The phone buzzed the same moment the email arrived last spring. Vikram Puri answered the call first.

Puri had landed a prized summer internship in software development at SanMar, an Issaquah-based company that is the largest supplier of wholesale imprintable clothing in the U.S.

Then, Puri opened the email from the Information School. He received his second — and final — rejection from the Informatics program, a major that he had set his heart on since arriving at the UW.

State Impact Report: Learn how Informatics and other Information School programs are making their mark on the state workforce.

• Web version

• Flipbook

• PDF download

“It was so bittersweet,” Puri said. “Knowing that I can’t apply again just leaves you defeated. Like you can’t do anything about it. I feel like getting an internship should be harder than getting into a major.”

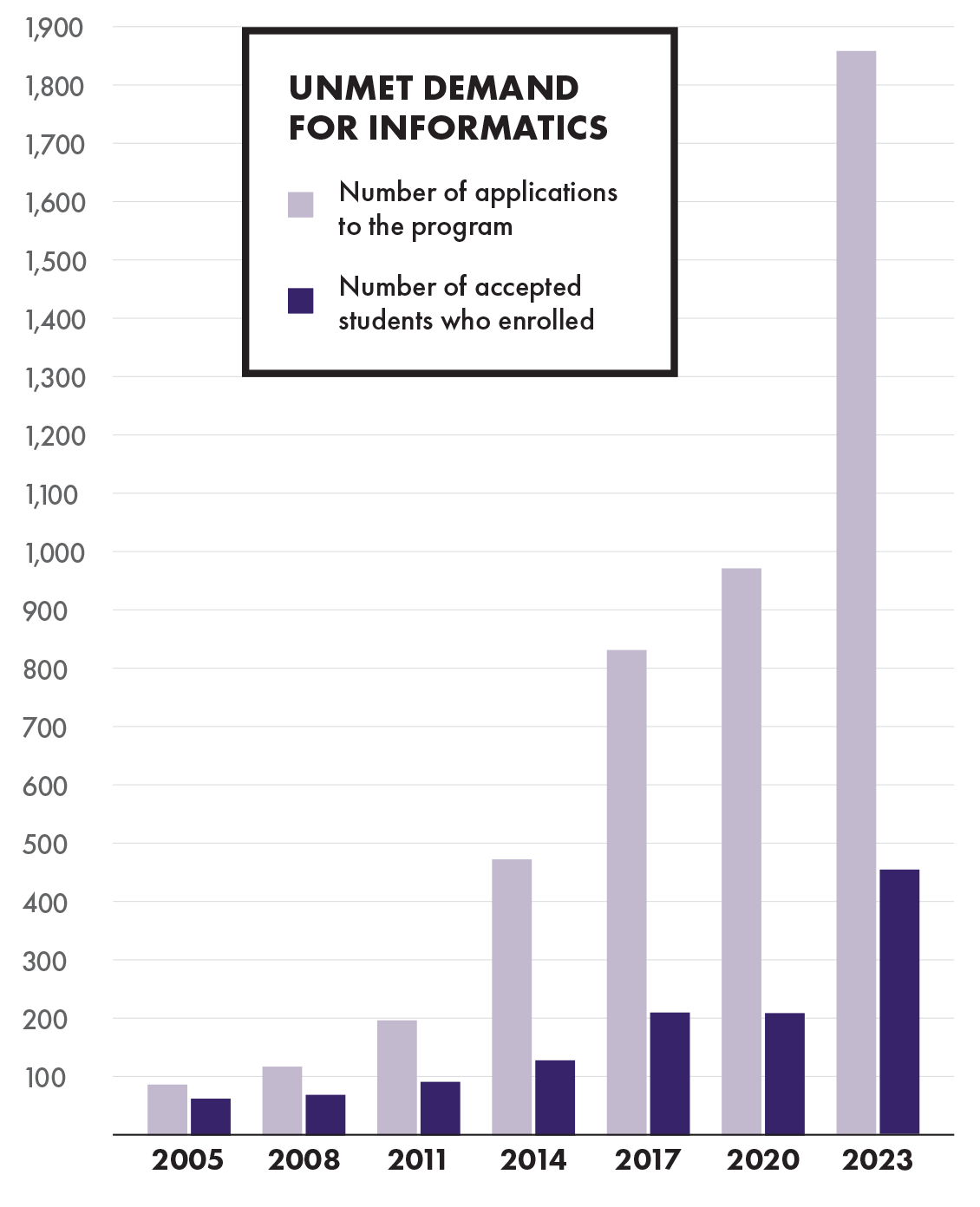

Informatics is one of the most competitive programs on campus. Fewer than one in three students who apply for the undergraduate program are accepted due to space limitations. Hundreds of students who would succeed in the program and later in their careers are left on the outside, leaving students as well as faculty frustrated.

In academic year 2023-24, the Informatics program received 680 applications from freshmen, or first-year direct to major, but was able to accept only 191 students, or 28 percent. The program also received 1,176 applications from current UW students as well as transfer students. Just 360 of those applications were accepted, or 30 percent.

Rayyan T. Cunningham was among the fortunate ones. She dropped out of high school in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, struggling to learn with the transition to online-only courses.

“I was only a sophomore,” Cunningham said. “I was like 15 years old. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, my world’s crashing.’ But I knew that I wanted to pursue higher education.”

She put herself back on track, heading to Renton Technical College to finish her high school equivalency diploma, then to Green River College in Kent for college prerequisites and finally to the UW in winter quarter 2023.

The stress had only begun. She spent months writing and rewriting her essay with hopes of getting into the Informatics program. She was accepted on her first attempt in fall 2023, but those months were filled with anxiety.

“I had to contain my excitement (about being at the UW) — I had to remind myself this isn’t it,” Cunningham said. “You’re still not in a major. It’s like you’re on a life raft, but it’s gonna deflate soon. You have to get on the real boat.”

Growing demand

Informatics is the study of inventing ways of combining technology, data and people to solve problems. There’s good reason why so many people want to enroll in the program.

Informatics is the study of inventing ways of combining technology, data and people to solve problems. There’s good reason why so many people want to enroll in the program.

People with an Informatics degree can pursue a host of in-demand careers, from software development to product management to cybersecurity. The tech industry employs nearly 360,000 people working directly for tech companies or in technology roles at other companies, according to the Computing Technology Industry Association (CompTIA).

The trade association expects Washington state to add more than 15,000 tech jobs this year, a 4.2 percent increase. The estimated salary for tech workers in Washington was $129,618 in 2022, 139 percent higher than the state median wage.

Demand is so high that Microsoft and Amazon both boosted salaries two years ago. Microsoft increased merit-based pay for employees and middle managers, while Amazon more than doubled the base cap for corporate and tech employees from $160,000 to $350,000, according to Geekwire. “I think students are right to see all of that demand in the labor market and to see all of those high salaries and to say, ‘Maybe I’ll do that,’” said Amy J. Ko, an iSchool professor, associate dean for academics and former Informatics chair.

It’s also an exciting time to work in the tech industry, especially as artificial intelligence reshapes everyday life, said Jaime Teevan, chief scientist and technical fellow at Microsoft. “AI is going to transform how we work, and people are going to shape the way AI evolves,” Teevan said. “The iSchool’s Informatics program is critical for companies like Microsoft. Now more than ever, tech companies are looking for graduates who can think like a scientist and build with humans at the center of technology.”

Jenny Abdo was in the first cohort of students in the Informatics program. She was casting about for a major when she read about Informatics in The Daily. She felt it would be a good fit. She’s now a senior leader at Amazon’s generative AI go-to-market program.

From her perspective, the iSchool offered both hands-on independent work and collaborative projects that build vital teamwork skills. “If you want to be a software developer, computer science is probably the right choice,” said Abdo, who earned a B.S. in 2002. “But there’s so many other career options that you just don’t know about or think about when you’re an undergrad that this could prepare students for. It’s helped to make me into a Swiss Army knife.”

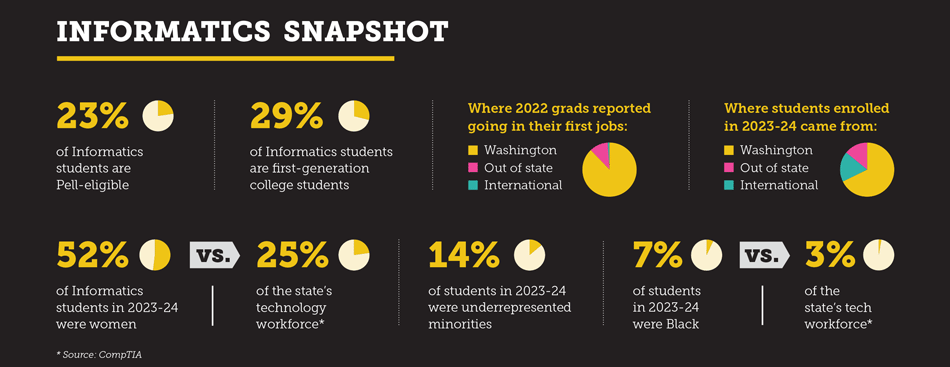

Washington’s six public universities aim to meet industry need. For instance, 88 percent of Informatics graduates went to their first job in Washington, while just 11 percent went out of state and 1 percent left for international jobs, according to an iSchool survey of 2022 graduates.

It’s not enough, Ko said. The Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering produces about 600 undergraduates each year, the iSchool about another 400, and programs at other institutions produce even fewer.

“Most of the people that are taking those jobs right now in our region are coming from elsewhere in the country and elsewhere in the world,” Ko said.

> Learn more about where Information School alumni are working in our State Impact Report.

Accepting responsibility

Informatics is among many majors at the UW that are “capacity-constrained,” meaning that admission is not guaranteed. Students must apply. The reason is the university doesn’t have either faculty or classroom space to handle demand.

When it was founded in 2000, the Informatics program accepted 35 students. In 2023, the program accepted 453 students. While that’s sizable growth, the number of people applying to the major has far outpaced the number of available seats. In the first year, 87 students applied, compared to 1,856 applicants last year, an increase of 2,033 percent.

The iSchool is the only school or college on campus that doesn’t have its own building. Instead, the iSchool’s 75 faculty members share office and classroom space in five buildings spread across campus, including in windowless basement offices of the forestry building and the UW Tower, a long walk from campus.

“It’s actually been a huge part of our retention challenges, too,” Ko said. “The faculty here feel like they just barely have the resources they need to survive in contrast to the elite schools.”

Ko helped build the model for growth for the Informatics program when she chaired the program from 2017-2023. She thinks the program has reached the limits of what it can do with its current resources.

“I think that answer is almost certainly a combination of state and industry support,” Ko said. “At the moment, neither of them have stood up and said that it is their responsibility.”

Musical chairs

The iSchool is doing its best to handle the overwhelming demand. Five years ago, the school started accepting direct-to-major students who are accepted as first-year students into the university and the major at the same time.

In the last year and a half, the iSchool instituted a policy to allow applicants only two attempts at getting into the Informatics program. Administrators found students were jeopardizing financial aid and academic careers when they repeatedly applied to the packed program.

Most of the students who apply to the iSchool are from Washington state. Last academic year, 53.2 percent of all iSchool enrolled students were Washington state residents. For the Informatics program, this rose to 67.8 percent.

Faculty members as well as student reviewers comb through the applications, reading all the essays, which are weighted more heavily than grades. The reviewers look for “concrete examples of why they want to be here and what they have done in their past and what they’re looking forward to in their future,” said Christine Noyes-Williams, the iSchool’s associate director of admissions.

“It’s draining to know that there are students who are well-qualified, who would succeed in your program, and you just you don’t have capacity,” Noyes-Williams said.

Admission has been so competitive that students seek any edge. The iSchool found that students, for instance, created a black market registering for Informatics prerequisite classes and then selling the spots for as much as $800 on Reddit, a violation of university policy.

A couple of well-known influencers — one a current student and another an alum — offer online tips and meetups to help with applying and writing essays.

“We have quite a few students who have entrepreneurial spirits, so I was not surprised at all to see them take a next-level approach,” Noyes-Williams said. “College prep coaches have existed for high-income families for years and years; I don’t see it as anything particularly different.”

Diverse workforce

It’s no secret that the technology industry tends to be white and male. The tech industry in Washington is even more so than the U.S. overall. Just one out of four Washington tech workers are women, while half of the overall workforce is women, according to CompTIA.

Just 3 percent of all tech workers in the state are Black and just 5 percent are Hispanic or Latino. Overall, the state’s workforce is 5 percent Black and 12 percent Latino.

The iSchool has made strides in narrowing this. Federal and state laws prevent the university from basing admission on race, gender, ethnicity or other demographic factors. But Noyes-Williams reviews demographic details after every admissions period to see how the current Informatics program measures against the state’s K-12 enrollment.

“What are we doing intentionally in outreach is to make them aware of the option and see themselves as UW students and as Informatics students,” Noyes-Williams said.

One of the iSchool’s big wins in the area occurred in the past year when the Informatics program reached gender parity. In 2023-24, the Informatics program had 52 percent female students compared to 39 percent five years ago.

And 6.7 percent of Informatics students are Black, double the percentage of the state’s current tech workforce and higher than the K-12 population of 4.6 percent. There are still areas for improvement. Hispanics or Latinos account for 25.2 percent of the state’s K-12 population, but just 3.7 percent of Informatics students.

There’s a problem with homogenous groups designing technology. They tend to design it for themselves.

“It is just very clear in research and in practice that people tend to solve the problems that they see,” Ko said. “And then it’s very hard for them to get them to solve the broad diversity of problems in the world.”

Heartbreaking decisions

Nijeer Parks spent 11 days in jail in New Jersey in 2021 for aggravated assault, unlawful possession of weapons, resisting arrest and other charges. He didn’t understand why until after he was released.

Parks, a Black man, was misidentified by facial recognition software. While this technology has become increasingly accurate, research shows that it is drastically prone to error when trying to match faces of darker-skinned people.

Cunningham pointed to this case as one the reasons she wants to get into the tech industry. She would like to bring a perspective of a woman of color to government policy around technology.

Since she joined the Informatics program, she’s also worked to help others get accepted into the program by reviewing prospective students’ essays prior to applying, posting tips on social media, as well as holding a position with the Women in Informatics student group, which hosts essay review sessions.

As she pursues her Bachelor of Science in Informatics, Cunningham calls it heartbreaking to see so many of her friends get rejected. “I understand the point of it being capacity-constrained,” she said. “We went to UW for a reason. This is what we signed up for, but I wish that the undergrad process had more equity within it.”

Puri, the student who received his final rejection from Informatics last spring, started at the UW in 2023 initially with the goal of attending the Allen School. Like Cunningham, he was a community college transfer, attending Bellevue College for a single year. He enjoyed software coding and knew he wanted to work in the tech industry.

But Puri learned about the iSchool from one of the social media influencers and fell in love with the school, pointing to the collaborative nature of the students and how everyone in the program was supportive. His parents wanted him to attend the Allen School, but once he showed them details on the Informatics program, they, too, were convinced.

When he was rejected the first time, he was with a group of iSchool students, and they comforted him. After his final rejection, Puri frets about what he wrote in his essay. He felt that he had a comfortable upbringing and didn’t want to be dishonest. Maybe he didn’t have enough stories of overcoming obstacles.

He still wants a job in the tech industry and is looking at options such as a statistics data science program. He doesn’t regret his time attempting to get into the iSchool.

“Every single person that I’ve met in Informatics tends to be extremely kind, extremely outgoing and just thoughtful and willing to help,” Puri said. “I wanted to be around these types of people who are willing to work together to raise everyone up.”