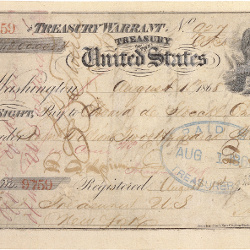

Alaska Purchase Check, 1868

It’s strange that while a check can’t purchase gas for your car, it did purchase one of the biggest oil fields in the world, an area that turned out to be more than America’s last frontier.

Transcript

Have you ever seen someone try to pay for a purchase over $5 with just coins? Or what about using a $100 bill to purchase a candy bar? And wouldn’t it be unusual to purchase a big- scale item like a computer without a credit card? It seems as if different circumstances require different forms of payment. Throughout history, money could be anything from seashells to green slips of paper with the head of a United States president on the front.

I know when I graduated high school last year, I received money from friends and family. While the Alexander Hamilton’s and the Andrew Jackson’s were always great to see, it seemed as if the big bucks actually wasn’t in bills, but in the form of a check. Receiving cash meant I could just stuff it into my wallet, and do whatever I wanted with it. However, with a check, the options were far less. It’s strange to me that a check can’t purchase gas for your car, but did purchase one of the biggest oil fields in the world, an area of the world that turned about to be more than America’s last frontier, and also a region of the country that has surprisingly shaped our nation’s history more than what you would have expected.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School, and I’m joined by my student Andrew Kyrios, who researched, produced and co-wrote this episode It’s widely believed the Russians were the first Europeans to reach Alaska, and by 1773 the land was known as Russian America. Colonies began sprouting as fur traders came to the area, dreaming to get rich off the abundance of fur. They forced many Aleut people into slavery, ordering them to hunt sea otters to the brink of extinction. Along with the traders, Russian missionaries also migrated to the area to convert the Natives, specifically the Athabascan, Yup’ik, Koniag, Tlingit, and Aleuts to the Russian-Orthodox faith and taught them to read and write in Russian. As the colony progressed, New Archangel (current-day Sitka) was named the capital, and fur tycoon Alexander Andreyevich Baranov was named to govern the settlement.

However, by the 1860’s, the Russian government no longer valued their American colony. The fur-bearing animals were all but gone, and protecting and supplying the area became a burden. Even worse was the possibility of the British taking over the land for nothing. Financially troubled after the Crimean War, Alexander II, Emperor of all the Russias offered to sell the land to either Britain or America, and hoped to start a bidding war. Britain, however, wasn’t interested and the United States was a bit distracted by the Civil War.

Negotiation reemerged after the war. The Russians believed if America purchased Alaska, Britain’s colony of British Columbia would be surrounded and thus greatly weakened. This was a time of considerable upheaval, amid American westward expansion and the period of Manifest Destiny—the Transcontinental Railroad was completed just a year later—the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, as well as Reconstruction. Nevertheless, on March 30th, 1867, Secretary of State William H. Seward negotiated the purchase of Russian America for a price of 7.2 million dollars. America just increased her size by almost a quarter, nearly 600,000 square miles, for a mere 2 cents per acre.

The Treasury Warrant, issued on August 1, 1868 at the Sub-Treasury Building at 26 Wall Street, was made out to Edouard de Stoeckl, a Russian diplomat (whose father happened to be an Austrian diplomat) who acted as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the Russians. The check was signed by Treasurer of the United States Francis E. Skinner (who, as signer of currency, liked to claim he had the most familiar autograph in the country). The Treasury check was cashed, with de Stoeckl’s endorsement on the back, at Riggs Bank in Washington D.C., and his handwritten receipt verifies he got the specified amount “in coin”. The warrant itself looks like...a check, albeit a schmancy one, quite impressively featuring engraved figures, flowery 19th century handwriting filling in the standard information, Skinner’s distinctive signature, and a large blue stamp saying “PAID” with the date.

Some Americans were not pleased with the acquisition. Known by the media as Seward’s Folly, the public believed it was a foolish purchase. Although he faced criticism, when asked what his greatest achievement was as Secretary of State, his response was “the purchase of Alaska—but it will take the people a generation to find it out". de Stoeckl didn’t receive much love either. He was accused of taking bribes and decided to quit his job as a diplomat and moved to Paris with his American wife, who he had happened to meet while negotiating the deal in the States.

So was it really worth it to buy Alaska? The name calling ended in the 1880’s when gold was first discovered, and the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896 attracted 100,000 people to the area, followed by the Nome Gold Rush. In leading up to World War II, U.S. General Billy Mitchell stated “I believe that in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world. I think it is the most important strategic place in the world.” The Aleutian Islands Campaign, often referred to as the forgotten battle of World War II, played a key part in the war between the Japanese and the Americans. The Lend-Lease program, which we’re used to thinking of only concerning Great Britain, also involved flying airplanes to Alaska, and then allowing the Soviets to use them in their fight against Germany. Alaska was admitted as the 49th state on January 3rd, 1959.

Check systems seem to have been common in the eastern Mediterranean and Muslim world by the 10th century and made their way to Europe, in fits and starts, by way of Crusaders and their, ahem, experience with the monetary systems they encountered along the way. Because paper could be forged, early European banks made payments and transfers by oral order, meaning that everybody had to meet up and agree who was paying who how much. Forms such as “bills of exchange,” which instructed someone in another city to make a payment after a certain period of time, gave rise to something closer to what we know today as a check by the 15th century or so, as their convenience, versatility and acceptance increasingly outweighed the risk of fraud, abuse, and distrust of banks.

The use of checks began to grow steadily in the mid-19th century into the 20th century and peaked during the early 1990’s with a total of 50 billion checks written and collected per year.

Since then, the uses of checks have sharply declined. Some say the death of the paper check was triggered by 9/11. Many checks were destroyed that day, and the grounding of the air fleet for several days also held up the delivery of many more. Congress then passed the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act which permitted banks to use electronic copies of checks instead. Banks were and still are fine with this because checks cost more to process so they’re saving a pretty penny every year. The United States government is also doing away with checks. Starting in March 2012, federal benefits from Social Security and Veteran’s Affairs are no longer distributed in the form of a check, but through direct deposit or debit cards, which the government estimates will save $120 million a year.

With more payment options today, many people prefer to use credit or debit cards, along with electronic and online payments such as Paypal. However, some people, especially older folks like me, are reluctant to see checks go. Some of us appreciate the actual object, and believe it is safer or more reliable than purely electronic methods. In 2011, the United Kingdom banking industry actually planned to eliminate checks by 2018, but that idea went nowhere after complaints from senior citizens, small businesses, and charities.

Cutting money to save money seems to be the name of the game. Along with the decline of checks, critics have also demanded for an end to the penny. It costs 2.4 cents to manufacture one penny, which honestly seems a little counterproductive. Canada is phasing theirs out, and President Obama even said he is willing to eliminate it. The way money is spent is definitely evolving. It will be interesting to see if the old-fashioned way of spending will be completely taken over by the digital world of electronic money. But for now once a year, I can always expect a check from my grandmother; and written in the memo says “Happy Birthday”.