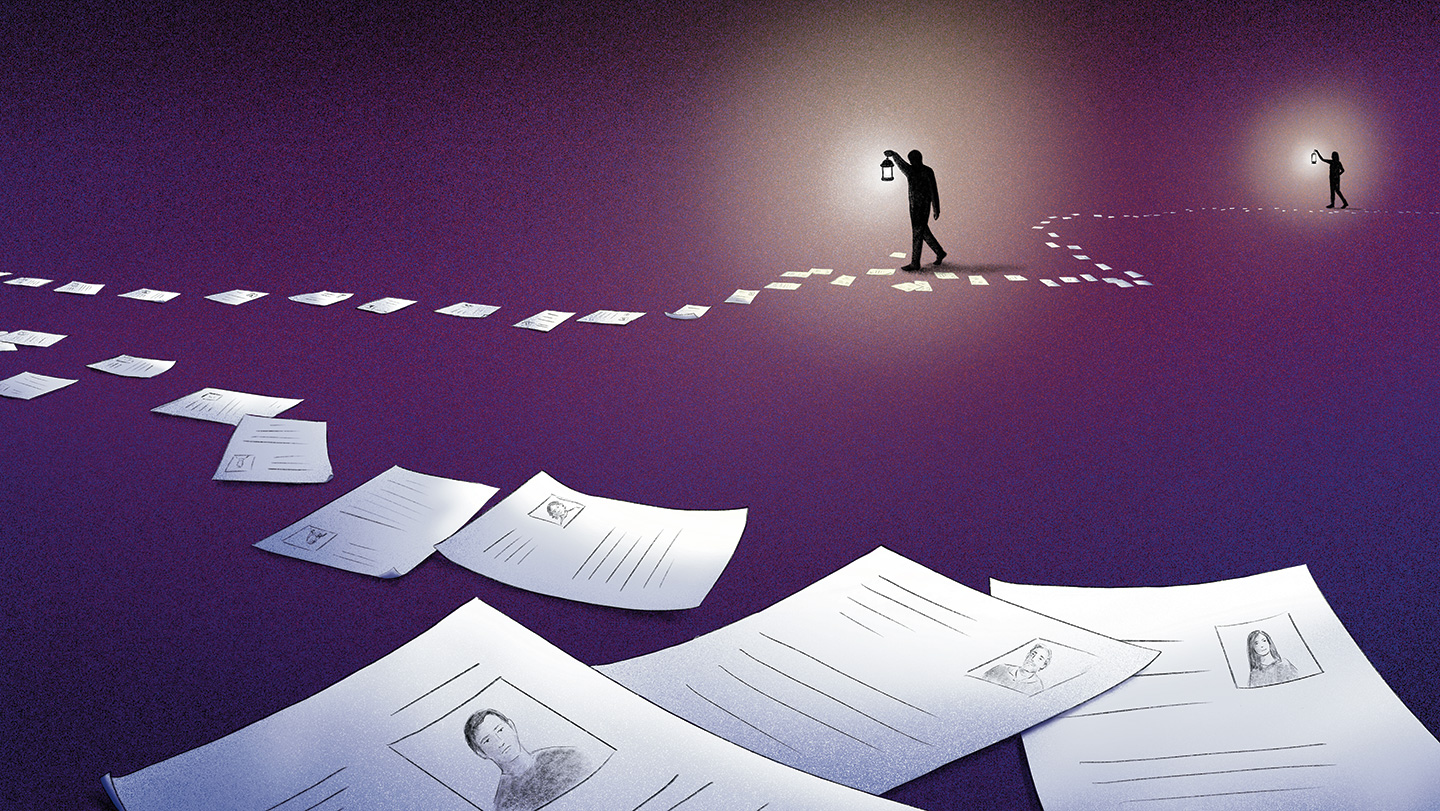

The evidence was there, buried in tens of thousands of pages of documents: Local law enforcement agencies were failing to comply with Washington state law protecting immigrant rights. To prove it, the University of Washington Center for Human Rights (UWCHR) needed to find the signal in the noise.

That was right in the wheelhouse of Information School faculty and students. Several of them were part of a campus-wide research collaboration that produced a recent report showing that, contrary to the law’s stated purpose, local police and jails remain a pipeline to immigration enforcement and deportation.

The rights of undocumented immigrants are supposed to be shielded under 2019’s Keep Washington Working law, which prohibits law enforcement agencies from detaining people based on their immigration status or sharing information about them with federal authorities unless required by a court order. In practice, the law has so far been applied inconsistently, the UWCHR report stated. While some local agencies have quickly adapted, others continue to alert federal agents when they encounter someone they suspect is undocumented. Information continues to flow passively, as well, through databases that are shared between local law enforcement and agencies such as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement or U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

After receiving anecdotal reports of deportations originating from routine interactions such as traffic stops, the UWCHR requested thousands of emails and arrest records under the Freedom of Information Act. Researchers dug into the records in 13 of the state’s 39 counties to see if they could detect patterns of practices that circumvent the law, UWCHR Director Angelina Godoy said. Even in limiting their research to those counties, they faced a massive undertaking.

“We immediately realized the research was important, but the question was, how do you do research on such a broad scope?” Godoy said.

iSchool researchers, led by Associate Professor Ricardo Gomez, brought their ideas to the project about how to parse the data that the UWCHR was able to pull from the records. Once they cleaned up and organized the text, they analyzed it for trends. They looked at who was seeking information from whom, who was sharing information with whom, and the mechanisms for information sharing between local officials and immigration officials.

“There’s a lot of noise, there’s a lot of repetition, there’s a lot of redundancy, and it’s not necessarily in any particular order,” Gomez said. “So you need an information management process to deal with the large volume of information to make any meaning of it.”

“There is abundant evidence of continuing collaboration between local law enforcement and immigration enforcement.”

What they found was sometimes surprisingly brazen disregard for the law, Gomez said. Some sheriffs in rural counties have even stated their unwillingness to comply.

“There is abundant evidence of continuing collaboration between local law enforcement and immigration enforcement,” he said. “It’s amazing that there is such a strong paper trail left behind in emails. I’m sure now that the report is published, agencies will say they are changing their policies, but it’s also possible they will continue to collaborate and hide their tracks better.”

iSchool doctoral student Yubing Tian focused her work on Grant County, doing a deep dive into more than 8,000 pages of emails and several hundred arrest records. Tian said she was surprised by how often local officials would proactively refer people to immigration authorities, sharing personal information in a way that the law now forbids.

“We found multiple instances where a local official would say, ‘Hey I came across this person. You should look into them. Here’s their date of birth and screen shots from the Department of Licensing database,'” Tian said.

Gomez’s and Tian’s work was part of a broad effort involving community partners with the UWCHR’s Immigrant Rights Observatory and faculty and students from across the university, including the center’s project coordinator, Phil Neff; the School of Law; the Department of Sociology; UW Bothell; the Department of Law, Societies & Justice; and the Jackson School of International Studies. iSchool faculty members Bob Boiko, Marika Cifor and Megan Finn consulted on the project, and doctoral student Ana Bennett helped analyze email and arrest records. Numerous iSchool Master of Library and Information Science students participated in analyzing the data and looking for trends, earning credit in Gomez’s course on information and social justice.

“It’s a valuable learning opportunity for them to do social justice work with an information angle, to apply information science skills and library science skills to real-world problems that further and support social justice,” Gomez said.

Despite gaps in compliance, the report notes that Washington has made progress in its efforts to support the rights of undocumented immigrants. Many county agencies immediately changed their policies and several agencies have taken corrective measures after learning they had staff who weren’t following the law. Researchers will continue to monitor and defend the rights of the estimated 240,000 undocumented immigrants in Washington, Godoy said.

“Hopefully a year or two after the law has passed, we’d start to see more institutionalization of compliance,” she said. “We’re excited to do more research and see if the trend lines of that first report continue.”