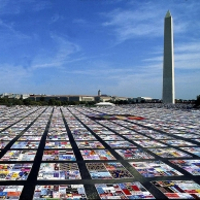

AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1987

Is a quilt a document? The AIDS quilt, which comprises more than 48k panes representing more then 94k names, certainly documents the many stories associated with the AIDS epidemic.

Transcript

Remember when it was fun to be sick? As an adult, it’s a lot less enjoyable, but as a kid, you could stay home from school, get spoiled, have grilled cheese sandwiches and tomato soup, and be wrapped up all warm and cozy; maybe if you were lucky you might even get a story read to you.

Stories are important—that’s why there are so many kinds and so many ways of telling them, including through documents. Some do this in a straightforward way, like the Declaration of Independence. Others tell us more about their creators and their rationales, their subjects and contexts, incidentally. Consider the wanted poster for John Wilkes Booth, intended at the time to help track down the most notorious fugitive in the nation’s history, and coincidentally one of the first wanted posters to feature a photographic image, his theatrical publicity photo. Today you could argue that that poster tells a long and unpleasant story drawing a straight link back the Declaration and its shortcomings.

Documents come in lots of shapes and sizes and forms. Reports, charts, maps, statistics, they all have their purposes and intents, could all be useful individually or together to describe, for example, the adoption of a new teaching method or the spread of a new virus.

What about a quilt? Can a quilt be a document? Sure it can—they can record and tell the stories of individuals, families, communities, events, and histories. By its very nature, they’re an assembly of various materials, and it’s a very old form; the earliest known patchwork textiles go back at least 5000 years and its use as a metaphor at least 400.

One quilt, the largest of its kind—in fact so large it will likely never again be intact—has documented its subject in a way so vivid, so undeniable, so real, it helped to change the way many people perceived an unknown and frightening disease.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. It isn’t entirely clear when HIV first made its way to humans; there is some evidence it could have been as early as the late 19th century, though documented individual cases of deaths seem to appear around 1959. Public attention wasn’t focused until larger numbers of cases occurred in urban areas, and the name “AIDS” wasn’t officially put into use by the CDC until 1982.

Once it hit the popular consciousness, though, it cut a huge swath, particularly since so little was known about it and because the earliest largest concentrations of cases were found in specific, often marginalized populations: Haitian immigrants, hemophiliacs, intravenous drug users and gay men. At a candlelight vigil in San Francisco in 1985, already the site of hundreds of deaths, names of victims were carried on placards and then assembled on a wall, bringing to mind a patchwork quilt. And thus, in a moment, the idea was born. Cleve Jones, the march organizer, made the first panel for his friend Marvin Feldman in 1986, and the idea spread rapidly. An organization was formed and by October of 1987, nearly 2000 panels were displayed on the National Mall in Washington, where it was viewed by half a million people.

The quilt continues to grow, now comprising over 48,000 panels representing more than 94,000 names. Each panel is 3 by 6 feet, roughly the size of a grave; if assembled it would cover 1.3 million square feet and weigh 54 tons. In 1989, the project was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, the same year a film about it won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. You know you’ve arrived when Miss America accompanies you down Pennsylvania Avenue in a presidential inaugural parade, for Bill Clinton’s first inaugural in 1993.

As new panels are submitted, they are now photographed and a database of those along with additional materials such as letters, photographs, and biographies is also maintained. This leads to the inevitable challenge of description and organization; each panel receives a unique code number, but given the multiple varieties of interest (art historians, quilters, researchers, students, not to mention people just looking for a name), there will have to be considerable attention paid to appropriate metadata to facilitate search. There’s also a significant need for conservation efforts; as panels are moved and displayed, they’re exposed to light, heat, moisture, dirt, bugs and who knows what else, not to mention being handled, and the materials themselves have special needs.

Consider how you might keep all of the follow safe and intact: every kind of fabric and textile you can imagine, from lace to mink to suede to bubble wrap and metal, gems, clothing, hair, wedding rings, cremation ashes, jockstraps, condoms, bowling balls, and the inevitable feathers and sequins.

The goals of the project include remembrance, awareness, education, and fundraising, most of which are inherently difficult to assess, though its scale and reach are clear. It has inspired other similar memorials, for those killed in action in Iraq, victims of the 9/11 attacks, other diseases, even virtual memorial quilts. It’s inevitably political—it started in a time of growing and evolving activism, often confrontational in nature, and people in some quarters criticized the quilt project as not provocative enough.

The quilt has several examples of intriguing features as a document. It may never be finished, and if it was, how and when would we know? It also has no single, inherent structure or order; the blocks of panels could be connected in an infinite number of ways, each equally effective and authentic. As it almost certainly will never be fully assembled again, it exists only, exclusively in fragmentary, federated form—a collective enterprise not only in construction and maintenance but also in configuration. You might even say it now functions more as a collection than a single item—never intact, but bounded and defined and distributed, increasing the possibility for impact.

Perhaps, though, the most satisfying and genuine explanation of its power is the simplest. It’s a quilt. The individual panels are objects of love, loss, pain, remembrance and hope, and like any quilt, it’s a symbol of comfort and warmth and home—for those who have gone and for those who remain.

References

Biggs, John. The AIDS Quilt, Digitized: Microsoft And The NAMES Project Team Up To Bring Remembrance Project Into The 21st Century | TechCrunch.

http://techcrunch.com/2012/07/24/the-aids-quilt-digitized-microsoft-and-the-names-project- team-up-to-bring-remembrance-project-into-the-21st-century/

Capozzola, Christopher. (2003). AIDS Memorial Quilt--Names Project. Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History in America. Scribner’s.

Global HIV/AIDS Timeline - Kaiser Family Foundation.

http://www.kff.org/hivaids/timeline/hivtimeline.cfm

Kulpa, Robert. (2010). Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. LGBTQ America Today. Greenwood Press.

NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NAMES_Project_AIDS_Memorial_Quilt

Rosen, Rebecca. A Map of Loss: The AIDS Quilt Goes Online - Rebecca J. Rosen - The Atlantic, from http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/07/a-map-of-loss-the-aids-quilt-goes- online/260188/

The Names Project — AIDS Memorial Quilt. http://www.aidsquilt.org/