Exaltation of Inanna, BCE

What does it mean to be an author? Let’s go back 4,000 years to examine one wildly creative high priestess’ job to find out.

Transcript

A document that changed the world a hymn, now known as the “Exaltation of Inanna”, composed by the high priestess Enheduanna, in the Sumerian city-state of Ur around 2300 BCE

What does it mean to be an author? That probably sounds like a stupid question: have an idea, put a bunch of words in together in order that makes some sense (though I bet we’ve all read stuff from “authors” who did none of those things), maybe find a way to get somebody else to listen or read, and bingo bango bongo, you’re an author. More seriously, “authorship” also typically connotes creativity, productivity, inventiveness and originality.

My fellow-travelers in the library field, those intrepid catalogers who design precise tools to find just the right work in an ever-growing, if not wine-dark, sea of the human record, prefer the term “statement of responsibility” to denote authorship, and while that sounds bureaucratic and a bit weird, it resonates. An author is responsible for a work, and if you think about it, in two different ways: responsible for it being created, and responsible for what it says, no matter how long it survives.

One author did even more. She not only was responsible for a series of works, which have survived a very long time, she may also be responsible for the idea of being responsible. She may be the origin of the idea of authorship itself.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School, and in this episode we’re going way back, about as far back as we can go. Enheduanna’s father was Sargon, who one source referred to as a “charismatic usurper” and who united a number of city-states into the first Mesopotamian empire. This didn’t go over universally well, so in a savvy move, he appoints his daughter to be a high priestess, to calm the waters and solidify his position. Whatever she did, it worked, and the high priestess job stayed with princesses for another 500 years. And her job became her name; “en” means high priestess, and Nanna was the moon god.

It’s remarkable that we know this much about a woman who lived over 4000 years ago in what is present-day southern Iraq, at the same time as the Old Kingdom in Egypt and the rise of maize and pottery in Mesoamerica, at roughly the middle of the Bronze Age in Europe.

It’s even more remarkable why we know so much about her, which is primarily through her writings. She produced a quite impressive body of work, including a series of hymns dedicated to temples, a number of other works known to us in fragments, and the best known, a 153-line hymn which has no known title of its own, but which has been designated by modern scholars as the “Exaltation of Inanna”. Inanna was the Sumerian Queen of Heaven and goddess of love, related to the Akkadian Ishtar, and in the hymn, Enheduanna praises her, and then asks for her help and, moreover, vengeance, in reclaiming her position and home after being exiled due to some unknown political disturbance. It ends triumphantly with her return. It’s quite affecting, even today. Here’s a sample; my Sumerian is a little rusty, so forgive the pronunciation.

“When mankind comes before you/In fear and trembling at your tempestuous radiance/They receive from you their just deserts.”

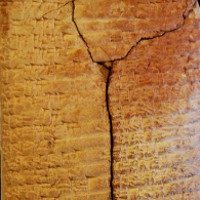

This has come to us in multiple versions; the major translation in 1968 lists at least 50 manuscripts on clay tablets, including some from several hundred years after its composition, so it seems that this hymn survived and was important for a long time. We also know her from an limestone disc showing her in worship, now at the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

Let’s put this in a bit of context; the origins of writing are a bit murky, but it’s safe to say that people were writing purposefully by about 3000 BCE, and the oldest “literature” is about 2600 BCE. This puts the Exaltation among the very first works we know, a little earlier than the first parts of the Epic of Gilgamesh, 500 or so years before the Code of Hammurabi and the Rig Veda, 700 years before the Egyptian Book of the Dead, more than 1000 years before the I Ching, and 1500 before the Iliad and Odyssey, and the Hebrew Bible. In other words, this is really old, among the oldest things we actually have.

Many sources describe Enheduanna as the “earliest known author”, and also coincidentally one of the earliest women in history whose name has survived, though without any citation or definitive—dare one say authoritative—source, and then move on to tell her story, of her political/social/religious impact and importance, describe the works, and so on. What I find stunning is how that completely breezes past the most extraordinary aspect: the first known author! Even if she’s not, which is nigh impossible to be conclusive about that, not to mention new archeological evidence could always come along to dislodge her claim, let’s not bury the lead here. Somebody had to be first of thinking of recording “I wrote this” and she may well have been that person.

The idea of writing, of taking credit, of authorship, is so deeply ingrained, so common now, it’s difficulty to fully appreciate how profound its development is. As I said, authorship comes with responsibility, for the writing itself and also the ideas and the results of those ideas. In the contemporary world, authorship also brings rights in the form of copyright and the opportunity to protect the ways in which expressions of ideas can be copied, shared, and used, including potential monetary reward. More deeply, there is credit, and blame, to be had, for works noble and toxic and everywhere in between.

And, names matter; we use author names in many settings such as libraries and bookstores, to bring together a body of work, because that’s often what people are looking for; works that are anonymous or pseudonymous often engender curiosity about who “really” wrote it, which can even migrate to contempt when a well-known author like Stephen King or J. K. Rowling writes under another name, as though somehow that’s not fair or appropriate.

A couple of last notable aspects here. One is the overt nature of the creative process in the Exaltation. There’s an section of the hymn that explicitly describes its own composition, in a maternal way: “I have given birth,/oh exalted lady, to this song for you.” which seems somehow very contemporary. As does this: who hasn’t been fired, or heartbroken, or feel like the world was out to get you? “I am placed in the lepers’ ward/the light is obscured about me/The shadows approach the light of day,/My mellifluous mouth is cast into confusion/My choicest features are turned to dust.” And wanted to even the score? “This city--/May it be cursed.../May its plaintive child not be placated by his mother!” After something like 200 generations, her bitterness, pain, and satisfaction in her ultimate victory ring very true to modern ears.

Throughout the poem, Enheduanna uses the first person, and twice refers to herself by name. In the process of speaking to her goddess she also speaks to us, in her own voice from a time so long ago we can barely imagine it. By impressing marks in tablets of clay first wet, then baked, she recorded her faith, her hopes, her fears, herself. For dozens of centuries those tablets went unread and unremembered until they were rediscovered and translated, and so Enheduanna speaks to us again, and still.

Enheduanna. (1991). In Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World.

Enheduanna. (2014, May 24). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from Enheduanna. (n.d.). Retrieved May 29, 2014, from http://www.cddc.vt.edu/feminism/enheduanna.html

Feldman, M. H. (2008). Enheduanna. In Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History.

Hallo, W. W., Dijk, J. J. A. van, & Enheduanna. (1968). The exaltation of Inanna. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Leith, M. J. W. (2005). Gender and Religion: Gender and Ancient Near Eastern Religions. In Encyclopedia of Religion.

Melville, S. C. (2004). Royal Women and the Exercise of Power in the Ancient Near East. In A Companion to the Ancient Near East (pp. 219– 228).

Blackwell. The exaltation of Inana (Inana B) from The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. (n.d.). Retrieved May 29, 2014, from http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.07.2#