Cheryl Metoyer made her mark as a leading figure in tribal libraries and museums. At the University of Washington Information School, she established the study of American Indian knowledge systems as a prime focus for scholarship. Above all her accomplishments, she takes the most pride in the people she has mentored along the way.

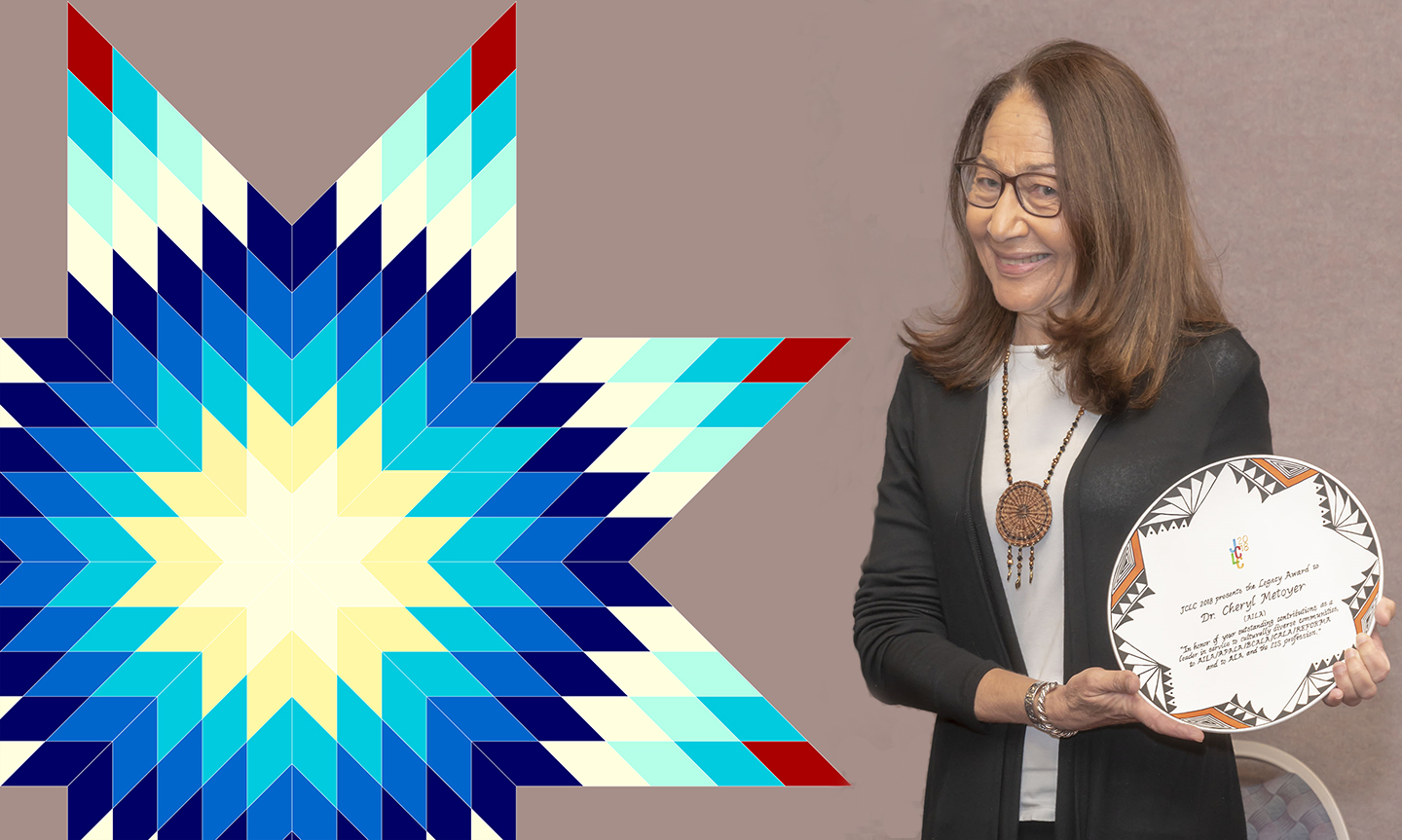

It’s that legacy the American Indian Library Association recognized with its 2018 Legacy Award at the Joint Conference of Librarians of Color in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In bestowing the honor, the AILA noted Metoyer's contributions to librarianship; assistance to American Indian libraries, museums and archives; and her mentorship of the next generation of Native librarians and educators.

Metoyer (Eastern Band Cherokee), instilled in her students the values of community, of acknowledging past injustices and studying and preserving Native American knowledge.

“What I hope they learn is the work of service and the service of work — that the work is about service to the community,” said Metoyer, now an associate professor emerita at the iSchool. “That is the critical piece. It’s very important that we be other-centered in our work.”

Metoyer learned that lesson first-hand while working on her doctoral dissertation in library and information science in the 1970s. As she conducted research at the Akwesasne Library and Cultural Center on the Mohawk Reservation in New York, she learned that the first requirement for meaningful tribal library services was the active involvement of the community. At Akwesasne the tribal leadership, library staff and community members all played a pivotal role in the design and mission of the library, she said.

“The tribal members worked together and graciously found the time to also include me in the whole experience,” she said. “I became very much a part of the families in the time I was there – feasting, canoeing, walking and laughing. It was wonderful.”

When she completed her doctoral dissertation, the library used her data to support its successful request for increased funding. For Metoyer, the experience helped develop her passion for tribal libraries. It also served her well when, in the 1990s, she was given a librarian’s dream job.

"The amazing thing about Cheryl is her mentorship never stops. It’s not strictly limited to her professional capacity."

— Miranda Belarde-Lewis

As director of information resources at the Mashantucket Pequot Nation Museum and Research Center in Connecticut, she helped develop two research libraries, the tribal archives and a museum. She was able to plan and implement everything she had learned at Akwesasne about how to build a library if you have the resources.

“The opportunity at Mashantucket was unprecedented. We’re talking about 300,000 square feet. It was wonderful,” Metoyer said. “We brought together the right group of people and gave them the financial resources to build the buildings, the collections and the services with the common mission of education — not only for the tribal members themselves, but for anyone seeking accurate information about the tribes within and beyond Connecticut.”

Those experiences provided a foundation for Metoyer when, later in her career, she was drawn back to the academy. After spending the late-1990s on the faculty at UCLA and the University of California-Riverside, she was lured to the UW iSchool by its first dean, Michael Eisenberg.

“Mike said to come and the students would follow,” she said. “It was a time when I felt the imperative to work with the next generation of Native scholars. I came and the students followed. And under the leadership of Harry Bruce, the next dean, our work flourished.”

Over the years, she has been the faculty advisor for six Native doctoral students at the iSchool and mentored several other graduate and undergraduate students. Importantly to Metoyer, each of her students has graduated. Two — Miranda Belarde-Lewis and Marisa Duarte — have gone on to faculty appointments themselves, and both credit Metoyer for inspiring them in their academic careers.

“The amazing thing about Cheryl is her mentorship never stops. It’s not strictly limited to her professional capacity,” said Belarde-Lewis, now an assistant professor at the UW iSchool. “I think she needs to get more awards. She needs to be recognized as a pioneer in the field and someone generally invested in the success of her mentees.”

Belarde-Lewis, a member of both the Corn Clan in Zuni Pueblo and the Takdeintaan Clan of the Tlingit Nation, said that if not for Metoyer, she likely would be on a different career path.

“Coming from museums, I didn’t consider a career in the academy,” she said. “I felt like I needed to work. Cheryl assured me that the activism and advocacy doesn’t go away and that I would still be working to help people.”

Duarte, now a professor of justice and sociotechnical change at the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University, said, “Dr. Metoyer’s leadership, mentorship, candor, and spirit of generosity changed my life.”

"I know of no scholar who has delved more deeply into understanding the close relationship between the human spirit, the story, the rights of American Indians, and the transformative practice of librarianship."

— Marisa Duarte

“I think of her as a mentor for a lifetime. I know of no scholar who has delved more deeply into understanding the close relationship between the human spirit, the story, the rights of American Indians, and the transformative practice of librarianship.”

Duarte, a member of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, said that when her credibility as a scientist and a scholar has been challenged on occasion due to her status as an American Indian woman, she has drawn from what she has learned from working under Metoyer.

“I think of Dr. Metoyer and how she effects sweeping social change on a local scale: by laughing at the irony of our tribulations, by embracing an internal spiritual bedrock, by developing a sharp rhetoric of compassionate dissent, by applying the healing power of time, and by believing in the inherent goodness of human beings, even when some humans make shocking moral miscalculations,” Duarte said.

As a professor emerita, Metoyer is still actively engaged in the iSchool community – advising on the school’s Native North American Indigenous Knowledge focus area; recruiting Native students to the iSchool’s programs; and continuing to mentor Belarde-Lewis and iSchool Assistant Professor Clarita Lefthand-Begay, along with the others she’s influenced in her career. Seeing her proteges succeed is what brings her the greatest joy.

“I can hardly contain myself when I listen to them deliver papers at conferences or present their work here at our iSchool,” Metoyer said. “I think, this is so good. My Native students — now graduates — are committed, well prepared and thoughtful. I’m very proud of them, and I share the credit with our tribal communities and my iSchool colleagues. In my view, the iSchool leadership, faculty and staff all contributed to their exceptional success. I am most grateful.”