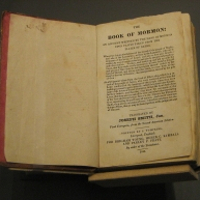

Book of Mormon, 1830

Joseph Smith: finder of long-buried golden tablets revealing lost truths or the most successful humbug ever known?

Transcript

You know those things you hear about when you’re so young you just take them for granted, without thinking too hard about them? For me, growing up near the center of New York State, one of those things was the Hill Cumorah Pageant. I can remember commercials coming on every summer advertising this, and while I had no idea what it really was, I thought it looked pretty darned impressive—lots of lights and dramatic music, a cast of hundreds in historic looking costumes—all acted out on a hillside maybe a couple of hours’ drive away. I don’t actually remember wanting to go see it, and I doubt my parents would have agreed, but I do remember thinking I might have been missing out on something.

Little did the preadolescent me suspect that all the fuss was centered on a book, first published near that hill nearly 150 years earlier, with a mind-stretching backstory, that begat a movement which started out and remains controversial, and that’s still growing and spreading all over the planet.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. Here’s the deal. Joseph Smith, Jr., aged 17, is visited by an angel in white, Moroni, who tells him there are golden plates buried not far away revealing a forgotten history of people who traveled to the Americas centuries before, their religious struggles and conflicts, and their visitation by Jesus just after his crucifixion and resurrection. Four years later, Joseph is allowed to take the plates along with devices that will allow him to translate them from their original characters he called “Reformed Egyptian.” A series of hiding places, translation venues, helpers, and misfortunes ensue, including threats from local mobs and the theft of the first 100 pages or so by an associate’s wife—all done in secret. He dictates translations from behind curtains or with the plates wrapped in linen, often with a “seer stone” in his hat to help out, sometimes without even looking at the plates. It’s an itinerant, on-again-off-again process, until a burst of activity over 3 months in 1829, when at the rate of 3500 words a day the work is largely completed, yielding a work of about 600 printed pages. This doesn’t include a series of plates that he’s told must remained sealed until humanity is worthy. Joseph allows nobody to see the plates for years, not even his long-suffering wife, until he reveals them to a series of witnesses who later swear to their existence. Drawings of the plates resemble a very thick three-ring binder, holding together many hundreds of thin metallic sheets. When he’s finished, Moroni then takes the plates back. “Mormon,” Moroni’s father, is one of the series of chroniclers who wrote the several books now collected and known as the Book of Mormon.

The first print edition, underwritten by a wealthy local farmer who mortgaged his farm, appears quickly, in 1830, and sells poorly, at $1.25 a copy, in no small part because of its length, complexity and awkwardly simple wording (it uses only about 2200 words); Mark Twain later refers to it as “chloroform in print.” Slowly it gains traction, though; a second edition incorporating numerous revisions based on new revelations by Smith appears in 1837, followed by a British edition in 1841, and the first translation, into Danish, ten years later. By 1900, it’s available in 10 languages including Maori and Hawaiian, by 1950, 10 more, by 1980 a total of 40, and now well over 100 languages; it can be read by 90% of the world in their native language, and over 150 million copies have been printed.

The text is very precious to the Latter-Day Saints church that Joseph Smith chartered even before the book was published; any changes in wording must be approved by senior church leadership. The vast majority of copies are produced in one plant, on one press to ensure quality and authenticity, the text is copyrighted and the name trademarked. It’s been filmed a couple of times, in a 1915 silent version now lost, then an elaborate production in 2003 that flopped badly; the Hill Cumorah Pageant, with a mid-1980s script by science-fiction author Orson Scott Card is by far the best and best known representation, not counting the musical, um, homage, that won 9 Tony Awards in 2011. I was impressed, if not surprised, that the church bought several slick full-page ads in the program of the version I saw—betraying I think less a sense of humor about themselves than shrewd marketing: if you liked the musical, read the book that started it all!

The original manuscript had little punctuation and no chapter and verse markers, which have since been added—as with the Old and New Testaments, those devices, like so many in printed books, are meant to make it easier to read and refer to. The actual manuscript was sealed up in a cornerstone for 40 years where it badly degraded. Only about a quarter of the pages are known to survive, much now held by the LDS church archives, while the printer’s original manuscript is owned by the Community of Christ, one of a number of rival denominations founded in the mid- 19th century.

Its early appeal was partly due to the quite intriguing notion that heaven was open again, that God continues to speak, that lost truths were being revealed in what was a time of place of great religious commotion.

OK, OK, I can hear you saying—this is all fine and good, but is the thing legit? Is it on the level, or just the ravings of a religiously-crazed dirt farmer from upstate New York? Let’s say this— nobody likes the authenticity of their founding religious text called into question, let alone held up for public ridicule in, say, a big splashy hit Broadway musical including a number called “Making Things Up Again”. There’s reams of scholarship and speculation on both sides, including theories of plagiarism, people who have scoured to find places mentioned in the book and for the kinds of plants and animals and tools specified (like steel being used several centuries before it was developed) and finding nothing of the sort, and who find the whole origin story patently ridiculous, not to mention the original version gave Jesus’ birthplace as Jerusalem rather than Bethlehem.

LDS scholars have developed ways around these objections, including the “limited-geography theory,” which comes across like sticking your fingers in your ears and going la la la. They also raise the quite valid point that it seems highly unlikely that a lightly educated 24 year old could make something this complex and narratively unified up on his own. If you’re a believer, any evidence to the contrary hasn’t swayed you; if you aren’t, you’ve already made up your mind, and if you haven’t, go read it and decide for yourself.

With this, as with any religious text, or lots of other kinds of text for that matter, the question is: where did the words come from? Here we know, sort of. Joseph Smith dictated words that got written down and it seems pretty certain what we have is what he said. So then the question is where he got them from; for every objection that the whole story is ludicrous on its face, and those are myriad, there’s the counterpoint: how would he have been able to pull this off? Whatever its actual genesis is, there’s one thing that’s certain: it comes from one source and one time, so its unity and intactness guarantee there’s no partial credit. It either is what it purports to be, or it’s not. Brigham Young’s son once said “if it is a humbug, it is the most successful humbug ever known.”

And thus we get to faith. For which no amount of textual analysis, archaeology, or forensic psychiatry gives us answers. Words are so often the seeds of faith, and these words have taken root and flowered; the LDS church claims 15 million members worldwide, 6 million in the US, about as many as Judaism and more than Presbyterianism. The signature number in the musical is a beautifully heartfelt—and scathingly funny—song called simply, “I Believe,” and ultimately that’s what this story is all about—belief, and the words that lead you there, no matter what anybody else thinks.

Gutjahr, P. C. (2012). The Book of Mormon: a biography. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Hardy, G. (2003). The Book of Mormon a reader’s edition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Larson, S. (1996). Quest for the gold plates: Thomas Stuart Ferguson’s archaeological search

for the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City: Freethinker Press in association with Smith

Research Associates. Morain, W. D. (1998). The sword of Laban: Joseph Smith, Jr. and the dissociated mind.

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.