For Lindah Kotut, it sounded like a fine excuse for tea. Traveling to a conference in Namibia in southern Africa in 2019, Kotut wondered what people who aren’t online think about the online world. So, she decided to ask them.

Kotut, who was pursuing a Ph.D. in computer science at Virginia Tech, arranged to interview village elders in Namibia and her home country of Kenya who had never used a computer.

Turns out, they do have strong opinions about their privacy and security online, about how they’re represented and how their stories are told in the digital world.

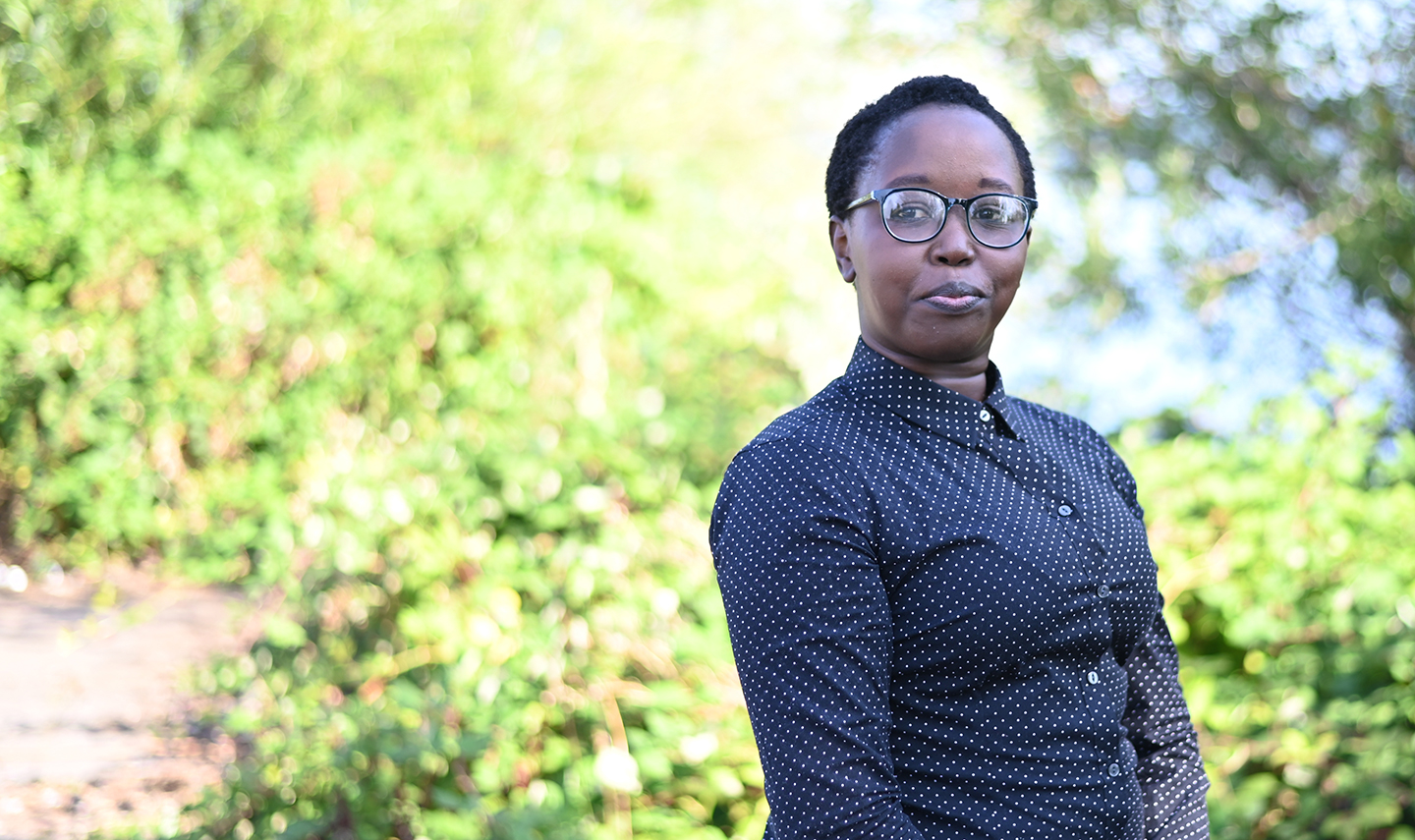

This became a life-changing moment for Kotut, who made her dissertation about this tension between the online and offline worlds. The new assistant professor at the University of Washington Information School thinks that this should be a priority for people pushing the frontiers of computer science.

“When you build the next system, it should become almost a default question to ask, ‘Who have you talked to about this?’” Kotut said. “How is it affecting people outside of your circle? How is it affecting someone who doesn't have power?”

Her academic adviser at Virginia Tech, Scott McCrickard, noted how she looked at Kenyan museums and how they capture and share stories compared with villages and their oral traditions.

“She explored the comfort levels of the elders there with regard to what is it that they're OK with sharing and what is it that will go to the grave with them,” said McCrickard, an associate professor of computer science.

Kotut’s interest in computer science began when she was growing up in Kenya. Her father had a subscription to Reader’s Digest and the stories that interested her the most were about computers, memorably ones where computer scientists worked with astronomers on the Hubble Space Telescope.

The high school that Kotut attended in Kenya had computers, but they were used for little more than typing class. Kotut remembers vividly the first time that she got on to the internet.

In 2006, she walked into a cybercafe curious about this thing she had heard about: Google. She was told it was a place where she could type in any question and get an answer. So, she typed in, “What is Google?”

“You have to establish trust, but the best way to establish trust is to work with people who already work with these communities.”

After high school, Kotut decided to study abroad for the opportunity to learn computer science. She passed on Finland (too much snow) and Japan (she wanted to work on computers, not spend time on the Japanese language requirement). She decided upon the U.S. and landed a partial cross-country scholarship at a community college in Albany, Georgia.

She later obtained a bachelor’s degree from Georgia Southern University, a master’s degree from Norfolk State University and her Ph.D. this past May in computer science from Virginia Tech. She proved a quality teacher, McCrickard said.

“She has mentored master's students and, toward the end, other Ph.D. students,” McCrickard said. “I think her real joy comes in mentoring undergrads and getting them involved in the research process.”

During her academic career, Kotut became interested in cybersecurity and privacy and about how people interact with technology. At Norfolk State, Kotut built a program that helped people determine how their smartphones were using personal data.

Everybody who used the program offered glowing comments, but they stopped using it after a couple of days. That made Kotut realize that even the best technology is useless if it isn’t used.

She came to the same conclusion about cybersecurity. It doesn’t matter how effective a security system is if people aren’t turning it on.

“It's like building the most secure fortress in the world and then leaving the door wide open,” Kotut said. “What's the point of doing that?”

After interviewing people in Namibia and Kenya, Kotut was supposed to go back for more research, but the COVID-19 pandemic forced her to scrap those plans. Still, the work made her interested in pursuing research about the digital world and oral story traditions, especially in Indigenous communities.

That’s why she was so attracted to the iSchool, which has a research focus on Indigenous Knowledge and an experienced cadre of faculty with a mission to study the use of digital technologies to protect and preserve the stories of Native communities.

“You have to establish trust, but the best way to establish trust is to work with people who already work with these communities,” Kotut said.

Kotut wants to meet with the Indigenous populations in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere around the world while exploring how technology affects those without a voice in it.

“That vision is what I'm bringing into the start of my career,” Kotut said. “It's been an adventure so far. I'm just looking forward to see what happens.”