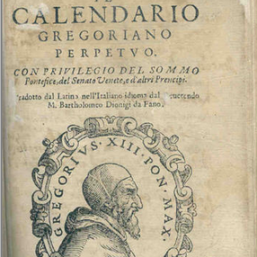

Gregorian Calendar, 1582

A story of power, precision, faith and…wait for it…crowdsourcing.

Transcript

A document that changed the world:

Gregorian Calendar, a papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII 1582

How long is a year? Today, we know it’s 365 days, sort of. Hundreds or thousands of years ago, though, knowing how long a year was, when the sun would rise over a particular hill, when a star would be in the right position, really mattered, so that you knew when it was time to plant or worship a particular god.

How long is a month? That one’s a little harder, some are 30 days, some are 31, February’s different, but in ancient times, it’s actually easier. You can see a month right up in the sky, as the moon waxes and wanes over the course of 29 days or so. In fact, There’s a prehistoric bone fragment etched with what might be a lunar cycle, one of the first examples we have in writing. Days are even easier.

The problem is, even though we can reckon the days and the months and the years independently, trying to make them work together is really hard. The year isn’t exactly 365 days, it’s more like 365 1⁄4, actually 365 5h 48m 46s for those playing along at home. And a lunar cycle of 29 days, which is really closer to 29 1⁄2 or so, and changes over the course of the year, doesn’t divide evenly into 365 or 365 1⁄4. The moon and the sun don’t play all that well together, which leads to some serious challenges if you’re trying to build a way of recording time that takes account of both the moon and the sun. Now we take for granted that all this has been sorted out, but it’s a subtle, difficult and important problem, potentially as important as your eternal soul, and the question is, who gets to decide?

This is a story of power and precision and faith. Trying to figure out a way to make sense of the years and the months goes back to the dawn of human history. The Egyptians had a functioning calendar at least 6,000 years ago, and Ptolemy III added a leap day every four years in 238 BCE; the current Mayan calendar is at least 2000 years old. Caesar took a crack at solving the calendar problem and got it nearly right, in the process giving us several of our current month names including July for himself.

There’s long been a sense among people who paid attention to such things that something about the calendar wasn’t quite right. There were a number of attempts to understand and fix this over the centuries in the West, but as learning and science faded during the Dark Ages, those got weaker and feebler; as other parts of the world, particularly the Islamic world continued to make progress.

The primary motivator for this, in Christian Europe, was figuring out the right date for Easter. Caesar’s calendar, good as it was, assumed a year that was just a little too long, by about 11 minutes. That doesn’t sound like much, but as the decades march on, it adds up. Easter, ever since the Council of Nicaea in 325, is the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, which is tricky enough, but if your year is too long, eventually the vernal equinox starts to creep earlier and earlier. Get the equinox wrong and Easter is wrong, and celebrating Easter on the wrong day, as people were increasingly concerned could happen, could imperil your chances for salvation.

The process by which this got resolved is a fascinating combination of the medieval and the modern. Things were finally coming to a head in the late 16th century, as Pope Gregory XIII, who devoted much of his papacy to reforming the church, sending missionaries far and wide and furthering the Catholic faith, realized that something had to be done. The modern part, sounding very familiar to our ears, was the commission he convened in the 1570s to come up with a solution. They made a report with a series of recommendations to correct the drift that had accumulated over 1600 years and to prevent the calendar from going astray in the future. Those recommendations were sent to universities and the crowned heads of Europe for commentary. And they got it— dozens and dozens of responses came in, many simply signing off on the proposals, some suggesting revisions and others thundering disapprovals on grounds both scientific and religious.

One idea that did get traction was a calendar that would simply count the consecutive days from a fixed historical point, without concern for months or years. Impractical for everyday life, this Julian date calendar has been adopted by astronomers and some computer operating systems for its ease of use, counting from noon on 1/1/4713 BCE. If you wanted to start using this, the Julian date for 1/1/2012 is 2455927; make a note.

In any event, the feedback came in, tweaks were made, and here’s the medieval part. The pope, in all his regal splendor, signed, on 2/24/1582, a bull (from the Latin bulla, the clay or metal seal attached on a document). Papal bulls take their titles from the first two words in Latin, in this case “Inter gravissimas”, “among the most serious tasks of our pastoral office...” It was posted on the doors of St. Peter’s on March 1, and around the city, copies sent to every Catholic country by papal ambassadors. Even more medievally, it prohibited unauthorized publication of the calendar or associated documents on pain of fine or excommunication. Imagine how well that would go over today.

It established the system we still use today, called now the Gregorian calendar, with a year of 365 days, a leap year every 4 years except multiples of 100 not also divisible by 400, so 1900 wasn’t a leap year and 2100 won’t be, but 2000 was. It realigned the calendar, established January 1 as the first day of the year, and most critically corrected the overshoot of the previous calendar by decreeing that October 4, 1582 would be followed by October 15, eliminating, with the stroke of a pen, 10 days.

You can imagine the kind of confusion that would happen as a result of that. What to do about deadlines, taxes, interest payments, shipping schedules? Birthdays? Prison sentences? Saints days? A riot in Frankfurt erupted, based on the belief that the pope was trying to steal days away from people’s lives.

The calendar was not an immediate, universal hit. To be honest, the papacy wasn’t what it used to be, so what might have been accomplished by unquestioned fiat just a century or so previously now took some work to achieve. A few reliably Catholic countries went along immediately: Spain, Portugal, Poland, Italy. Others moved a little more deliberately; France and Hungary took a few years longer. But recall this is the late 16th century, a time of great religious upheaval, and we’re only now 65 years after Luther posts the 95 theses. The Counterreformation is moving into high gear, less than 20 years after the Council of Trent condemned Protestantism as heresy. This didn’t help matters in trying to get, say, Lutheran Germany to go along with anything, much less slicing days away.

So this became a highly political and politicized document, not well taken in Protestant Europe. That first sentence in particular was a problem, since those most serious duties it talks about are following up on the dictates of the Council of Trent. On it languished; most of Germany didn’t adopt the Gregorian system until 1700, England not until 1752, and other parts of the world much later, including Russia in 1917 and China not fully until Mao in 1949. Indeed, the religious calendars of Judaism and Islam have never adopted the solar system. The Islamic year is purely lunar, consisting of about 354 days, and thus continually floats against the Gregorian year, explaining why the holy month of Ramadan comes a few days earlier in the Gregorian system each year.

In thinking about all this, one wonders who could do this today? What single person could, by virtue of their position, establish a new calendar with any hopes that it would be broadly or universally adopted? Certainly not the pope, and there’s no Roman emperor around any more, so who else is in a position to effect change beyond the boundaries of a single nation?

It would have to be, today, an international organization, the UN and one of its shadowy, obscurely named agencies, but it would have to be the result of broad consensus and even then, somebody wouldn’t be happy about it. The idea that a single person, any single person, could, with the stroke of a pen make that sort of profound change, seems completely impossible to us today. It’s simply not that sort of top-down world any more.

But curiously, as the power of any individual person has diminished, the power that a document could have, might in fact have grown. It’s farfetched to think that a new calendar proposal—and there a number of them out there—might take off or go viral and be adopted bottom up, but it’s not totally out of the question if it caught the popular imagination in the right place and the right time. It’s a bottom up world—ask the open source software community, the Occupy movement, or the folks who built and maintain Wikipedia. So perhaps, in the modern world, the power of the document might be greater than the power of the person.

Bill Spencer. (2002). Inter Gravissimas. http://www.bluewaterarts.com/calendar/NewInterGravissimas.htm

David Ewing Duncan. (1999). Calendar: humanity’s epic struggle to determine a true and accurate year. New York: Bard.

The calendar reform | Official website Lux in arcana - Vatican Secret Archives reveals itself. http://www.luxinarcana.org/en/documenti/curiosita/la-riforma-del-calendario/