Egyptian 'Book of the Dead', BCE

The ancient text is a repertoire of about 200 spells meant to assist the newly departed soul in its perilous travels to get to an afterlife of comfort and plenty.

Transcript

Can we please just stop and ask for directions? I know, it’s a cliché, and less relevant in our modern world with sophisticated GPS, digital mapping tools and apps, and so on, but it wasn’t so long ago that road maps and atlases and helpful gas station attendants were vital parts of making your way in new or unfamiliar territory. And guides of all sorts, from books to websites to word of mouth on social media, can also help to clue travelers in to local customs and lingo.

There’s one journey, though, that everybody takes sooner or later, but nobody comes back to tell us how it’s going; the ultimate journey, to “[t]he undiscovered country from whose bourn/No traveler returns” as Hamlet has it. The desire to know, and be ready for, what awaits us there, and moreover how to get there safely, has occupied a great deal of human thought and also yielded a work of exacting detail, surprising flexibility, and just the right word at just the right time.

A document that changed the world: “The Book of Going Forth by Day”, known more commonly today as “The Book of the Dead”, a set of spells and images from Egyptian funerary equipment, by about 1600 BCE.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. The Book of the Dead was having something of a cultural moment in the late ‘70s when I was growing up, occupying much the same territory as horoscopes, crystals, amulets, tarot cards, auras, seances and the like. I think it’s the name, which you gotta admit is really cool, even if it’s made-up 19th century German. The culture, religion and mystique of ancient Egypt has fascinated for millennia from the Romans to today with TV shows still trying to figure out who or what killed King Tut, umpteen mummy movies back to 1899, Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra (may Isis forgive us), “Walk Like an Egyptian” and even the staggeringly awful Gods of Egypt movie. There’s something compelling, dare we say spellbinding, about their civilization, art, and mythology. Think about it – why is the Washington Monument an obelisk of all things?

What we now know as the “Book of the Dead” is many things, but it’s not a book in any contemporary sense of the word. It’s better described as a corpus, a repertoire of about 200 spells meant to assist the newly departed soul in its perilous travels to get to an afterlife of comfort and plenty. It’s part of a genre called “mortuary literature” and has its origins in earlier forms, starting with Pyramid Texts as far back as 2300 BCE actually written on the walls of royal pyramids, sometimes with intentionally mutilated characters to prevent harm; these evolved into Coffin Texts, so named because they were written on the insides of coffins.

Around 1700 BCE, sarcophagi changed from rectangular to more human shapes, which might have left less room for interior writing, and that might have led to the adoption of papyrus, a writing material already in use for over a millennium, yielding the plentiful examples we now know of. Over time, these too evolved, from the hieroglyphic writing we associate with Ancient Egypt to the more readable hieratic script and the increasing addition of images which were equally potent in achieving the desired effects. These papyri survived in large part because the dry desert climate helped to preserve them, though there are examples stained with, um, fluids from the mummified remains they were buried with, often placed in direct contact with the bodies, presumably for easy access.

The Egyptians believed that the only way to Duat, the underworld, was through the tomb, and that rituals both in life and in death were necessary to get there. The newly-deceased would have to make a perilous journey, passing through a series of gateways or portals guarded by fearsome beasts, demons, and gods, and facing a number of challenges and questions along the way, requiring precise and correct answers at each stage, which the spells were meant to provide, so having them at the ready was critical in making it through successfully. Spells could protect you against dangerous animals, allow you to breathe or drink, or transform your physical form as necessary, reflecting their belief in magic, the power of both the written and spoken word.

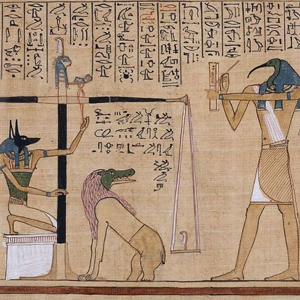

After employing dozens of these preparatory and protective spells, providing detailed intel on the specific names of gates and their guardians, the deceased would arrive for the Declaration of Innocence at the Hall of Two Truths, facing a panel of 42 judges presided over by Osiris, god of the underworld. Here Spell 125 would have you covered, so you could correctly name each of the assessors and perform the Negative Confession, swearing your innocence to a long list of possible sins and crimes, including murder, blasphemy, cruelty, profiteering, adultery, impatience, tampering with weights or slaying sacred cattle. At this point, your heart, which they saw as the essence of a person and the seat of mind and intellect, which would remember what you did in life, would be weighed against a feather representing truth; one of the most-discussed spells, number 30, directs the heart not to rat you out, literally not to make your name stink, which could come in quite handy indeed for many of us. Failure at any stage meant an eternity of isolation, dishonor and degradation, including the eating of excrement (ewww), perpetual thirst, or being thrown into a lake of fire or devoured by wild beasts. Passing the test on the other hand led to paradise, a bountiful and successful afterlife, filled with eating, drinking, sex – and work, though burial figures known as ushabti would handily come to life to do that for you.

Now, here’s the thing that gets me. This has got to be the highest stakes journey you could imagine, one wrong move or word and it’s the dunghill for dinner forever. And there’s lots of redundancy in the system, in addition to spells on the walls and insides of sarcophagi, there are examples on leather, stelae, even on the mummifying linen bandages themselves so the deceased would literally be wrapped in the spells; others are intended to be inscribed on scarabs or magical bricks. But – and this is a pretty monumental but – of all the many examples which have been studied, no two appear to be identical.

There is, apparently, no canonical or definitive version; each person – and let’s be clear that this is an elite and exclusive practice reserved for people who could afford it all, maybe 10% of the population at best – got to pick their own from an evolving corpus of options and possibilities. There are commonalities and patterns, to be sure, but there is great variation in content and length, ranging from scraps with a handful of spells to scrolls up to 40m in length. The choices of which spells to include and in what order appear to be purposeful and carefully considered, rather than merely random, though it’s unclear by which criteria these decisions were made, economic perhaps, or personal preference? I have to say, for something this important in a culture so fixated on a successful afterlife as well as the peace of mind of the living, it’s astonishing that some of these practices seem idiosyncratic and apparently that was not only ok, but more or less the norm.

Scrolls were probably created in temple scriptoria by teams of professionals, some of whom focused on images, others on text, not entirely unlike some modern comic books or graphic novels; scholars estimate a good quality version could be produced in a week or two, though the quicker option for your dearly beloved on the go is a more or less off-the-rack version, with spaces left for names to be written in, including some instances where the characters needed to be stretched out or squeezed in to fit and even some with the names still blank which might have caused some red faces in front of Osiris. A “decorated” one might cost you the equivalent of a half year of a workman’s wage, or the price of 3 donkeys.

A typical scroll often has a blank papyrus sheaf attached to the outside for protection, is 20-40cm wide, and highly structured, primarily using black ink, with red for headings, openings, and names of dangerous animals; there are regular margins, framing lines, and fields for images which were increasingly prevalent over the centuries, so we know that great care was taken with these though little evidence of practice or training versions has been uncovered, and master copies are quite rare. The practice continued through several periods and dynasties, eventually starting to fade out by the turn of the Common Era as the Greeks and Romans entered the scene.

We owe that super cool name to Karl Richard Lepsius, described as the founder of German Egyptology, who apparently named it “Tötenbuch”, perhaps from the Arabic term used by villagers to describe tomb papyri. I won’t attempt the name by which the Egyptians knew it, translating roughly into “The Book of Going Forth by Day,” reinforcing that the soul isn’t trapped in the tomb, can move, and go into the daylight as they so fervently hoped. Lepsius published the first translation with the still-used numbering system in 1842, followed by comparative edition by the Swiss scholar Edouard Naville, who crafted a more or less “complete” version of each of the many dozens of spells, with variations. This work took nearly 10 years, supplemented by vignettes drawn by his wife Marguerite [Naville]. At first, spells would have been drawn or transcribed for publication by hand, using tracing paper; then a metal movable type set was created. Now, as you’d expect, there are digital fonts, and hieroglyphic characters have their own Unicode points, created in 2009, nestling right between Cypro-Minoan cuneiform and Anatolian hieroglyphs. Research continues; the most recent complete version, the first in a century, was found in 2022 at the Saqqara necropolis near Cairo.

It is possible – that they had it right, and those who survived the beasts and labyrinths and judgment are enjoying the fruits of the bountiful and eternal afterlife they anticipated. We tend to think of ancient Egypt as unchanging, stable, as rigid as the poses in their paintings and as monolithic as the pyramids and obelisks, and, let’s be fair, the pharaonic period endured more than 10 times as long as the United States has. Yet not only did this practice evolve over a couple of millennia, they were remarkably flexible about the specific form.

Many writers compare the Book to a travel guide, which is fine, though I would also suggest it’s an odd hybrid – not unlike a crocodile-headed god, with a password manager or better still those little post-it notes you’re not supposed to have next to your computer that remind you of what codes you need to access what, equally valuable in navigating the traps and pitfalls of the modern world.

When your time comes, I might suggest you could do worse than start with Spell 9: “I have opened up every path which is in the sky and on earth, for I am the well-beloved son of my father Osiris. I am noble, I am a spirit, I am equipped; O all you gods and all you spirits, prepare a path for me.”

Resources

- ARCE. “Book of the Dead: A Guidebook to the Afterlife.” Accessed August 21, 2023. https://arce.org/resource/book-dead-guidebook-afterlife/.

- Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt / ILL TN 2182983, n.d.

- Buck, Adriaan de, Alan H. Gardiner, and James P. Allen. “The Egyptian Coffin Texts.” The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications ; v. 34, 49, 64, 67, 73, 81, 87, 132. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1935.

- Ikram, Salima. “The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity.” New York: Thames & Hudson, 1998.

- “In Our Time - The Egyptian Book of the Dead - BBC Sounds.” Accessed May 19, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b08n1y2v.

- @NatGeoUK. “The Book of the Dead Was Egyptians’ Inside Guide To The Underworld.” National Geographic, February 10, 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history/2019/02/the-book-of-the-dead-was-egyptians-inside-guide-to-the-underworld.

- O’Rourke, Paul F. An Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Papyrus of Sobekmose. London] : New York, NY, United States: Thames & Hudson, 2016.

- Ouellette, Jennifer. “Archaeologists Discovered a New Papyrus of Egyptian Book of the Dead.” Ars Technica, January 21, 2023. https://arstechnica.com/science/2023/01/archaeologists-discovered-a-new-papyrus-of-egyptian-book-of-the-dead/.

- Taylor, John H. Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: Journey through the Afterlife. London: British Museum, 2010.

- The British Museum. “What Is a Book of the Dead?” Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/what-book-dead.

- TlMES, Special Correspondence Thb New York. “Part of a Splendid Copy on Papyrus of the ‘Book of the Dead.’” The New York Times, December 11, 1910.

- “UAX #44: Unicode Character Database.” Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/.

- “What Is the Egyptian Book of the Dead?” Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.getty.edu/news/what-is-the-egyptian-book-of-the-dead/.