Sock wrangler Chelsie Fonseca does a little of everything at John’s Crazy Socks, an online retailer and social enterprise that features thousands of pairs of quirky socks. She packs the Happiness Gift Boxes and does the gift wrapping. She painted a mural with blue-and-yellow flowers — the colors associated with Down syndrome — in a bathroom at the company’s Long Island headquarters. She even took a turn modeling at a beauty, fashion and art show in October 2022, wearing a pair of the company’s Halloween-themed socks decorated with ghosts, bats and candy corn, along with a black lacy dress and “The Nightmare Before Christmas” T-shirt.

As an autistic person, Fonseca also speaks out on why employers should consider hiring disabled people. “I think it’s a wonderful idea to hire people with different abilities, because that gives us a chance to be out in the real world and experience different people and learn new things,” Fonseca said.

Her story — and the lessons learned from her employment — are helping autistic people obtain jobs across the country through a partnership with the University of Washington’s Information School.

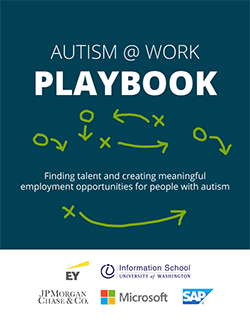

John’s Crazy Socks is a member of a collaborative group of companies across the country called the Neurodiversity @ Work Employer Roundtable. The effort was started in 2017 by major corporations Microsoft, SAP, JPMorgan Chase and EY.

Those Neurodiversity @ Work founding companies realized that hiring autistic people was not an area where they compete, so they decided to join together and share best practices. (The group was originally called Autism @ Work Employer Roundtable.)

The roundtable now includes about 60 companies, including some of the largest corporations in the U.S. such as IBM and Microsoft and smaller companies such as John’s Crazy Socks. Mark X. Cronin and his son John — who has Down syndrome — started the sock company in 2016. It now employs 34 people, 22 of whom have a differing ability; the most common diagnosis is autism.

All of these companies had different approaches and practices around hiring neurodivergent people, including autistic people. That’s why they turned to the iSchool to help identify and distill their best practices into a guidebook that would benefit organizations across several industries.

The Autism @ Work Playbook is a 61-page resource guide, part gospel and part roadmap for hiring autistic people. Hala Annabi, an iSchool associate professor whose work includes research on inclusive hiring practices, led the effort.

The Autism @ Work Playbook is a 61-page resource guide, part gospel and part roadmap for hiring autistic people. Hala Annabi, an iSchool associate professor whose work includes research on inclusive hiring practices, led the effort.

Microsoft has had a culture of inclusion from its earliest days and started its own autism hiring program in 2015, said Neil Barnett, director of hiring and accessibility at the company. He praised Annabi for her talent for working with separate companies to put together the playbook.

“She’s really good at taking the research, the insights and distilling it down into ‘commonspeak,’” Barnett said. “And presenting it in a way that anyone can digest and understand it. You almost have to translate that research into something that people can read and digest that makes sense to their work.”

Annabi realized the complexity of autism in the workplace during a study conducted six years ago. In the study, Annabi met an Asian-American autistic woman who led a product management team in a large technology firm.

The woman masked her autism, meaning that she didn’t reveal her diagnosis at her work or to her coworkers. Instead, she would brainstorm social topics to talk with her team members about and schedule those on her calendar.

“She had to code — using her own word — certain types of social and nurturing behaviors in her calendar,” Annabi said. “She’d say, ‘I just wish I could just get the work done and not worry about these other things.’”

Research suggests that only 15% to 20% of autistic people in the U.S. are employed, Annabi said. A study by Drexel University found that 42% of autistic people never worked for pay in their 20s.

The hiring process is biased toward people based on social characteristics, favoring extroverted behaviors, having little do with the job or the candidate’s skills and putting neurodivergent people at a disadvantage, Annabi said.

The Autism @ Work Playbook goes beyond getting people in the front door. The playbook makes the case for not only hiring neurodivergent people, but also supporting their growth and career development in their roles.

“It’s one thing to hire people in entry-level jobs, but how do you continue to help them in their career?” Annabi said. “This is true for all employees, but sometimes it becomes more challenging with neurodivergent people to see the pathways for themselves and to advocate for themselves for promotion.”

Organizations hire neurodivergent people for several important reasons. In addition to it being the right thing to do to provide equitable access to employment opportunities, many companies, especially over the past few years, have been trying to fill the talent gap, Annabi said. There aren’t enough people with skills needed in the workplace.

“It’s really hard to secure tech talent,” Annabi said. “So this was an untapped market. Especially earlier on, there was a great need for technology workers, data scientists, cybersecurity folks that firms like SAP and Microsoft need.”

Another reason is representation, and it’s not just checking a box. If you’re building a product for a mass market, particularly technology, you want to be able to make the design accessible to the broadest number of people possible. The best way to do that is to include neurodiverse individuals on your team.

“If you think about accessibility, there’s no better way to create accessible products at your company than having people with disabilities at the center,” Barnett said.

The playbook is one of the most vital resources in the field, said Tara Cunningham, CEO of Beyond Impact, a consultant group that helps companies remove barriers to recruitment, onboarding and retention with a focus on neurodiversity.

“It has the University of Washington name on it, which is really important,” said Cunningham, who was diagnosed as autistic later in life. “And then you have the original starters of the Autism @ Work inclusion movement. It gives validation to this document.”

She always shares the playbook with her clients who are seeking to develop autistic or neurodivergent programs. “I believe that it’ll be the full Fortune 1000 in the next five years,” Cunningham said.

Too often, companies chase what Cunningham calls “purple squirrels,” people with certain degrees or experience who just don’t exist. By broadening the search, these companies are able to find talent that may be overlooked. And it’s not just helping neurodiverse individuals, it’s helping others as well, Cunningham said.

“The idea is to create an environment that is less intimidating and more approachable for someone that either has anxiety or has perhaps a learning disability and needs a little bit more time to process and think through their answers.”

“We’re finding that if you create systems that are good for neurodiversity inclusion, it also helps disadvantaged communities and first-generation college graduates,” Cunningham said.

The playbook contains the distilled practical knowledge of pioneering companies that have tapped into the talents of neurodistinct individuals and provides a blueprint for companies to follow the same path, said Robert D. Austin, a professor of Information Systems at Ivey Business School and an affiliated faculty member at Harvard Medical School. Austin is a leading scholar in the emerging field of neurodiversity and employment.

“This is a big win for neurodistinct job candidates, their families, the companies that need talent, the governments that gain new taxpayers, and societies that become more fair and sustainable,” Austin said.

Annabi has been happy that so many companies have embraced the playbook and joined the roundtable. While this has changed the lives of thousands of people so far, millions more neurodivergent people could benefit. “So I think while we’ve made some progress, some really good progress,” she said. “I think we still have a long way to go.”

Currently, Annabi is developing a version of the playbook for the federal government in collaboration with the MITRE Corporation and the nonprofit Melwood to support neurodiversity employment across federal agencies.

One of the ways that the program will grow is by word of mouth through businesses or organizations such as Moji Coffee + More, a nonprofit with coffee shops in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

The nonprofit was started in 2019 with the help of a Special Olympics coach and a group of parents who were concerned about what support would be available to their children after high school graduation. Moji Coffee has a mission to provide meaningful employment to people with differing abilities and build up their job skills for the future. The two coffee shops now employ 27 people.

Moji program director Dan Wellman learned about the Autism @ Work Playbook when Microsoft’s Barnett spoke at a conference hosted by Moji last year. The Moji program director saw how the practices could benefit his organization.

He’s been impressed with the suggestions in the playbook for hiring and also for scaling the program to an organization. He’s shared the PDF file with other employers.

He’s changed some of his practices due to the resource guide, such as meeting a job candidate in a neighborhood park or going for a walk with an applicant before the interview begins.

“The idea is to create an environment that is less intimidating and more approachable for someone that either has anxiety or has perhaps a learning disability and needs a little bit more time to process and think through their answers,” Wellman said.

Mark and John Cronin, the father-and-son duo who started John’s Crazy Socks, frequently travel the country to talk about the experience.

Mark Cronin said he doesn’t talk about the moral decision to hire people who are seen as different from the norm, because that should be self-evident. Instead, he argues the business case. He boasts that his company, which has shipped more than 400,000 packages, has a better record than Amazon.

“We do better shipping than Amazon and John, he puts a thank you note and candy in every package,” Mark Cronin said. “Jeff Bezos is not doing that at Amazon.”

Employers have been looking for good workers for years now, Mark Cronin said. There are 20 million people with a disability who are ready, willing and able to work. He said that employers need to look beyond what these employees can’t do to what they can do.

“That person may not be able to get through the interview,” Mark Cronin said. “They may not look you right in the eye. They may not give you a firm handshake. What the heck does having a firm handshake have to do with writing good code?”