285 of them had negative recommendations, 79 of whom had been “separated from the service” leaving 206, which mistakenly became 205. In later rants, the number bounced around between those, sometimes 81 for variety, and eventually 10 or maybe only 9 investigated by McCarthy’s Senate committee.

None of which mattered, since the seeds were sown, in ground that was made fertile by serious and possibly justified concerns about the growing influence and power of Communism on the world stage and perhaps at home as well. In early 1950, the Cold War was in full flower; the previous year saw the blockade of Berlin, the first Soviet atomic test, and the formation of East Germany, the People’s Republic of China, and NATO; North Korean forces would invade the south later that June.

McCarthy’s activities were embraced by the far right, as well as what’s been called a broader “coalition of the aggrieved” of people who were just unhappy about the changing post- war world, about the UN, the ongoing programs from the New Deal, and for that matter water fluoridation, mental health programs and even polio vaccinations, all of which could be, after all, Communist brainwashing or poisoning plots.

And for a while, this all worked. Blacklists. Most infamously perhaps in the entertainment industry in the guise of Red Channels, published later in 1950 by a magazine called Counterattack and listing dozens of names of people with alleged, if in many cases very tenuous, Communist ties. Apparently, Gypsy Rose Lee spoke at a meeting of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League and “entertained” at a dance of the NY Council of the Arts, Sciences and Professions. Being a stripper was OK, but these were beyond the pale, so off of TV and radio she went. It was much more serious for many; one researcher has estimated several hundred people were imprisoned and perhaps 10,000 or more lost jobs, in some cases just for being subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee or pleading the Fifth.

This leads us to the $64,000 question. (Which, by the way, wouldn’t premiere on TV for 5 years). How did this happen? How could a little-known and less-regarded senator whip up all the frenzy he did with a list that likely didn’t even exist? Let’s start with Senator McCarthy’s, shall we say, complicated relationship with the truth. A letter of commendation on his war record as a Marine corps tail gunner, purportedly signed by his commanding officer and Admiral Nimitz, turned out to have been written by McCarthy himself, his “war wound” came from a ceremony for sailors making their first crossing of the Equator, and in his Senate campaign, he went after the legendary sitting Progressive senator Robert LaFollette, Jr. for not enlisting and for war profiteering. The facts, that LaFollette was 46 on Pearl Harbor Day and that McCarthy himself made about as much in wartime investments, needn’t have bothered anybody, right?

But again...why, and how? Why was he believed? Yes, there was a ready audience, and yes, an undercurrent of suspicion and fear of Communism was already at large; the House Un- American Activities Committee had been hard at work since 1938 with earlier investigations as far back as 1918. But still, and I can’t emphasize this enough—there was no list. Or at least no actual list at the time of the speech or, in reality, in any meaningful way going forward.

This story, then, is of a document that never really was, which tells us that documents can have influence, even when there isn’t one. People invest “documents”, or in this case pieces of paper, if there even was a piece of paper, which somebody says is a “document”, with a number of properties. And if that somebody is a Senator, and if those people are ready to hear and to believe because they’re more than a little scared already and looking for somebody to tell them what to do, all the better. “I have in my hand, a list...” is potent stuff.

Documents, imaginary and real, get authority from circumstance and perception, as well as what they really say and are; their meaning and effect is grounded in part in their actual function, form, and content, and in part in their social context. We, and our actions and reactions, do much of a document’s work. And—if McCarthy’s list was real, if that piece of paper had names on it and survived and was preserved, it would have become an even more important document today—less now about potential Communist sympathizers in the State Department, than of the event, of the time, an object lesson about demagoguery and fear.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention here that my own institution was subjected to a state legislative investigation/witch hunt, and dismissed three tenured faculty in 1948, mostly for failing to cooperate. The firings of Herbert Phillips, Joe Butterworth and Ralph Gundlach gave the University of Washington a black eye and eased the way for similar indignations elsewhere and is a tender subject in some quarters to this day.

Of course, we’re all smarter now, more experienced at critical thinking and separating truth from fiction. So it couldn’t happen again. We’ve all learned from our mistakes, and know better than to trust any person, or organization, or government, that claims to have a list of bad people or bad ideas. If only.

It seems only fitting to give the last words to Edward R. Murrow, whose See It Now program in March 1954 dissected and furthered an already sliding opinion of McCarthy and his tactics. By November of that year, he’d be condemned by the Senate; that seemed to break him and by May of 1957 he was dead, likely of alcoholism, aged 48. Murrow’s broadcast ended thus: “The actions of the junior Senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad, and given considerable comfort to our enemies. And whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn't create this situation of fear; he merely exploited it — and rather successfully. Cassius was right. ‘The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.’”

References

American Business Consultants. (1950). Red channels: the report of communist influence in radio and television ... New York: Counterattack.

Fried, A. (1997). McCarthyism: the great American Red scare : a documentary history. New York: Oxford University Press. Herman, A. (2000). Joseph McCarthy: reexamining the life and legacy of America’s most hated senator. New York: Free Press. Joseph McCarthy. (2014, June 20). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Joseph_McCarthy&oldid=613344817 Leviero, A. (1954, December 3).

Final Vote Condemns McCarthy, 67-22, for Abusing Senate and Committee; Zwicker Count Eliminated in Debate. The New York Times, p. 1. McCarthyism. (2014, June 19). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=McCarthyism&oldid=612963888 Reeves, T. C. (1982).

The life and times of Joe McCarthy: a biography. New York: Stein and Day. Schrecker, E. (1994). The age of McCarthyism: a brief history with documents. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin’s Press. Seeing Red. (n.d.). Retrieved June 20, 2014, from http://www.washington.edu/alumni/columns/dec97/red1.html