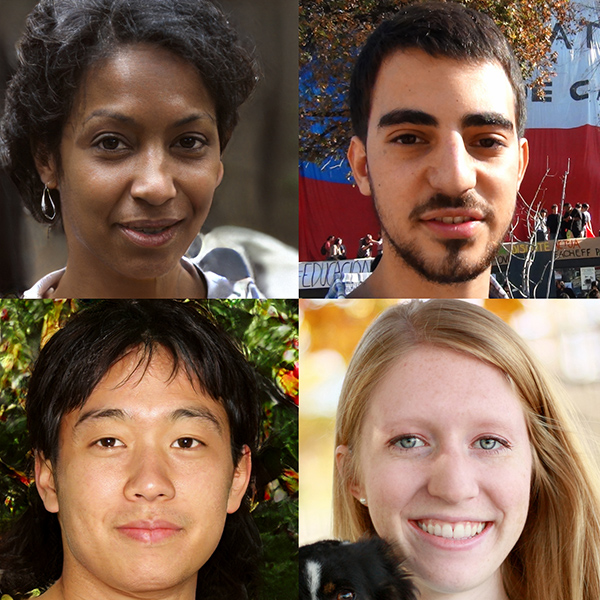

Go ahead, give it a try. Look closely, study the context and click your answer, choosing which of two realistic headshots is actually a real photograph — and which is complete fakery.

How did you do? Don’t worry — read the site, and try again.

Whichfaceisreal.com is the new website from Jevin West of the University of Washington Information School and Carl Bergstrom of the biology department, the duo who drew wide attention since 2017 for their innovative Information School class, “Calling Bullshit in the Age of Big Data.”

As with their Calling BS class, Bergstrom and West seek to address — and help people navigate — the increasing amount of misinformation and deception they see online. When the two saw the artificial intelligence-powered website Thispersondoesnotexist.com — which renders extremely realistic portraits of utterly nonexistent people — they wanted to spread the word that the ability to generate believable, lifelike faces was now possible and proliferating online.

“We did not create the technology,” Bergstrom stressed. “We wanted to get the word out that this is now possible. Generally up to this point, we have trusted faces in photos: If it’s a photo, it’s a real person — at least up to this point.”

As Bergstrom and West explain on WhichFaceisReal, the “phenomenal” algorithm used to create realistic fake faces was developed by software engineers at NVIDIA Corporation and uses what is called a General Adversarial Network, where two neural networks “play a game of cat and mouse,” each trying to create artificial images and the other trying to tell the difference. “The two networks train one another,” they write. “After a few weeks, the image-creating network can produce images like the fakes on this website.”

And as with their Calling BS work, the website was immediately popular, with about 4 million “plays” of the game in about two weeks.

Are people guessing well? Mostly, yes, West said. Overall, so far, about 70 percent of players choose correctly when trying to distinguish fake from real — and the site may be helping them learn to do better.

“In our initial analysis this appears to be the case, but we need to verify this with more rigorous analysis,” West said. “We’re also looking into what kinds of images are the most difficult to discern. For example, are fake images of younger or older people more difficult to identify?”

There are a few hints and “tells,” however, that help one choose more wisely. Bergstrom and West offer advice in a tab on their site labeled “learn.” Look for inconsistencies in the background of the photo, or how the hair or eyeglasses are rendered.

And there is what they call the “silver bullet” to know fakes online: The algorithm used, called StyleGAN, is unable to generate multiple fake images from different perspectives of the same faux-person. So their advice is, to verify, look for a second photo of the same person.

Or as Bergstrom said, “How do you know if your next Tinder match is real? See if he has a nice headshot as well as a nice shot of himself petting a tiger. Always look for that tiger photo.”

West and Bergstrom plan to continue adding features to their site to add to the challenge of choosing between real and fake — they may remove backgrounds (which are among the “tells”) to make the choice harder, and will be asking users to view a single photo and say whether it’s real or generated.

“We want to bring public awareness to this technology,” said West. “Just like when people started to realize that you could Photoshop images, we want the public to know that AI can replicate human faces.

“That will hopefully make people start to question things they see in different ways. It will hopefully force us all to corroborate evidence even when we see a photo that looks human.”

###

For more information, contact West at jevinw@uw.edu or Bergstrom at cbergst@uw.edu.