Airplane Black Box/Flight Data Recorder, 1958

A black box that reveals, not conceals. How flight data recorders were developed, how they work, and what happens to the information inside them.

Transcript

Did you know there’s a name for words that have two contradictory meanings? There are several, in fact, for words like “cleave,” to separate or cling together, “oversight,” to look for a mistake or miss one, or “sanction”, to condone or to punish. These are sometimes called auto-antonyms or self-antonyms, contranyms, or my favorite, antagonyms. These must be a nightmare for learners of English, think about the two meanings of “inflammable,” which can either mean something that won’t burn, or something that will, which is about as contranymy as you can get.

Now imagine a document, itself intended to be inflammable, that embodies contradictions of many types: an aftereffect of tragedy meant to help understand and to prevent further ones, and something you very much want to be there, constantly doing its job, and which nobody ever wants to be needed or read.

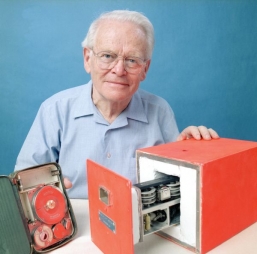

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. There’s no clear, single inventor of the flight data recorder, several simultaneous and separate streams of work were going on as far back as the late ‘30s in France, continuing throughout World War II, including the “Mata Hari” used in test flights in Finland in 1942. Charles Lindbergh used a device to track and record altitude on a rotating spool for his transatlantic flight. Many sources, however, point to the seminal work of David Warren, a chemist working on fuel combustion, who, while sitting in a meeting discussing potential explanations for the crash of an early jet called the Comet, let his mind wander toward an early wire recorder he’d seen and thinking how valuable that might be as a means for logging sounds and voices in cockpits. There follows a long and onerous odyssey over five years, beset with indifference and bureaucracy, strongly flavored with gumption and stick-to-it-iveness, which yielded a prototype system in 1958 incorporating many elements now familiar: ways of recording both voices and data about the flight in a housing meant to survive the extreme circumstances of an airplane crash and explosion.

There’s also no one explanation for why flight recorders are often called black boxes, perhaps because early ones needed to be black to prevent exposure of photographic film used inside as a recording medium, or perhaps because when recovered they were so often charred and burned black. In any event, they’re now bright orange, and labeled FLIGHT RECORDER DO NOT OPEN in English and French.

Most people hear, and think, about flight recorders only after a crash, and they’re usually put in the back of the plane since, as somebody once said, planes rarely back into mountains. The data can, though, also be downloaded for ongoing monitoring purposes, to check on fuel usage, for example. Not long after Warren’s prototype was constructed, a 1960 crash inquiry led to Australia being the first country to mandate their use, in 1963; the US followed a year later. They’re now commonplace also in cars, ships, and trains.

Flight recorders today use solid-state memory, replacing prior systems that used magnetic tape, able to store 2 hours of audio data (the last 2 hours, constantly overwriting) and 25 hours of flight data. US federal regulations require 88 parameters to be recorded, though the Boeing 787 can record nearly 150,000, requiring sophisticated analysis software. Time, altitude, airspeed, acceleration, heading, positions of controls, fuel flow, and more are constantly being recorded in a device that is tested to survive 3,400 Gs, 5,000 pounds per square inch of pressure, 2,000 degrees F for an hour, submersion in salt water for 30 days and having a 500 pound weight with a 1⁄4” spike dropped on it from 10 feet. If it makes contact with water, an underwater locator beacon is activated, inaudible to humans, pulsing at 37.5 KHz once a second for about a month until it loses power. Data is retrieved via means familiar to many of us: a USB or Ethernet port.

No matter how durable they’re designed to be, they don’t always survive and they’re not always found. A number of recorders are still unrecovered, going as far back as a United Airlines plane that crashed in Lake Michigan in 250 feet of water in 1965. Others are presumably 20,000 feet up an Andean mountain, in the Persian Gulf or the Andaman Sea or 16,000 feet deep in the Indian Ocean—from a 1987 South

African Airways crash near Mauritius. Only one survived from any of the hijacked planes on 9/11: the cockpit voice recorder from United flight 93, which crashed in Pennsylvania.

When they are found, the National Transportation Safety Board has a highly structured 12-page protocol for their recovery, encompassing many procedures and safeguards about their custody, authority, preservation and in particular flow of information about the data itself and its interpretation—to whom, how, and when, in minute, even picayune detail, perhaps betraying an overly sensitive and bureaucratic mindset or the product of unfortunate experience. One learns here to pack it in bubble wrap and seal it inside a plastic beverage container, if it’s in water, keep it in water, and ship it via commercial airliner. Data briefings must be done over landlines and not cell phones, premature release of information is grounds for disciplinary action, and foreign investigations with NTSB help are exempt from Freedom of Information Act requests for 2 years.

As a documentary form, flight recorders bear strong similarities to a couple of familiar parallels: the ship’s log, historically meant to record the distance and time traveled and other important milestones of a maritime journey, and, weirdly, the 8 track of the 1960’s and 70s which was also a single eternal loop of magnetic tape which could play, say, Jethro Tull’s album Aqualung over and over, incessantly, until your roommate finally turned it off. But I digress.

The whole black box idea betrays a static mindset: plane takes off, things happen, they get recorded, and if something really bad happens, find box and examine data. Today, that’s not the only way it could go; much if not all of this data could be streamed and collected in real time; one computer scientist has proposed metaphorical “glass boxes” to highlight the transparency, ubiquity and invulnerability they would provide. Opposition to this idea has come from a source that has dogged the flight recording process from the get-go, namely pilots. The Australian pilot’s union was cautious about the very first systems, fearing Big Brother-like surveillance of their actions; similar objections have been raised about introducing cockpit cameras.

Warren and his colleagues named their invention the “Flight Memory,” and though generally credited with most of the important ideas and innovations we now know, they were never able to patent them or realize much monetary benefit from them. An English-made device based on their design survived a 1965 crash in London, which must have been vindication of a sort. Warren went back to his laboratory until his retirement in 1985; when he died in 2010, somebody thoughtfully attached a label to his coffin: FLIGHT DATA RECORDER INVENTOR: DO NOT OPEN.

Let me point out one final contradiction here—and that’s the name “black box.” Another contranym. There are other uses of that phrase, for a plain, blank theater space, for a serious warning on a pharmaceutical label, a nickname for the President’s “nuclear football” and even a mutant in the Marvel comics universe who can telepathically extract information from any electronic device. Often, however, a “black box” is something opaque, impenetrable, a process or system of unknown operation that just works, sort of in the ‘don’t ask any questions and nobody gets hurt’ kind of way. Here it’s just the opposite, a device nobody wants to be opened, but when it is, it’s meant to reveal, to provide answers; the vast majority never really used for their full purpose, but when one does, everybody knows.

References:

Beyond the Black Box - IEEE Spectrum. (n.d.). Retrieved April 23, 2014, from http://spectrum.ieee.org/aerospace/aviation/beyond-the-black-box Browsing by theme “ARL Flight Memory Recorder” - Museum Victoria. (n.d.). Retrieved April 23, 2014,

from http://museumvictoria.com.au/collections/themes/3720/arl-flight-memory-recorder David Warren (inventor). (2014, April 21). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=David_Warren_(inventor)&oldid=604833514 Flight recorder. (2014, April 23). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Flight_recorder&oldid=604984665 Flight recorder (recording instrument). (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved April 23, 2014, from

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/210220/flight-recorder HowStuffWorks “How Black Boxes Work.” (n.d.). HowStuffWorks. Retrieved April 23, 2014, from

http://science.howstuffworks.com/transport/flight/modern/black-box.htm List of unrecovered flight recorders. (2014, April 15). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_unrecovered_flight_recorders&oldid=603527998 National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (2004). The 9/11 Commission report:

final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (T. H. Kean & L. Hamilton, Eds.) (Official government ed.). Washington, DC: National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States : For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O.

National Transportation Safety Board Vehicle Recorder Division. (2002). Flight Data Recorder Handbook for Aviation Accident Investigations. Retrieved from http://www.ntsb.gov/doclib/manuals/FDR_Handbook.pdf

Sear, J. (2001). The ARL “Black Box” Flight Recorder--Invention and Memory (Master’s Thesis). Department of History, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved from kenblackbox.com/other/The_ARL_Black_Box_Flight_Recorder.pdf