Amy J. Ko received her introduction to computing when she first picked up a TI-82 graphing calculator in seventh grade. The University of Washington Information School professor was taking a pre-algebra class, and her teacher made the students input formulas into the devices.

“I thought that was the most boring thing in the world and I was not interested in it at all,” Ko recalls. “But, after class, one of my classmates showed me a version of Tetris that his older brother had gotten onto his TI-82.

“And I was interested in Tetris.”

She used a mail-order catalog to buy a cable to copy the Tetris program onto her TI-82. Unfortunately, the game was so slow that it was unplayable.

She pored over the manual trying to understand the TI-82 programming language. Doing so, she finally got Tetris to work fast enough so she could play.

“That was the moment where I felt like, ‘Look at this powerful medium that lets me make games, that lets me share things with other people, that lets me create art and express myself in all kinds of ways,’” Ko said.

Her desire to learn more about computer science was uneven throughout her high school years, however. A community student mentored her on some aspects of computing and a foreign exchange student from The Netherlands taught her variables.

“She really cares about computer science education and especially approaching it from an equity-focused lens.”

But in her senior year, Ko didn’t have a computer science teacher in her high school outside Portland, Oregon. Still, she took the Advanced Placement Computer Science exam. Testing conditions were less than ideal.

“I just walked in with no knowledge of what would be there, and I was the only person in the school that took it,” Ko said. “So, they locked me in a literal janitor’s closet and said, ‘We'll see you in three hours.’ And they plopped the paper exam down on a bucket and gave me a chair.”

Ko overcame that challenging start and even earned a 3, a passing score for AP exams, despite not knowing the test’s programming language.

Now she’s an accomplished academic, researcher and associate dean for academics for the iSchool. And she’s focused her career on improving computer education in the K-12 system.

“I don't want to generalize that experience to everybody's experience now, but I know that things like that continue to happen in most schools in the country today, even 25 to 30 years after I experienced them,” Ko said.

You’d be hard pressed to find someone more involved in shaping the efforts to expand computer education in Washington. Ko has lent her expertise to nonprofit groups such as Code.org and CS for All Washington; been a driving force for the opening of the UW Center for Learning, Computing and Imagination; and created new training techniques for computer science teachers.

“She just has this way of pushing forward and keeping the work moving forward,” said Anne Beitlers, who has worked with Ko at the UW’s College of Education. “I don't understand how she has the capacity to do that in the way that she does.”

She’s invaluable precisely because she’s involved in so many groups both formally and informally, said Terron Ishihara, the computer science program supervisor for the Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.

“She really cares about computer science education and especially approaching it from an equity-focused lens,” Ishihara said. “The fact that she has been doing this work for so long is pretty significant.

“She’s kind of the main cornerstone of the CS education community because she just has so much historical knowledge.”

Ko approaches this work in an altruistic manner that aims to invite others to the table.

“What really stands out to me about Amy is her ability to really bring people together and build community,” said Adrienne Gifford, a middle school teacher.

High demand for computing education

Washington, the birthplace of Microsoft and Amazon, faces challenges when it comes to computer education. Only half of public or tribal schools in the state even offer a computer science class.

There aren’t enough computer science teachers at the secondary level and those who do teach can often find more lucrative careers in private industry.

Computer science is usually looked at as a pathway to high-paying jobs in industry. And that’s important. A Brookings Institution study found that high school students who took a single high school computer science class see an 8% increase in their wages.

Hundreds of CEOs at some of America’s largest companies such as Microsoft, American Airlines and Uber this spring signed an open letter urging states to require computer science courses for graduation.

Ko sees a distinction between digital skills — such as turning on a computer and loading Microsoft Word or Google Docs — and computing skills. The latter involves asking broader questions about what information is, what computers are and what computers can do and can’t do.

“How do we make classrooms work for every kid?” Ko asks. “How do we make classrooms work for every teacher?”

While that may sound theoretical, these questions address very real issues today in both the classroom and the workplace. For instance, many youths and even many professionals are looking at generative artificial intelligence and wondering why they need to learn such things as language arts.

“That question is both at the heart of computing and at the heart of language arts,” Ko said. “It's getting in the way of being able to become great readers and great writers and it's getting in the way of becoming great scientists.”

One of her main concerns is the unequal access to computer science education, such as for students of color or students who live in rural areas.

“How do we make classrooms work for every kid?” Ko asks. “How do we make classrooms work for every teacher? Right now, we've got a lot of classrooms that work for some students, and we've got some pedagogies that work for some teachers, just not everyone.”

Nearly a decade ago, Ko approached the UW College of Education to speak about the importance of computer education with an impassioned plea for the college to educate computer science teachers.

“She said, ‘We need to do something about this. Would anybody like to work with me?’” said Beitlers, who is the director of the Secondary Teacher Education Program (STEP) at the UW. “And I raised my hand and said, ‘Yeah, I would.’”

Four years ago, they created an extra quarter of education as an add-on to STEP, the one-year master’s in teaching and certification program at the UW, for computer science.

To get the program off the ground, Ko and Beitlers applied for a National Science Foundation grant. When that grant ran out, Ko found private philanthropy to continue it.

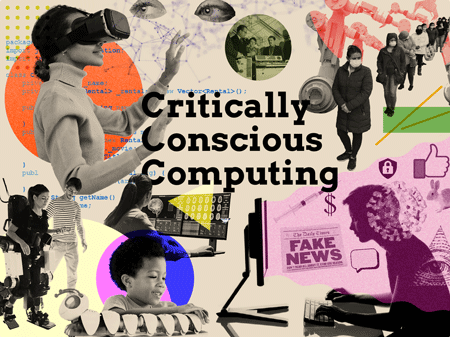

From this research, Ko has created and contributed to Critically Conscious Computing, a free, open-source book on teaching computer science. “She very, very quickly learned how to write really amazing curriculum,” Beitlers said.

'An amazing advocate'

One of the people who took the STEP computer science course was Gifford, who teaches middle school computer science at Open Windows School in Bellevue. Gifford and Ko have continued to collaborate on culturally relevant computer science education research in the two years since Gifford graduated from STEP CS.

“This relationship that we have built has definitely been one of the most supportive and generative professional relationships that I've had in my two decades of teaching,” Gifford said.

One of those efforts has been the creation of Wordplay, a coding platform that works with all of the world’s written languages.

“Most programming languages that are taught commonly in K-12 schools are really based on English, not just English syntax, like keywords, but also English semantics,” Gifford said.

This can be difficult for multilingual learners, she said. She did a survey of students in her computer science classes and found more than 60% speak a language other than English at home. “There's like 15 or 16 different languages spoken in my classroom,” she said.

Researchers at the UW Center for Learning, Computing and Imagination created and continue to develop Wordplay for use by students who don’t speak English their first language. Wordplay is being used in Gifford’s classroom with the idea of expanding its use to other classrooms in the future.

Outside of her role as an educator and researcher, Ko has been a persistent, passionate voice speaking in favor of computer education to policymakers.

Ko has helped increase funding and awareness and motivated legislation, said Tammie Schrader, a former teacher and now educational consultant who has worked with Ko.

“She is an amazing advocate for computer science,” Schrader said.

The two haven’t always agreed. Last year, a bill was proposed in the Washington Legislature to require computer science as a high school graduation requirement. Ko opposed it and mustered opposition to it because it was an unfunded mandate.

Schrader supported the bill, saying that money eventually would have been found. “If we wait for the perfect freaking bill to come out that serves every district, we will never move forward,” Schrader said. “It will never happen.”

Still, the lack of financial support is a source of frustration with budget cuts at the state level and a federal administration that appears skeptical about science and adversarial about equity efforts and higher education.

Ko estimates that it would cost $100 million a year to fully fund computer science courses and train computer science teachers in the state.

“Even if states want to do it — and I think our state very much does — finding $100 million a year to create that infrastructure to grow public education in that way is a hard political fight that not a lot of our state legislators are ready to fight,” Ko said.

Even with looming economic uncertainty, Ko is displaying leadership by focusing on “students as people and not just numbers on a spreadsheet,” OSPI’s Ishihara said.

“I would just highlight the humanness and the humanity that Amy brings,” Ishihara said. “For me personally, I've just always found her very calming to be around and that is a valuable trait to have when there is a lot of uncertainty around funding.”

Beyond being a product of the public school system and her own experiences in public schools, Ko has another reason to support secondary school education. She comes from a family of educators.

Her mom worked for more than 30 years as a fifth-grade teacher in Oregon. Her daughter just started in the profession as a special education teacher in San Diego. She says her family inspires her.

“So, when I thought about the things that I wanted to give back to, it was really about this particular profession,” Ko said. “Even though I wasn't going to be a teacher in K-12 of myself, I viewed my role as really making sure that all of the resources that teachers need would be there.”