Rosetta Stone, BCE

From plain stone to venerated symbol of ingenuity, this is truly a rock of the ages.

Transcript

If you had something really important you wanted to record, and you wanted it to last for a while, how would you do it? Well, that depends on how important it was, and how long you were thinking. The longer the term, the sturdier you’d want your medium to be. We don’t have that much experience with digital media so we don’t quite know how durable those are, not to mention will there still be a device around that can read it; it doesn’t matter if a Zip drive or 8 track tape is still OK if there’s nothing to stick it in. We do have really old documents on vellum or parchment, both made from animal skin which is harder to get at Office Depot, and even older ones in baked clay but that’s just tedious.

If you’re seriously in it for the long haul, though, it’s hard to do better than stone. Stone lasts. It can be worn away by weather or pollution or be damaged, yes, but...stone lasts. A message for the ages deserves a medium for the ages, though sometimes the medium can outlast the message. That’s the case for one of the most famous messages in the world, which I bet you would instantly recognize and I also bet you have no idea what it says, or why, or about whom which tells us something about durability as well as the various twists and turns a document can take.

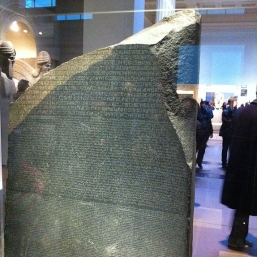

A fragment of a stela, engraved with what is called the Decree of Memphis in 3 languages, now known as the Rosetta Stone.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School. Now this is a document; just shy of 9 square feet, about 1700 pounds, and about 2200 years old. The basic story of the Rosetta Stone is well known, an ancient record, written in three languages, and how, 20+ years later, those multiple versions of the same text led to cracking the code of Egyptian hieroglyphics and thus an entrée into their long-forgotten civilization. All quite familiar, yet as is so often the case, there’s more to the story. For instance, Jean-Francois Champollion, the teacher who eventually cracked the code, never saw the real thing. Each version was for a different audience: hieroglyphics for tradition’s sake (that language had been dead for centuries and only a few priests could even read it), demotic for your run of the mill literate Egyptian, and Greek for the Macedonians who had actually been in charge for the last century or so. There’s really 4 languages on it, including “Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801” and “Presented by King George III,” neither entirely true, helpfully painted on the sides—yesterday’s vandalism is today’s historical detail. And for many decades, it’s been the most popular, and most lucratively marketed, object in the British Museum.

Even less well known is what it says, and why it was created. It’s a verbose decree to shore up and reinforce the rule of the pharaoh Ptolemy V. Imagine you’re a boy king, succeeding to the throne aged five after both of your parents are murdered by a conspiracy featuring your father’s mistress, who then rule as your regents as you grow up before they got lynched by a mob in a revolt. Nine years later, you’re in a tenuous position in a time fraught with peril, dissension and upheaval. If you knew what was good for you, you’d lower taxes, too, free political prisoners and kiss up to the temple priests, after polishing off some rebel leaders by impaling them on the stake. In return, the priests proclaim your legitimacy and greatness, add your birthday to the holiday list, erect statues, etc etc etc. And put up stelae all over the place to announce this glorious decision; this is all lovingly recorded in what we now know as the Rosetta Stone. It was likely originally leaned upright against a wall outside a temple, where it probably sat for several centuries until about 1/3 of the top was hacked off at some point, likely when it was reused as a building stone for a fort, near Rashid, or Rosetta, hence the modern name.

It’s been in the British Museum, object number EA 24, since 1802, apart from underground storage during wartime, and a nervy month’s loan in France in 1972 for the 150th anniversary of the decoding when some thought the French might try to keep it. It was so heavy an extension had to be built with reinforced floors to support it. At some point, chalk was imbedded in the lettering to make it more readable and wax added to protect it from grubby fingers (eek); it wound up so dark it was misclassified as black basalt until it was cleaned and revealed to be much lighter granodiorite. And--they intend to keep it.

This thing was created in the age of Hannibal and Cato, the Punic Wars, and the expansion of Rome, just after the Great Wall of China and the Terracotta Army, as the Mayas are starting to write and the Olmecs have come and gone. The Egyptians who erected it had every reason to believe the stone would stand forever; their society had already lasted over 3000 years. So when the decree ends by saying it will stand “alongside the state of the kind who lives forever,” they’re not kidding.

Many sources, historians and Egyptologists, wax eloquent about the Stone (always capitalized) as a gateway to the past, an emblem of discovery and rediscovery, a symbol of our desire to know and understand, and as part of the telling of history as much if not more than as a historical object itself. Granted. Museum folks focus on the provenance, tapping into the larger matter of ownership of cultural objects, so much an issue in recent years as more nations and peoples request—or demand—repatriation of things so casually appropriated in days gone by.

For me, though, as an information scientist, the most fascinating bit is this object’s journey as a document. It begins as a rock, and happily remains that way for untold gazillions of years before it’s quarried up near Aswan, sailed down the Nile and then shaped and carved with markings that meant something to the people who put them there. (More or less; the spelling errors in the Greek section mean the carvers either weren’t paying attention or didn’t understand it.) Then it’s put up outside temples to be seen and remembered, at least by the people who could read one of its scripts, otherwise it’s squiggles. Then Ptolemy V dies, is succeeded by his infant son, time passes, and the purpose for the decree faded, though the Stone remained, a bit like an old Presidential proclamation that means little to us today. After a couple of centuries, the dynasty falls, eventually the civilization and language and culture follow suit and it’s made into building material. Still carved, still meaningful...sort of, but underground and unseen for maybe a millennium. Dug up by the French, who lost it to the English, who plunked it in the British Museum, and many people studied the squiggles again, trying to make sense of them until they figured it out. It’s one of the great document stories of all time, which might account for some of its popular fascination.

The Stone was intended, and made, to last. It didn’t go quite as planned, though, surviving more by accident than design, and its original intent has long since been superseded by its role as a key to unlocking ancient long-forgotten Egyptian writing, language, and culture. Today? You’re listening to this podcast via some streaming process, and I use a cloud server to store my research and materials. We take digital information media for granted for its ease and convenience, though in terms of endurance, the antithesis of the Stone. If there are museums in 2000 years, what object from our time will occupy a similar place in a glass case and in the popular imagination? And where—and what—will the Rosetta Stone be on its journey then?

Parkinson, R. B., & British Museum. (2005). The Rosetta Stone. London: British Museum Press. Ray, J. D. (2007). The Rosetta Stone and the rebirth of ancient Egypt. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

References

University Press. Rosetta Stone. (2013, August 31). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Rosetta_Stone&oldid=571002455 Solé, R., Valbelle, D., & Rendall, S. (2002). The Rosetta stone. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows.