18 1/2 Minute Gap, 1972

For a time, a great deal of attention focused on one strip of magnetic tape, about 90 feet worth, with an unexplained buzz where there should have been conversation between two of the most powerful men in the country.

Transcript

Don’t we all love a good mystery? At the end of a Miss Marple novel or an episode of CSI:, all is revealed, the guilty are exposed and justice and harmony reign. Unsolved mysteries, though, are a good deal less fulfilling; untied loose ends are really not appreciated. That’s why people continue to puzzle over what happened to Amelia Earhart, who Jack the Ripper really was, and why Ryan Seacrest is so popular.

To people of a certain age, one mystery, now a bit forgotten in the mists of time, brings back floods of memories, reminding us of once-novel and colorful phrases like “expletive deleted,” “dirty tricks,” and “unindicted co-conspirator”. If you’re too young to remember the Saturday Night Massacre or the smoking gun, you missed one of the most turbulent times in the nation’s history, when the resilience of the constitution was seriously in question, and the question of the time was “What did the president know, and when did he know it?” which, sadly, we’ve heard a few more times since then.

For a time, a great deal of attention focused on one strip of magnetic tape, about 90 feet worth, with an unexplained buzz where there should have been conversation between two of the most powerful men in the country. Its mere existence contributed to the growing sense of cynicism and further undermined people’s trust of the government and other institutions. The mysteries locked up in that tape and what is and isn’t there transfixed the nation at the time, and still do for some, and the desire to know, to figure it out, goes on.

I’m Joe Janes, of the University of Washington Information School. Let me give away the ending here—we don’t know what’s in the 181⁄2 minute gap, though not for lack of trying to find out. The conversation in question was of Nixon and Haldeman’s meeting on June 20, 1972, starting at 11:30 am. June 20 is 3 days after the Watergate break-in on the 17th, and, entertainingly, one day after a unanimous Supreme Court ruled that the government had no authority to spy on private citizens without warrants. Ah, those were the days. It’s also, sadly, the day Howard Johnson went to that big HoJo’s in the sky.

Nixon wasn’t the first president with a penchant for recording; FDR, JFK, and LBJ indulged as well, though not with nearly such thoroughness. Microphones were also installed in the Oval Office and Cabinet Room and Camp David, including phone lines. In total, about 3500 hours of recordings were made, now housed in the National Archives and the Nixon Presidential Library, after a string of legal battles lasting 25 years over disputes on executive privilege and national security.

The recording itself is hard to understand; the voices are faint, there’s an odd burping noise from the voice-activated recorder starting and stopping and mostly, it’s deadly, deadly dull. Imagine sitting in on somebody else’s meeting, that you have no involvement in, and bring a pillow. They talk about the weather, the president’s schedule, magazine coverage, a woman running for congress from Michigan, and the recent flooding in Rapid City, South Dakota. In the middle of discussing sending Mrs. Nixon to visit (she went), the voices stop abruptly, 7:12 into the tape, and a penetrating and persistent buzz begins. This lasts for the now-infamous 18 1⁄2 minutes, before stopping as abruptly, when they’re discussing the upcoming Democratic convention, before turning to weightier matters like Haldeman’s opinion of the movie Hot Rock.

That's it. Recording went on for another year or so, until the existence of the tapes, a closely held secret, was revealed as part of the Watergate hearings.

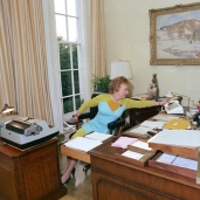

Spare a thought now for Rose Mary Woods, a footnote to history, and no doubt a woman of integrity and trust, Richard Nixon’s loyal secretary since 1951. In transcribing tapes, she discovers to her horror, so she said, the gap. She took the fall, for a few minutes’ worth, thinking that maybe she had

kept her foot on a pedal control while reaching for a phone call and mistakenly hitting the record button rather than the stop. This “Rose Mary Stretch” didn’t really convince anybody, and besides there’s another 14 minutes to account for.

There have been numerous dogged attempts to unearth what was there and what happened. A special investigative panel of forensic audio experts went at it at the time; they were able to find that there were actually between 5 and 9 segments to the buzz corresponding to different electrical outlets the recorder had been plugged into at various times, that it was done by hand, that speech had been there, but that despite trying a variety of highly specialized techniques they couldn’t recover it. Later investigations, as recently as 2009, have examined the tape as well as Haldeman’s somewhat suspicious handwritten notes from the meeting, which may or may not have been fiddled with. Hyperspectral imaging, video spectral comparison and electrostatic detection analysis were used, and the results? Bupkus. It’s a buzz, a few buzzes in fact, and at least for now, unexplained buzzes they will remain. Theories continue to abound—that Rose Mary Woods did more damage than she thought, that shadowy “White House lawyers” got to the tape, or, as Alexander Haig once suggested, that Nixon himself, through technological ineptitude, had a hand in it. Or there’s the simple explanation that when Elvis and the aliens showed up, their magnetic fields wiped the tapes.

And yet, there’s the tantalizing hope that some day, some new technique will come along, like fingerprints and DNA did for criminal investigations, that will let us hear beneath the buzzes and, finally, know. Because we do always want to know.

Thinking about the gap initially put me in mind of the famous piece by the pianist John Cage, called 4’33”, which consists of 3 movements of musicians doing nothing. Silence. Except it isn’t silence— Cage wanted listeners to focus on the sounds of the environment and fill the space from within. Like the gap, also not silence as I had originally thought, it’s a void, a hole, into which we can pour our doubts and suspicions, and perhaps hear what we want to hear.

That wanting to know was more than just strictly political in this case. The techniques that were used in the original forensic audio investigation broke new ground and became a textbook for future work, eventually forming part of the standards for verifying authenticity of tape recordings.

Demonstrating once again that much as we love a mystery, we’ll keep digging until we figure out a way to figure it out, and in the process sometimes push forward the boundaries of our knowledge.

References

Examination of H. R. Haldeman Notes.

http://www.archives.gov/research/investigations/watergate/haldeman-notes.html

Mellinger, Philip T. (2011). The Deep Throat Operation and the “18 1/2-Minute Gap.” Washingtonian. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonian.com/articles/print/2011/11/16/the- deep-throat-operation-and-the-18-minute-gap.php

Shenon, Philip. (2005, January 23). Rose Mary Woods, Nixon’s Secretary, Dies.

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/23/politics/23cnd-woods.html

The EOB Tape of June 20, 1972: Report on a Technical Investigation. (1974). Retrieved from http://www.aes.org/aeshc/docs/forensic.audio/watergate.tapes.report.pdf

“Watergate” and Forensic Audio Engineering.

http://www.aes.org/aeshc/docs/forensic.audio/watergate.tapes.introduction.html