“The Very Hungry Caterpillar,” “If You Give a Mouse a Cookie” and “Clifford the Big Red Dog” are just a few of the iconic picture books that have shaped childhoods for generations. The stories found in these pages teach their readers valuable lessons and play a critical role during early childhood development.

According to the National Children’s Book and Literacy Alliance, children need books to develop critical thinking skills, connect with characters and better understand themselves and the world around them.

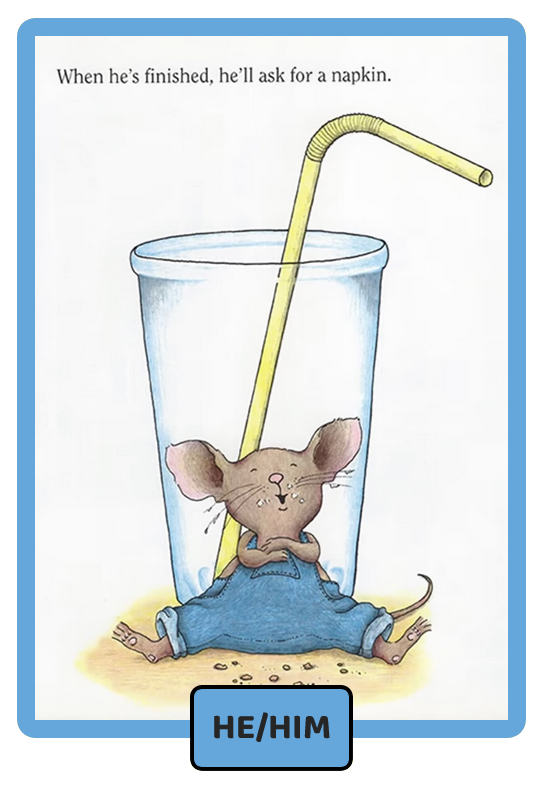

But digital humanities expert Melanie Walsh wanted to know, “Which animals do we gender and why?” In many of these beloved stories, animal characters are almost always reflexively assigned male pronouns, which raises questions about the messages children absorb while reading these books.

Walsh, an assistant professor at the UW Information School, analyzed hundreds of children's books and published her findings, “Bears Will Be Boys,” with “The Pudding,” a digital publication that explains ideas debated in pop culture with visual essays. Her team identified the most popular English-language children’s picture books that featured at least one anthropomorphized animal, reading about 300 books total. From there they noted the gender of each character that was important to the story.

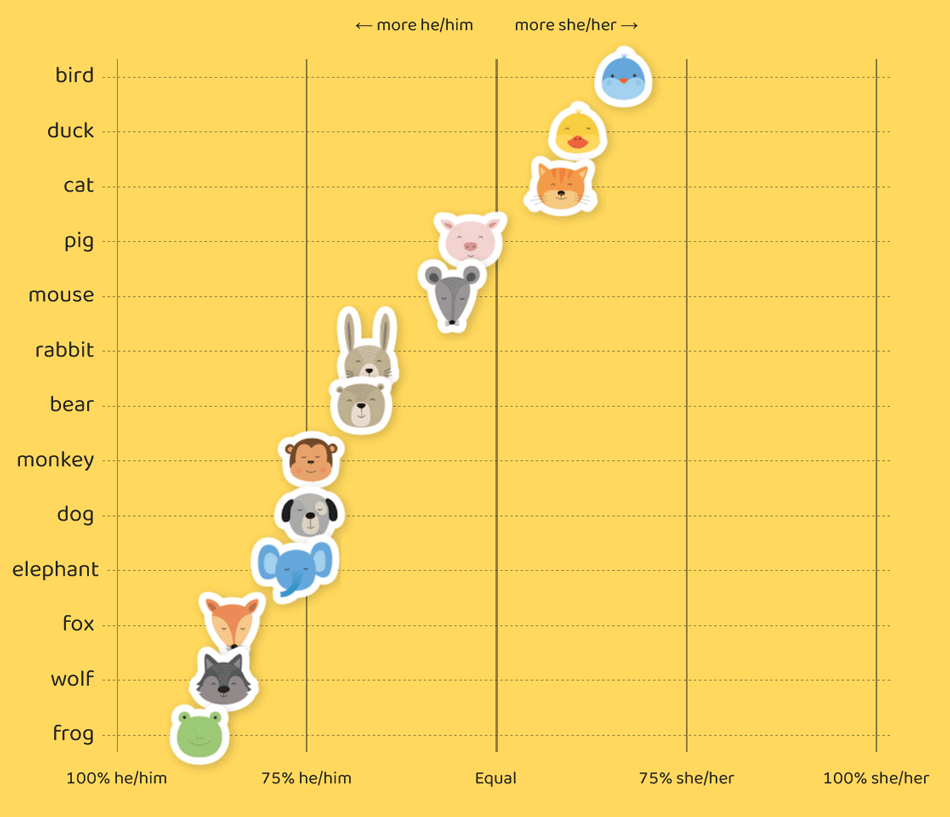

To avoid projecting their own presumptions, they only referenced texts with feminine (she/her), masculine (he/him) or neutral (it/they/them) pronouns. They found that male animal characters were twice as common as female ones. Animals like frogs, wolves, foxes, monkeys and bears tended to be male, while only birds, ducks and cats were found to be more consistently gendered females.

Building on their findings, Walsh and Pudding journalist Russell Samora also explored how readers instinctively gender animals when not given any labels. For example, in “But Not the Hippopotamus” by Sandra Boynton, a bear and a hare are depicted wearing bow ties, accessories that are traditionally considered masculine. Boynton, however, never gendered the animals in the text. Would readers identify them as boys?

The team surveyed 1,300 respondents to complete a story that began, “And then the bear said, ‘I must go to the river.’ Upon arriving …” Without telling the participants what the experiment was about, Walsh and Samora were able to observe whether readers assigned a gender to the animal. Other animals were swapped randomly for the bear, including bird, cat, pig, duck, mouse and dog.

Similar to what Walsh observed in published works, all animals tilted more male than female in the survey responses. While the majority of respondents identified as female, male pronouns appeared three times as often.

“I’m really proud of the work we did,” Walsh said.

Walsh collaborated with The Pudding’s team of graphic designers and journalists to translate the data into a user-friendly, visually engaging piece that includes graphs with drawings of the animals to identify where Walsh saw the patterns of male or female pronouns. The collaborators at The Pudding added that visual element to Walsh’s findings, transforming the plots into a visual story.

Walsh had been teaching The Pudding’s data essays in her classes for years, saying the stories are great for learning how to communicate with data.

“I usually have my students write a Pudding-style piece,” she said, “Now I can tell my students a little bit about what's happening behind the scenes.”

On social media, Walsh has heard from people sharing how her work has caused parents to think differently about the books they read to their kids, sparking an interesting conversation about the impact of gender in children’s books.

In a recent piece she wrote for Publishers Weekly, she went over her findings and how they reveal the bias humans reflect in animal characters. She noted that after the piece was published, many authors and parents reached out to discuss the findings.

“I've heard from a lot of illustrators and authors who have said either that they're going to think twice or think more deeply about the animal characters that they create and how they gender them,” she said.