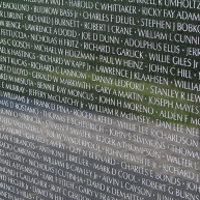

Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 1982

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is, clearly, a document, straightforwardly recording names and sequence; it also memorializes the war in general, our experience of it, and our coming to terms with it.

Transcript

How do you remember something? I’ve found that the string around the finger isn’t only cliché, it’s also unhelpful and potentially cuts off your circulation. I’m an inveterate note maker, lists, post-its, scraps everywhere; I’ve also been known to put things in the wrong pocket to jog my memory, and my friend Diane taught me the trick of throwing a book from the nightstand when something occurs to me just when dropping off to sleep, effective assuming you can recall why there’s a book in the middle of the bedroom floor in the morning.

Remembrances of a person are often easier: photographs, mementos, letters, diaries, there’s a wide range of objects of all kinds that help to evoke memories good, bad, and indifferent. Often these are private, or shared among family or a few friends. At times, though, circumstances dictate larger, broader, collective rememberings, and untold numbers of memorials of all shapes and sizes have been erected over the millennia. One of these, of an unconventional and originally contentious design, tried to capture the complexity of a decades-long conflict of decades in a simple, stark, elegant and ultimately beautiful way and along the way showed us more about ourselves and how we remember than anyone would have imagined.

I’m Joe Janes of the University of Washington Information School, and any story of the Vietnam memorial has to begin with Jan Scruggs, a volunteer infantry colonel who was wounded and saw 12 men die in a mortar accident. An alcohol-fueled flashback of that incident, 10 years later while watching The Deer Hunter, inspired him to envision a memorial to the men who died in Vietnam, one that would symbolize national reconciliation for a war that had riven the country, take no government money, and be, for those who served, their “delayed victory parade.” No small order, particularly when, after the first splashy news conference, exactly $144.50 had come in. That embarrassment fueled him and his organization, which maneuvered the twists and turns of official Washington, bureaucracy, doubt, scorn, and eventually marshaled the resources to build a monument on the National Mall, often called the nation’s front yard, nearly in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. But what should it be? After extensive discussion and rigmarole, a call went out for a competition in 1980, seeking a design that would “recognize and honor those who served and died” and acknowledge their “courage, sacrifice and devotion to duty. [It] will make no political statement regarding the war or its conduct. It will transcend those issues. The hope is that the creation of the Memorial will begin a healing process.”

It didn’t quite work out that way, at least at first. 1421 entries came in, anonymously, with names in sealed envelopes taped on the back. An expert jury, which included no veterans, cut them to 232, then 39, then 3. Their unanimous choice was #1026, engendering comments on its simplicity, eloquence, power, challenge, experience, reflectiveness, and reverence. The one-page submission depicted the memorial as “a rift in the earth”; later, it would be called a “black gash of shame,” but that lay in the future. We all now know envelope #1026 held the name of Maya Ying Lin, a Yale architecture student who entered as a class project—for which she received a B.

In an essay she wrote at the time but didn’t publish for nearly 20 years, Lin comes through as naïve on the ways of politics though fierce in defense of her artistic vision. She said she designed it for herself, what she believed it should be, not to second-guess the jury. Exploring the nature of memorials and their functions, she notes that until World War I, individual lives, and names, were rarely dealt with; a war memorial at Yale was being updated at the time with names from Vietnam and that process struck her, the power of a name, let alone more than 50,000. She traveled to Washington to see the site and had the “impulse to cut into the earth…opening it up, an initial violence and pain that in time would heal.” Her initial sketch seemed too simple, she thought, so she tried adding elements, but less turned out to be more, and her original vision, incorporating chronological names, became her submission.

After she won, the trouble began. Her Asian heritage, the black color of the wall, its simplicity, the lack of a heroic statue, all were criticized and worse. It’s hard to read accounts of the multiple controversies and near-deaths of the project, fueled by many quarters including original supporter Ross Perot and the odious Interior Secretary James Watt, without a smug hindsight. Yes, eventually a statue was added, as was a memorial to women who served and a plaque honoring those who died other than in combat, but today we know it would be built, and embraced, even in the face of such intense scrutiny and even hatred.

It is, formally, a list, of 58,272 names, from a database of “combat zone casualties” based on criteria from a 1965 executive order, in chronological order by date of casualty or date reported missing. Those missing are designated with plus signs, which can be converted to the diamonds next to the dead when their deaths are confirmed, or encircled if they come back alive, though none have as yet. 229 names have been added as of 2011, as the list is updated; no civilians are listed, nor are those who died from indirect causes, such as cancer from Agent Orange exposure, or suicide from post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s estimated those names would require two additional Walls.

The names are engraved in black granite from India (neither Canadian nor Swedish granite was deemed acceptable, as they had shielded draft evaders), in the Optima typeface. The sequence begins with 1959 at the top of panel 1E, the first on the East arm, and continues to its end 246 feet away, then loops back to the extreme western end with names from May 25, 1968, concluding at the bottom of panel 70W with men killed during the Mayaguez incident in 1975. All names are indexed by panel and line number and can be searched online. Getting everything right is a tough process, and it’s not perfect. The first two men listed, Dale Buis and Chester Ovnand, were killed by guerillas while watching a movie; Ovnand’s name was one of a few dozen misspelled (as Ovnard), because of conflicting records, and was eventually fixed and relocated; Sgt. Richard Fitzgibbon, Jr. was murdered by another airman in June 1956 and after years of lobbying was added in 1999 to panel 52E.

The memorial was dedicated on November 13, 1982 at the end of a weeklong tribute to Vietnam veterans, weeks after EPCOT Center opened and the Tylenol murders, and 2 weeks before Thriller was released. Almost immediately and simultaneously, two extraordinary phenomena surfaced: visitors reached out to touch the names, and eventually to make rubbings of them as a memento, as one would of a headstone. Then there were the offerings, which actually began, if the story is to be believed, with a naval officer who threw his brother’s Purple Heart medal into the trench where the concrete was being poured during construction. Tens of thousands of objects of all kinds have been left; flowers are not preserved, flags without messages are given to scouting groups, drugs are confiscated, but everything else is kept and preserved by the Museum and Archaeological Regional Storage Facility in Maryland. Many come without explanation or names attached, so we are left to wonder. They all mean something to somebody, though without context or purpose, they’re adrift in our collective consciousness.

If you’ve been to the Wall, you know – you’re immediately struck by the surface, black and polished. You can see yourself, surrounded by, reflected in, the dead and the missing. Name after name, row after row, panel after panel. We see ourselves as we see them. The Memorial is, clearly, a document, straightforwardly recording names and sequence; it also memorializes the war in general, our experience of it, and our coming to terms with it. You could also argue that each offering is also a document, though often uncertain, unknown, private, even secret, of a person, an act, a relationship, a regret.

I would go further. I would say that all of it, together, the totality of the wall, the additions, the tortuous processes, the objects individually and collectively: that, all of it, is the document. When you think of a war memorial, you think of marble columns, bronze men in heroic poses on bronze horses, or at least you used to. A memorial speaks, too, about its society and context when it’s built, and as it evolves over time; it’s as much about the remembering as the remembered. The story told here isn’t grand or exalted, not about generals or victory, it’s about people and of a war and a time not all that long ago that still requires healing, and reconciliation, and remembrance, one name at a time.