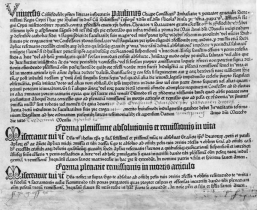

Gutenberg Indulgence, 1454

What Gutenberg printed first, the unexpected effects his works had, and the lucrative business of printing indulgences.

Transcript

Wouldn’t it be great if everybody had a get out of jail free card? We’ve all been there, done something we regret or wish we hadn’t, or gotten ourselves into a situation we’d love to undo. Second chances aren’t impossible—ask Marion Barry, or Charlie Sheen—though of course there’s no guarantees. People are often willing to forgive and sometimes to forget, but the idea of a ticket that could wipe the slate clean is very attractive indeed.

Actually, in the right circumstances, this isn’t out of the question. You’ve got to mean it, you’ve got to do something to earn it, and you’ve got to be Catholic, but there is a way to get a redo, and for a long time a simple piece of paper, or parchment, would do the trick.

Something like that can not only buy you out of a heap of sinning; in sufficient quantities it can also lead to the transformation of an entire continent.

Gutenberg. Bible. We’re so used to hearing those together, that many people likely haven’t thought much about what else he might have done. Yes, he invented printing using movable type in Europe, everybody knows that; maybe somewhat fewer know he pioneered oil-based inks or the wooden screw printing press.

Gutenberg himself is, in large part, a cipher. There are large chunks of his life we know nothing about, leading some to wonder if it was really him at the wheel, so to speak. We know his father worked at a mint and he had experience as a goldsmith; we also know that he was either a terrible businessman or really unlucky. Or both. He and others wanted to make money by selling mirrors for use in a holy festival, only to have it postponed by a year because of flood or plague or something. Now, stuck with a bunch of unsellable mirrors, he says he has a great idea that will turn around their fortunes.

He started work on the bible in 1452, amidst a series of loans from one Johann Fust, (who later sued him, claiming no interest was paid and the money misused) who bankrolled the scheme. Within 3 years, the time it would take to produce one bible by hand, the work is done. A total of 180 were printed, of which 48 complete examples are known to have survived. They’re trophies for collectors and institutions; even having a single page, or “leaf” is a point of pride.

It appears that two presses were used, with different sets of type, as many as 100,000 separate pieces in all, along with paper and the skins of 3,200 animals for the 40 vellum copies. They were even customizable; if you bought one, you could have your own decoration added in spaces intentionally left blank. Voila—chalk up another one for Western civilization.

Except there’s more to the story. The bible is universally known as his masterwork, but while that was in the works, there was cash to be made, producing schoolbooks, calendars, and especially in the lucrative business of printing indulgences. These had been around for centuries, an opportunity for the faithful to atone and have their sins remitted by, say, good works, making a pilgrimage, fasting, going on Crusade...or money. The document itself is just a form, boilerplate we’d say today, with spaces for the name, date and seller. Take that to your confessor, in a state of grace, and you’ve gotten yourself out of Purgatory. This was big business for everybody involved, for the printers but mainly for the church; print runs ran into the thousands. In one case at least 190,000 were printed.

There is some evidence that Gutenberg produced indulgences as early as 1452, though the earliest one to survive is from a series printed in 1454--the earliest Western printed document with a date. That one was created to raise money for the defense of Cyprus from the Turks, who had just taken Constantinople the previous year.

Gutenberg’s legacy is obvious—the printing processes he pioneered spread within decades, helping to nourish the emerging Renaissance and Enlightenment that led Europe out of the Middle Ages.

Some 60 years later, though, a German priest got fed up with the latest abuses of the indulgence system, now made so easy by the new technology. This time it was to raise money for the building of St. Peter’s. Fed up enough to make his points, all 95 of them, to his bishop. Those theses, we think intended for private discussion, went viral. They quickly got printed, though we don’t know how or by whom. So were later sermons and broadsides with demands for change—a format that helped to lead to the development of newspapers—and bibles in German, which helped to coalesce the language. Oh, yeah, and kickstarted the Reformation, making Martin Luther another central figure of the previous millennium.

There’s yet one more aftermath to this story, though, which has resonance for us today. Both the indulgence and the bible were printed with fonts that make them look very much like their handwritten, manuscript predecessors. This makes sense; if you want something new to be adopted, making it look familiar, as much as like an old version as possible, can be very helpful. Things like this are call “skeumorphs,” and they’re still around. That’s why word processors still use “cut” and “paste” metaphors, and why cell-phone cameras often make a clicking sound like a shutter when there’s no mechanism at work at all. Or why electronic books, so far, try so hard to resemble their print counterparts.

It wasn’t long before new type styles and formats and illustrations made an appearance. These first bibles also have no page numbers, indentations, or paragraphs; these devices we take so for granted in books today were yet to be widely adopted. Books printed in the 15th century are called incunabula, from the Latin for “cradle.” Very apt. Gutenberg and the other early printers were responsible not only for the birth of a new way of making copies faster. They were at the very beginning of a long road of figuring out what a printed book or a printed anything would be, what it would look like, and over the centuries those have grown in ways that medieval copyists couldn’t imagine.

Printing also typically led to higher levels of education and literacy, a movement to censor uncomfortable works, and the development of national literatures and cultures. Now, as books evolve yet again, their future forms and impact is similarly unknown.

Brian P. Smentkowski & Michael Levy. (n.d.). Nineteenth Amendment. Encyclopedia Britannica.

References

David E. Kyvig. (1996). Explicit and Authentic Acts: Amending the U. S. Constitution, 1776-1995. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Eleanor Clift. (2003). Founding Sisters and the Nineteenth Amendment. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. National Archives. (n.d.). Constitutional Amendment Process.