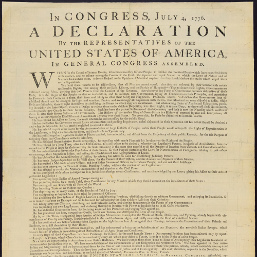

Declaration of Independence deleted passage, 1776

How do you read something that isn’t there? Well, you can’t, unless somehow you know it used to be there. There are lots of examples the creative process at work in all its messy, myriad varieties - multiple drafts of novels, plays, poems, symphonies and so on, showing us how works are tweaked and pruned and sometimes taken apart and put back together again.

Transcript

How do you read something that isn’t there? Well, you can’t, unless somehow you know it used to be there. There are lots of examples the creative process at work in all its messy, myriad varieties - multiple drafts of novels, plays, poems, symphonies and so on, showing us how works are tweaked and pruned and sometimes taken apart and put back together again.

This is often true, particularly, in lawmaking; in a contemporary legislature, meticulous minutes are kept recording proposed amendments, speeches made, votes taken and so on, so that the public, and future generations, can know, if they care, how it all happened and moreover who to thank or blame if their particular provision made it, or didn’t.

This wasn’t always the case, and one of our most cherished and fundamental documents underwent a serious of edits and revisions from the trivial to the profound, and we are largely in the dark as to how and why, and one piece in particular, taken out in one of the most pivotal decisions in our early history, resounds, even – especially - in its absence, today.

A document that changed the world: A passage, beginning with “He has waged cruel war,” deleted by the Second Continental Congress from the Declaration of Independence, 1776.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School, and that date is so ingrained in the American consciousness that it sort of blots out everything else going on that year. The first volume of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was published, as was the Wealth of Nations, Catherine the Great is in the middle of her reign, Louis XVI in the third year of his, and the Phi Beta Kappa society is founded at William and Mary that winter. But pride of place goes to the document drafted by Thomas Jefferson in a second-floor rented apartment on the corner of 7th and Market Streets in Philadelphia on behalf of a committee of five members of Congress.

There are many, many stories about the Declaration, including the early printed copy I nearly sneezed on one winter’s morning at the Library of Congress, but those will have to wait for another day. The basics: Jefferson was much more interested in helping to prepare Virginia’s new constitution and only somewhat reluctantly took on the task of drafting it; John Adams later claimed he talked him into it. He borrowed freely from numerous sources, and his initial effort went first to the rest of the committee, including Adams and Benjamin Franklin, who then made some 47 changes, mostly minor, adding several paragraphs.

There are 7 versions and fragments in Jefferson’s hand, including what’s known as the “original Rough Draft” which looks like exactly that. It’s got crossouts, additions, boxes, even a pasted-on flap, showing how the text evolved, if not the reasons or people responsible. For example, somehow we got from “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” to “self-evident.” Who did that? Franklin, Adams, Jefferson? We don’t know. To this day, research goes on about the writing and editing processes, including recent sophisticated imaging studies of Jefferson’s drafts.

Congress debated the committee’s submission over three days before adopting it on July 4. The original resolution on declaring independence was passed on the 2nd, but nobody remembers that. We celebrate the adoption of the Declaration on the 4th as our national holiday rather than, say, the adoption of the Constitution or even, as John Adams predicted, the 2nd, when the decision was actually made. Congress made a further 39 edits, which seriously annoyed Jefferson who by now was feeling more than a little protective of the prose, later calling his colleagues “pusillanimous” in trying not to offend the British people too grievously.

Anyway, adopted it was, and the committee took it to their official printer, John Dunlap, that night to have printed copies made. 26 of these “Dunlap broadsides” are known to survive; one discovered hidden in a picture frame at a flea market in 1991 fetched $2.5 million dollars at auction. The engrossed version, handwritten, was signed, first by John Hancock, beginning on August 2. That has had a journey of its own, being moved at least 20 times, including sitting in the sun for about 35 years in the Patent Office, in a State Department library room with an open fireplace for another 17, and a trip to Fort Knox to wait out World War II. It has resided since 1952 in the National Archives, now in the rotunda, protected by a monitoring system designed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and not at all susceptible to being stolen and rolled up like wallpaper like you saw in National Treasure which I can’t believe they sell the DVD of in the Archives’ gift shop. Seriously.

The Declaration has been inspirational, not only for its words and ideas, but as an idea unto itself. Visit the Alamo in San Antonio, and you’re treated to considerable discussions about the Declaration of Independence – of Texas – signed in 1836. South Carolina’s 1860 declaration of secession explicitly references it as well. In 1777, only a few months on, a “Petition for Freedom” from “A Great Number of Blackes” was submitted to the Massachusetts legislature. Declarations of independence have been composed over the decades by labor groups, farmers, women, socialists, and others. Frederick Douglass asked, in an 1852 speech, “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?”

One of the most serious amendments removed a section of some 168 words, laying out one of the litany of charges and accusations against George III, piling up the indictments and thus justifying the quite novel idea of breaking away. It is typically known by its opening words as the “He has waged cruel war” passage, and it accuses the king of perpetuating the slave trade and by inference slavery itself. Adams said in 1822 he never thought it would get through, though his otherwise comprehensive diaries of the relevant days are silent on what happened. Jefferson also was sanguine if a bit snippy about it, saying it was “struck out in complaisance to South Carolina & Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves…Our Northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender … for tho’ their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.”

The congressional journal is of no help on what actually happened; it simply records that there was discussion and debate, as a committee of the whole, and approval, but that’s it. The next order of business concerned the hiring of a boat from a Mr. Walker.

Much has been written about Jefferson’s deeply conflicted position as slaveholder and as defender of individual rights. At the time of the Declaration’s drafting, he owned 180 slaves, rising to 267 by 1822. He had 6 children by Sally Hemmings, his slave and dead wife’s half-sister, and he did not, as was often the practice, free his slaves upon his death. There are few clean hands here; at least a third of the signers were slaveowners, and even in northern states abolition was gradual; New York didn’t outlaw slavery until 1827, the 1840 census lists seven slaves in Rhode Island, and in at least a few Union states full abolition wasn’t achieved until 1865. And lest we get too smug about all this, estimates put the current number of people in forced labor or human trafficking today at between 20 and 35 million.

This edit can be seen as ordinary and unremarkable; this sort of thing happens all the time: provisions are drafted, revised, taken out, added, re-revised, and so on, all part of the process of discussion and coming to agreement.

For many, though, this is the American national mark of Cain; the proverbial can that has been kicked down our proverbial road for nearly a quarter of a millennium. Yes, it’s true, as well as cliché, to say that progress has been made – including the Fourteenth and Nineteenth Amendments (to a Constitution that countenances slavery without ever soiling its hands by using the word outright). You could also point to civil rights legislation, Supreme Court decisions from Brown to Obergefell, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and so on. And yet, well, you know.

Any writer will tell you that less can be more, and many is the time I was losing the battle with something I was writing, and discovered that using fewer words could cover more territory and solve my problem. By the same token, though, sometimes more is more, more words, more ideas, more voices, more people. Alloys are stronger for a reason.

This decision has been second-guessed, criticized and defended since, it seems, day one; many believe the Declaration and the new nation would never have worked otherwise. Quite possibly – though that doesn’t remove the inherent sting. It’s hard not to think of this as a missed turning, an opportunity lost.

So, we finish where we started: how do you read something that isn’t there? There’s a difference between something that just isn’t there and never was, and something that’s been removed, intentionally, purposefully. Perhaps knowing how that happened and why and by whom would be useful, or make a difference, perhaps not; without a more comprehensive record, we shall never know. Ultimately, this is a story about grand and noble language and ideas, which have stirred souls for generations, and, within, a silence, which nonetheless speaks volumes, still.