John Snow's Cholera Map, 1853

Making sense of big data, way back in the 19th century.

Transcript

The year is 1854, and you’ve been sent on a simple errand. Your family needs water, and so you make your way to one of the neighborhood water pumps—the pump closest to your house. You fill a bucket with water, and return home. You don’t know it yet, but in choosing to use that particular pump, you’ve just determined whether your family will live or die.

Introduction

This is the story of the English physician John Snow and the map he created during a devastating cholera outbreak in London in 1854.

On the one hand, it’s a complicated story, inhabited by mysterious, microscopic organisms, a young and crowded metropolis strangled by dung heaps that stood as tall as houses, and factions of scientists and civic leaders at odds over how to eliminate an invisible killer. On the other hand, it’s a very simple story.

It’s a story about death. In Victorian London, lives hung in a delicate, unfair balance. Your life, and the lives of everyone you loved, depended on where you got your drinking water. You lived or died by the simple choices you made—choices we make fearlessly today. If you chose the water pump to your right, your family lived. If you chose the water pump to your left, your family is dead by dawn, their bodies suddenly, mercilessly emptied by cholera.

This is also a story about birth—the origins of the present-day metropolis, the emergence of modern epidemiology, and the ancestors of John Snow’s cholera maps that foreshadowed information systems, like GIS, that allow us to analyze, visualize, and understand the patterns and trends that affect our lives.

Snow’s use of mapping is the contemporary equivalent of Google Maps or social-networking sites, like Yelp, that allow users to enhance existing maps. Just as we use Google Maps and Yelp to record where we’ve been and what we’ve experienced, Snow added layers of local and personal knowledge to available maps in order to tell the terrible story of an epidemic.

Ultimately, this is the story of a document that changed the world by giving voice to a life- saving idea. Like all good maps, Snow’s map inspired a journey. In illustrating the patterns created by a devastating epidemic, he opened the eyes and minds that would eventually subdue the killer named cholera. Snow’s map gave Victorian England exactly what it was looking for— a way out.

Cholera is a terrible way to die. It arrives unseen, unannounced, and then kills with cruel and baffling speed. Snow’s contemporary, the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, lamented cholera’s ability to “catch” a person with “cramps” and “spasms” that turn gentlemen “dead-blue.” A clinical description explains the cause of these deadly contractions: cholera is a severe intestinal infection caused by ingesting food or water contaminated with the cholera bacteria.

The Killer Cholera

The bacteria cause the body to expel a profuse amount of watery diarrhea that leads to a sudden, lethal state of dehydration. Just imagine: your child, husband, or wife complains of a stomachache. In the few minutes and hours it takes to fetch relief—the comfort of words, water, or a doctor—you witness your loved one vanish. Cholera can cause a person to lose up to thirty percent of their body weight in a matter of hours.

Death is only the beginning for cholera. While cholera demands a lot from its victims, it requires little to multiply. The discharge caused by cholera is colorless, odorless, and contains a large amount of the cholera bacteria; all it needs to spread is an environment in which people frequently ingest other people’s waste.

In 1854, London was the world’s most populous city, with two and a half million people. For all the marvels it contained—like the Crystal Palace—London lacked public-health departments and sewage removal technology to effectively manage the waste generated by a city that would be considered dense even today.

This resulted in overflowing cesspools that forced the river Thames to serve an ill-fated, dual purpose—acting as both a main source of water and a sewer system. This made John Snow’s London the perfect host city for an infectious disease.

So, what does a cholera map look like?

The Map Itself

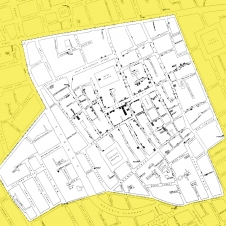

I’m staring at the map John Snow published in 1855—or at least a digital reproduction of it found on UCLA’s Department of Epidemiology website. This map documents the grim footprint left in London’s Soho neighborhood during an outbreak that occurred there in 1854.

As with most maps, I see street names and points of interest, like Golden Square and Piccadilly Circus. I also see hash marks rising, in varying heights, from the straight edges formed by streets. It’s easy to imagine these lines representing some kind of score, and it’s obvious that, regardless of who is winning or losing, all the action is emanating from a dot labeled “pump” sitting at the point where Broad and Cambridge streets meet.

Without knowing anything about cholera or London, I can see that something monumental happened at the corner of Broad and Cambridge.

Which is true. The water pump sitting at this corner drew its water from a source contaminated with cholera. The towers of hash marks do represent a score--they tally the lives claimed by cholera. More than five hundred people died within two hundred and fifty yards of this water pump within a ten-day period.

At the time, Snow was a noted physician, celebrated for his pioneering work with anesthetics. Snow had mastered the use of chloroform, and this breakthrough brought much-needed relief to Londoners undergoing medical procedures. His work was so respected that he was called upon to comfort Queen Victoria, administering chloroform as she gave birth to her eighth child. Snow’s professional success allowed him to pursue a personal obsession: solving the riddle named cholera.

By the time John Snow mapped cholera’s impact on Soho, it had been killing Londoners for several decades. It wasn’t uncommon for an entire family to be killed by cholera within a two- day period. People were dying, and there were many scientists joining Snow in trying to answer the anxious question: “why?” Some proposed that cholera was caused by foul air emanating from London’s graveyards. Others suggested it was linked to atmospheric conditions. It even seemed possible that the disease was a poison leaking from the earth itself.

Overload and Clarity

These theories were variations on the dominant worldview of the time known as the “miasma” theory. Miasmists believed that disease was caused by harmful mists and vapors that arose from filth.

Given how filthy Victorian London was, it’s not surprising that many of the most powerful people in London—members of Parliament, clergymen, and city commissioners—embraced the miasma theory.

What is striking is something that can be hard for us to imagine today: in 1854, Londoners were suffering from information overload. Each theory about cholera had its own proponents, supported by streams of data recorded and disseminated in newspapers, dot maps, monographs, and lectures. Victorian England was home to an information revolution, with demographers recording births, marriages, weather, air quality, and, for the first time, tallying deaths by cause, location, age, and occupation. If you knew how to assemble the pieces, the patterns affecting British society—the ebb and flow of birth and death, cause and effect, illness and prevention—came into view.

John Snow used the tools available to him at the time, assembling the pieces and solving the mystery of cholera. And he did it with a map.

Based on what he learned from studying a previous cholera outbreak in London, Snow developed a theory that cholera was transmitted by water. He arrived at this theory after examining the relationship between cholera deaths and sources of water in South London, where he found that far more people were killed by cholera in households that received water from a supply that mingled with sewage.

Map Details and Predecessors

The Soho outbreak struck close to home—Snow lived and worked near the Broad Street water pump. In creating his famous cholera map, Snow wedded raw data—including the mortality rates recorded by the local registrar—with street-level knowledge of the patterns and habits of his neighbors acquired through observations, interviews, and being part of the neighborhood. Snow knew which pumps individual families were known to drink from, and he knew the distance between the homes of those who died and the different water pumps they might have used.

Snow distilled all of this information into graphic representations of life, death, and water sources. The hash marks, street and building names, and dots noting the location of water pumps were placed on top of an existing map that had been produced by C.F. Cheffins, a surveyor and mapmaker.

The result is a map that paints a clear picture of how cholera travels through a community. The result is a map that scientists, scholars, and writers still, to this day, consult for direction. Writer Steven Johnson notes that “part of what made Snow’s map groundbreaking was the fact that it wedded state-of-the-art information design to a scientifically valid theory of cholera transmission.

Geographer Tom Koch and statistician Edward Tufte both admire the pictorial aspect of the map, which resulted in placing data in the right context for considering cause and affect. In being so selective about what information was included—the street names, breweries, workhouses, and water pumps—the map revealed an overwhelming connection between the Broad Street pump and cholera transmission. In tallying cholera deaths while also showing the location of the area’s other water pumps, the Broad Street pump was shown standing at the epicenter of the epidemic.

This map was born out of Snow’s previous attempts to condense and communicate his waterborne theory. Snow created a map during his South London study that featured hand- inked dots, which were hard to read, and cloudy colors that tried, but failed, to show the connection between cholera deaths and water sources. Snow also published a table to tell the same story. But it wasn’t quite right. It lacked key pieces of information gleaned later through interviews and observing the patterns of daily life in Soho.

Snow corrected such errors in producing his 1855 map, which turned out to be a document that could tell a story that a table or previous maps could not. It was a document that changed the minds of individuals who went on to change policies that transformed city living from a death sentence to a sustainable and life-affirming existence.

Given the effect this map has had on urban life, cartography, and science, you may want to know where the map is today. If any original copies of the map exist, no one seems to know, or care. Which doesn’t mean the map is hard to find. Authentic copies of the map are found on university websites, in textbooks, and popular science books. But the whereabouts of an original copy appears to be unknown. When it comes to determining the value of Snow’s map, it seems that the information contained in the map is more important than the document itself.

Map Reflection

What is it about a map that enables it to communicate a scientific breakthrough when other documents or forms of communication—indexes, lectures, monographs—can’t? What is it about a map that allows it to leave an indelible stamp—a lasting idea—on society long after the map itself has decayed or been junked, recycled, or lost?

The power contained in a map lies in its ability to provide sure footing in the midst of unknown territory. In providing direction, a map complements the imagination: it tells us where we are, where we are going, and where we we’ve been. Snow’s creation demonstrates that maps provide more than simple directions—they can also provide much-needed clarity.

I’m looking at Snow’s map, and the neighborhood I see is a place that can no longer be visited. Soho, as represented in this map, does not exist anymore, just as the world depicted in this map doesn’t exist anymore. Today, Broad is now called Broadwick Street, and Cambridge is now Lexington Street. Today, we know how to prevent and treat cholera, and how to build healthy, sustainable cities.

We may not be able to use this map to travel through present-day Soho. Instead, we can use it for something even more meaningful. We can use this map to return to the exact corner where the world changed.